by Samuel Hux (June 2022)

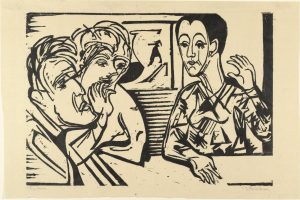

Conversation (Unterhaltung), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1929

Many years ago, actually rather early in my academic career, I realized that the only aspect of Teaching that I did not hate was teaching. Not a nonsense sentence. I mean that the only part of the occupation of a college or university professor I did not despise took place in the classroom or occasionally in conferences in my office. I was usually bored stiff with committee work and departmental meetings. I dreaded having to read (except for very few) and grade (all) student papers and exams. The only two things I really loved were (1) teaching, sitting or standing, scratching my head in thought, smoking a cigar or pipe when that was allowed back in ancient times, talking to and with the students about this idea or that book; and (2) having coffee or a meal while chatting with certain colleagues. I remember fantasizing, and telling a fellow faculty member, that although I would miss the classroom I would gladly give the whole thing up if I could have a paid job writing on whatever popped into my mind at the moment without worrying where it all was going eventually. Sounds, he said, like you’d have a series, not even a sequence, of digressions. That colleague is no longer with us. But that fantasy is still with me.

Two of my favorite books are Elias Canetti’s The Tongue Set Free, and Blaise Pascal’s Thoughts (Pensées). The first is ostensibly a volume of Canetti’s autobiography, but it is just as much, and remembered as, an interrupted series of thoughts on this and that and t’other matter: it could easily deserve the title Pascal gave his book. And Pascal’s is what it is called: one pensée after another, but not necessarily “after” in a sequential sense. They may be numbered, but not in the sense that 1-2-3-4-5-etc. makes sense. What comes to mind, as Pascal is thinking, appears in the series, and although Pascal was a mathematician as well as philosopher-theologian, he does not consistently think 1-2-3, but thinks as a man controlled by vital curiosity. It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that both Canetti and Pascal are essentially “digressionists.” But I digress …

***

What do they have in common—Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean Wahl, Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Miguel de Unamuno, Nikolai Berdyaev, Hazel Barnes, etc. (and a young Samuel Hux)? Existentialism. Whether that or Existentialisme, Existentialismus, Existencialismo or Existenz Philosophie. Some would add Soren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche and more. Although it seems to me a hell of a long way from Kierkegaard to Heidegger. (The Dane would turn over in his grave.) I arrogantly include my young self in the list above because I wrote a doctoral dissertation on the subject (a text best forgotten). Even then I struggled to see what they had in common, nothing like what thinkers called Marxist have in common. And why “Existentialism”?

By the way, I just remembered something from at least four decades ago. I had published an essay in which I took Norman Mailer to task for a misapplication of Sartre’s philosophy. Soon after that there was a piece in the New York Times Sunday Magazine by a critic named Benjamin DeMott on Mailer and some others; he quoted or paraphrased me (I forget which) identifying me as “a European Existentialist.” This amused some of my colleagues. But I digress; back to what I was saying …

What philosophy or theology worth listening to does not have something to say of Existence? Why not call Christianity and Judaism Existentialist? After all, they insist on the greatest existence of all: the existence of God. Is it because the existence we are talking about here is human existence? Then call Anthropology an existentialist discipline. And while you’re at it add History and Social Sciences and Etcetera. So why should a specific philosophical point of view be called existentialist? In my reading I found only one convincing justification.

I can’t recall whether I first saw this in Being and Nothingness or the essay “Existentialism is a Humanism”: the Sartrean doctrine “Existence precedes Essence.” We first exist before we create our own developing essence through the choices we make. In other words, we do not have a personal nature (essence) at birth; we make who we are. Okay, so far. But Sartre is suggesting that we cannot at birth have a human nature because there is no such thing as a universal human nature, the radical aspect of Existence Precedes Essence—an idea few people are going to accept, including other “Existentialists”. and may be one reason leading Existentialists—such as for example Camus and Heidegger—dismissed the broad assumption that they were Existentialists. So be it, but at least Sartre has a coherent and distinguishing reason for calling himself by the disputed term. Good for him.

But on another hand, there is a “bad for him.” The most attractive thing about “Existence Precedes Essence” is the insistence that we choose who we essentially are or are becoming—which obviously puts a premium on choice, on the freedom of the will. Again, okay so far. But the Sartre of Being and Nothingness and “Existentialism is a Humanism” will by stages become Sartre the neo-Marxist and Sartre the Marxist, committing a kind of intellectual suicide it has always seemed to me. For Marxism has a contradiction at its very core: While it is a call to social and political action, which assumes we can choose to act, it is also a creed which “knows” the shape of the future which social and political action will bring about because Marxism is a determinism at its soul.

***

There are those who think there is no essential contradiction between Free Will and Determinism. William James was not one of them: “The Dilemma of Determinism.” Nor am I as I agree with my better (and one of my heroes). Determinism reigns in the natural physical world where natural laws govern events. The Earth will orbit the Sun. Given sufficient moisture above rain will fall. If you foolishly step off a roof you will fall. But you can choose not to step off the roof. A physical law called Gravity made your physical body fall. When you step off you have made a suicidal choice, or perhaps you are curious to see if the law of gravity is real, or perhaps you simply misjudged how close you were to the edge. But there is no physical law which says that your suicidal thoughts or your curiosity or misjudgment of distances were deterministically “governed.” Although there are some damned fools who would say just that.

The damned fools may claim to be philosophers, but they tend to be just sloppy thinkers or quite often fifth-rate social scientists. And their problem is that they cannot or will not realize the distinction between something being caused by and something being influenced or limited by. If you step off the roof having misjudged the distance to the edge, that event was not caused (deterministically) by your failure to have your vision checked; it was only influenced by that carelessness. Imagine someone arguing that British and French troops at Dunkirk could not possibly have been rescued had conditions been different, had there not have been sufficient Naval and civilian vessels available, and thinking that the surprising availability therefore caused the success of the operation, just as an unavailability of vessels would have caused a failure. What muddled thinking. The availability of vessels made the success possible; an unavailability would have limited the possibility. But the rescue happened because, within the limitations and extensions of possibility, the British authorities from top to bottom chose to make the effort. It is a major philosophical error to think that since possibilities are limited by circumstances determinism rules in the world of moral choice; the freedom of the will rules there.

William James makes a fine distinction. The determinist, invading the world of human actions instead of sticking to the world of physics and such, says that in every instance of a human action there is only one possibility, the possibility that is actualized. While the truth is that in every human action there are more than one possibility, so that “possibilities may be in excess of actualities.” So the determinist who does not stick to the proper realm of the physical laws of nature thinks that what I did yesterday at noon was the only thing I could have done, is telling me that when I chose to order a burger I had to “choose” it and free choice is an illusion, I can explain to him, the determinist, that the laws of physics and biology govern what René Descartes called res extensa, that which has weight and can be measured, but not res cogitans, that which is not physical, such as emotions, ideas, choices, none of which can be weighed or measured, can only be felt, thought, or chosen.

The concept of determinism implies “has to be,” that is inevitability. But if he says to me “You are wrong to believe in free choice, the freedom of the will,” I can say to him, probably without his getting it, “Did you have to say that to me, was your saying that to me inevitable? What caused you to say that to me other than your choice to do so?” For there is a basic dishonesty at the core of determinism-in-human-affairs. When the determinist tells you that you had to say or think such-and-such, he does not mean that he had to tell you that. Maybe dishonesty is not the right word. Maybe it’s achieved (chosen) stupidity.

***

Determinism and inevitability are inevitably connected. Given the law of gravity, if you fall from that roof you will plunge, no question about it. But “The Inevitable” has a religious ring to it, associated with a possibly unsolvable problem for theology, or Christian theology at least.

If, or since, God is omnipotent, infallible, and especially omniscient, He the Lord (not even a rad-fem will say She the Lady) is possessed of Divine Fore-Knowledge. That is, He knows not only the past and present but the future as well. Since infallible, what He sees through his fore-knowledge must happen. Otherwise He’s wrong and thus not all-powerful and all-knowing and therefore not God. It’s all there in Saint Augustine’s City of God and elsewhere. Consequently, as the omniscient God sees what you will do, you have to do it. Therefore, you may think you chose to do it, but instead you had to do it. So Freedom of the Will falls by the wayside and the determinist if he hears the news applauds.

But there’s a problem here. All orthodox Christians will believe God is omniscient, yet all will believe the sinner is accountable for his sins. Even the orthodox Calvinist who follows Saint Paul’s teaching that Faith alone and not Good Works gain you salvation agrees that you are accountable for your Works, good or bad. And accountability makes no sense unless your actions are the results of your free choices: it seems to make no sense if you are accountable for what you had to do since God foresaw you would do it. There’s a conflict at the heart of Christian theology, and I’m not here to resolve it.

Maybe the happiest Christians are those who worship, habitually, in those denominations that do not linger too deeply or at all on theological controversy. Pardon the digression.

***

There is a short way out for the determinist if he is philosophically sophisticated enough, which probably most often is not the case. There is a “problem” in philosophy called “The Mind-Body Problem.” It goes like this:

How does the Mind, which is a non-physical thing—call it for emphasis a spiritual whatever—effect changes or motions in the Body, which obviously is a physical thing? For instance, how can I if my back itches either wait for it to stop or make my arm reach awkwardly to my back and scratch until the itch is no more? How can the non-physical Mind govern the physical Body? So far this is a problematical question that seems to be unanswerable. And it is a duo-directional affair. The physical itching does not make me reach and scratch because I can wait the itch out if I so choose.

The determinist, if he is clever enough, could argue, “See, there can be action across the divide you have called in Cartesian lingo the res extensa vs. the res cogitans,” and let it go at that. Or he could take another tack. As some philosophers do.

Call it not the Mind-Body Problem, but the “Body-Body-Problem,” which as far as I can tell no one has actually uttered. Nonetheless, there are those who argue that there is no Mind, but rather a Brain; that is to say that Mind is merely a rather “mental” name for Brain. The important thing here is that the Brain, an extended thing (meaning it occupies space) that’s weighable and measurable, a hunk of meat in your head, is a part of the Body. And if that’s the case—or as the determinist could say, since that’s the case—it is subject to the physical laws of nature just as is the rest of the Body or any extended thing. The determinist now is practically crowing: See! Your brain is a physical thing. It has no free will! He’ll have no answer to my answer: Don’t be so proud of yourself. By your own lights you had to crow, could have done nothing else at that moment.

But, in Descartes’ view, the Mind is a separate entity from the Brain. You can’t say where it is, for it’s not a res extensa, occupies no space, but controls the brain as its instrument. I imagine it, in spite of doubtful logic, hovering over the brain. Or in a Cartesian metaphor—remember it’s only a metaphor—the Mind is like the captain in his ship, choosing how to use and where to sail his ship, but obviously not a part of or synonymous with the ship. Accept the Mind-Body-Problem as the wonderful mystery that it is.

Unless we are smart-ass social scientists (I could name a few) eager to shock the bourgeoisie with our intellectual guts, we know intuitively that we are endowed with the capacity to make free choices, within the limitations imposed by circumstance, and evolve ideas within the same. Ask yourself, do you really believe the brain, that piece of meat, can write poetry, compose music, paint a picture, or do philosophy; you know damn well, intuitively, those activities belong to the non-physical or spiritual Mind. Or let us be more fanciful for a moment. William James’s friend and colleague Charles Sanders Peirce once said in his intellectually brave but hilarious way, that the most successful planets are those which develop the habit of gravity. No mere brain alone could invent such a wonderful and loony tune!

I cannot leave determinism alone quite yet, because a classroom memory just leapt into my mind, not into my brain. Fifteen minutes or so of utter confusion as a student and I were talking at cross-purposes. Determinism as noun is clear enough, but the verb to determine is problematic. The student was wondering how he could be determined to improve himself if he had no free will to choose to do so. Good question. The answer of course is that if one says, for instance, “I am determined to solve this problem,” this is a matter of determination, not related at all to determinism. And if one says, for example, “It has been determined that the population is growing,” been determined has nothing to do with either the –ation or the –ism. This of course is not really a philosophical problem, but a linguistic one. But it has occurred to me more than a few times how occasionally difficult it is to do philosophy in a language as weird as English is, often as weird as it is lovely.

Weird? Let me count the ways. I can’t. Sometimes English has too many words, sometimes too few. I am told I am a fairly articulate person. But I often can’t find a necessary word and think there isn’t one. And of course, there may be too many words in English; count the pages in an excellent English dictionary, and then try French, Spanish, German, and so on. Think of bear for a moment. Are you thinking of an animal? Or of bearing the weight of an English word-book. We are told that bear has two different meanings, but the truth is that we have two totally different words which happen to be spelled the same way

And spelling! Why should the word should not be “shood” instead of looking as if pronounced “shoold,’ while its rhyming companion sounds as if made of wood? I am amazed that foreigners learn English, learn to pronounce a word they’ve seen in print, or to write a word they’ve only heard. There are too many examples of this phenomenon. Take the fourth word of the previous sentence. Many, which looks as if it should be pronounced “mayny” is pronounced “menny” or “minny.” I think it was George Bernard Shaw who made up the non-existent word “Ghoti” which might be pronounced “fish.” Gh pronounced f as in rough, o pronounced i as in women, ti pronounced sh as in nation. Of course this is a joke, but not nonsense. Why shouldn’t rough be “ruff,” women be “wimmen,’ and nation be “nayshun”? Shaw would have in his ideal linguistic world an English spelled just as it is pronounced—the spelling-pronunciation clarity which usually characterizes other European tongues. But that is equally as problematic. For instance, democracy and democrat are clearly related. Would they be so obvious were they “demockrisy” and “demuhkrat”?

In spite of the likes of Shakespeare and Keats and Yeats and more, English can be an annoying language. But not as annoying as some of its users. There’s a novel by Richard Russo (the title escapes me) in which a professor is nicknamed “Orshy” because whenever someone speaking in general fashion says “he,” Orshy will corrected him with “or she.” Before I switched to the Philosophy Department I labored for several years in English Department hell, as all English profs must, in English Composition, where one of the greatest crimes was to use the masculine He as a general third person pronoun. Which can cause many (or “menny”) absurdities. Of course if you’re talking about Fred you’ll say “He” and if about Frida “She.” But there are bi-gender names, so to speak, such as Marion or Jackie or Evelyn or surprisingly even Joyce or Shirley (anyone remember the great sports writer Shirley Povich?). So I can imagine a sentence such as, “I am told that Marion Smith lives in Boston, where he or she practices law.” More practically, I can imagine a sentence such as, “When you hire a lawyer you hope he or she is a good one,” because if you “hope he is a good one” you are a criminal. You didn’t used to be, back in the day when “He” was sometimes masculine and sometimes indefinite. How did my mother’s generation survive such humiliation? I used to tell my students that since we have He, She, and It, when they did not know whether the subject was male, female, or a dog, to use the construction He-She-It pronounced “He-shit.” Of course some supposedly educated people will use They, Them, or Their as a third person singular pronoun to avoid the offensive He, Him, or His in order to sound “with it,” while only sounding like idiots: “The student hopes their professor next semester will make their lectures more interesting.”

English was comfortable for centuries with He as indefinite pronoun for easily understandable reasons if you know anything about the history of the language. In Old English or Anglo-Saxon “He” was He (with a flat line above the e which my computer cannot do), while “She” was the masculine-looking Heo. He and Heo are so close that it’s no surprise that the common and shared letters, H and e, would become the indefinite pronoun long enough to be thought normal. The feminist certainty that this has been all a masculine conspiracy all along is nothing but mass paranoia.

Speaking of English Comp, as I was when referring to the English Department hell, it is a self-imposed hell … and as destructive as Hell. No one should be allowed in college who cannot write competently in his (or her!) own language. But they are, and the English Department is there to insist on Composition 101 plus. And 101 may be followed by one or two others. When a college requires a course it’s either a content course or a how-to course. If it’s a content course, then yes of course I approve of Philosophy or History or Etcetera 101 as there are certain subjects all students should be introduced to. But if it is a how-to course like 101 and 102 and perhaps 103 as well, the college is saying there are some methods of communication no one can master without expert instruction and then more instruction and maybe more because it—like composition in English—is so extraordinarily difficult and beyond normal human competence. And that is a lie. If one can speak coherently although not gracefully, one can gracelessly write clearly. The grace may come or may not, for style is somethin’ y’ got or y’ aint got, but is not necessary for clear communication anyway. If one does not have competent grammar in the native tongue after 12 years of public or private education it is hopeless to think he-she’s gonna get it now. Maybe cruel to say, but there are plenty of necessary ditches to be dug. In my academic utopia then there’d be no Eng Comp except for very bright foreign students competent in their own native languages, just as there are French or Spanish or German or Etcetera 101 for native English speakers.

My father did not complete high school, economic necessities intervening. His occupation took him away from home for several months each year, so there was a lot of letter writing. He wrote a lovely and vivid prose; I still cherish the memory of it. But as I was about to say …

Since it is not clear in every case whether a word is noun or verb, a construct for instance and to construct, German has the nice habit of printing each noun with a capital first letter. English did that until it dropped the habit sometime after the 18th century, for no good reason I can think of, printers’ convenience not a good reason. Change for change’s sake? Sometimes I would like to do what Bill Buckley wanted to do: Stand in the path of History shouting “Stop!” Some habits should have no time limit.

***

Speaking of habit; once a good thing, it has in recent years become an unpopular word. As if habits must be bad … or at best leaden and un-adventurous. Jake smokes too damned much, and Janet habitually does the same damned thing every day. If I tell you that James has a habit of opening doors for women whether it’s necessary or not, you might not think that’s a good thing to do, the ethical gesture dismissible because “habitual.” And feminist doctrine, so to speak, comes close to dismissing it as condescending, implying that females need the old-fashioned manners of the age of male domination, while females now need nothing from guys except their getting the hell out of the way. Feminist doctrine (or FemDoc) has no place for the recognition that James, possibly, is so gallant because he thinks, “This is the way I would want my mother Jennifer treated, and I know that if I acted otherwise she would turn over in her grave.” (By the way, I don’t have a habit of inventing characters whose names begin with J. I only or just wanted to make the examples sort of rhyme.)

I would call James’s habit an ethical one. But some habits are compulsive in a rather comical way. In one of David Sedaris’s books he has an autobiographical essay about his teenage behavior. (I can’t name it because I can’t find it, part of my library having been flooded.) As I recall, he must touch every telephone pole he passes. I seem to recall one scene that seems too ridiculous to be accurate, but I think it went like this: climbing the stairs at home, he must lick each carpeted step. To insure luck? After a brief ownership of a klinker which had trouble starting, I close my eyes to make sure my car ignition catches. So far it works. But the motivation behind some habits is hard to fathom.

Chuck, a pal of mine in grad school lived across the street from Professor Beck, chair of the Poli Sci department, who always parked his car with front bumper aligned with a telephone pole in front of his house. Chuck and I were drinking beer in his apartment, celebrating Thursday, a celebratory festival invented by Chuck. Chuck looked at his watch, said “Watch me”, exited the building and drove his car across the street and parked in front of Beck’s house with his rear bumper invading Beck’s habitual parking space by a foot or so, and returned to await the Professor’s arrival. Within a few minutes Beck arrived and parked behind Chuck’s invading car, sat for maybe five minutes before getting out and examining the invasion, before he hesitantly entered his house. A quarter hour later Chuck left and drove his car around the block before returning to the fest, and was pleased to be told that Professor Beck as soon as Chuck had moved, hurried out of his house and moved his car forward a couple of feet and walked happily back into his house. Chuck said to me “He does it every time.” Beck, by the way, was a distinguished scholar. Chuck was a pleasure to know, a habitual stutterer whose locution was faultless when he was seized by an idea. Irrelevant: I envied his habitual suit a couple of sizes too large, a herringbone tweed he bought second hand somewhere in his native Maryland. Chuck’s motivation was obvious, although some might find it mildly sadistic. Professor Beck’s motivation was a kind of obsessive craziness I don’t know the name of.

But the comedy of habit aside, what would we do without it? I must admit there are some habits we’re better without: certain negative prejudices. Later maybe. But now, prejudice now has a bad press, because most associate it with dislike of a racial or ethnic group, as if one has prejudged the group. And yes, prejudice is indeed a prejudgment, but not necessarily unfair and insulting. If I say, “I’m prejudiced against loudmouths,” it is the loudmouth himself (OK—or herself) whose bad manners are unfair and insulting to others; and if I prejudge the loudmouth it’s because previous experience has led me to find him universally offensive, so I will habitually get the hell out of hearing distance. Prejudice is a favorite word of Edmund Burke throughout his Revolution in France. It refers to knowledge which is trustworthy, having passed the test of time so that one does not have to start always at zero.

And yes, therefore, prejudices are habits. And useful. Life is complicated—and short enough—that in every experience we do not have to act as if without previous experience, do not have to weigh every conceivable possibility of possible consequences, can rely on the probability that the regnant experience is comparable to that which seems similar—and thereby avoid going mad and exhausted. I do not have to think to myself, “Maybe this loudmouth is going to surprise me, as possibly when he gets close to his conclusions, his voice will soften to the mellifluous, pleasant, and instructive,” and probably waste a lot of time. No, I’m going to follow my habitual reaction and get out of his way. Perhaps the loudmouth experience will occasionally be the exception, but that will be so rare it will not be worth the hours or months experimenting. Habit is such a valuable commodity no one should habitually dismiss it as “merely habitual.”

The last couple of paragraphs, although the examples are mine, are not in content original. This is essentially William James in a lovely chapter in Psychology (Briefer Course), but my copy was water-soaked in the same flood. I don’t know if James read William Hazlitt (he wouldn’t have had to), but Hazlitt said, “Without the aid of prejudice and custom, I should not be able to find my way across the room.”

***

Racial-ethnic prejudice a habit? Yes, but in a kind of perverse parody of the good and useful and time-saving habits Burke and James and all wise persons endorse.

I have argued at length elsewhere that racial prejudice as we generally characterize it—anti-the other—is a choice, not a psychological inevitability. If you can call a racist judgment an idea—and why not?—John Lukacs was right that “We do not have ideas; we choose them.” Often the choice is a parody of my imaginary loudmouth experience, in which I judge all loudmouths as more or less the same and save a lot of time. I suppose I could be characterized as “anti-loudmouthic.” Maybe someone has an unfortunate experience or two with Latvians and decides that all Letts are the same. Or you know where I’m going: with Blacks, with Jews, etc. Or, oh, how easy it is to avoid mentioning that other prejudice, when Blacks say “Whites—well, they’re all the same.”

Or it is probably more often the case that one grows up in an environment—familial or larger—where he or she simply absorbs a racial or ethnic prejudice not related in any way to his or her personal experience. If one retains that prejudice, for which there is no rational excuse, this is a thoughtless choice become a habit of the mindset. And yes a choice can be thoughtless: I do not have to and often do not choose to shave every morning without thinking about it at all. Let me pretend for a moment. Here’s the pretense: I grew up in a house which had no books. In school I learned that there were books which were not mere textbooks, were instead poems and stories and such, which opened a world which was foreign to my mom and dad. But not wishing to desert my parents and reject their world, although I now know its limitations, I do not become “bookish,” but rather read what is necessary at school only, and do not desert my familial habits. I have made a choice as stupid as that of the offspring who does not depart the distaste for Blacks or the anti-Semitism of his familiar environment. (I reiterate, this “personal” example is a fiction.)

***

Whether one wants to call racial-ethnic prejudice a choice or not, and whether one is comfortable calling them habits or not, they are a blight on the human race. But not all blights are equal. So I warn the reader that I will eventually in this digression say something most will probably find offensive to proper sensitivities.

I grew up in North Carolina, where my first non-familial love was a black kid my elder by four of five years whom I adored, yet nonetheless by the age of ten or so I was slapped out of my chair by my father for calling my mother’s helper a “Nigger.” “Don’t talk like white trash,” he said. I never did again. And I didn’t really feel like that then. And I taught for more than 40 years at a college where the majority of students were of color.

It has been my experience that Blacks are very competitive with Jews as to which have suffered discrimination the most, discrimination obviously allowing a wide interpretation, some people thinking segregation worse than murder. Not even slavery is worse than murder, since a dead slave is useless.

There is nothing positive to be said about chattel slavery, although pre-Civil War Southern “sociology” found much to justify it. But that is a dead issue. Nor is there anything to justify the racial segregation that followed manumission. Although it is possible to understand it. I hasten to add that to understand is not to forgive: it may indeed lead to sharper condemnation. Madame de Staël was wrong that excessive understanding leads to indulgence, although some people may indeed say “I understand” when they mean they forgive: sloppy thinking and sloppy speech can go together.

So, I can understand how anti-Black bias comes about: must I continue to say what that does not mean? Most basic: in a society which is predominately Caucasian anyone who does not look Caucasian is going to look radically different, and although different is what makes the world go ‘round not everyone likes how the world goes. So black is not judged to be beautiful since more-or-most people define themselves as the acceptable standard. Look at me, you others, and despair. If there were a society of predominately very tall people, no matter their color, and a minority of very short people, no matter their color, the tall would “look down upon” the short, both physically and figuratively. Add to these observations the fact that a larger percentage of people than we like to admit have the intelligence of a box of hair.

The possibility and probability of anti-Black bias, for the longer time in American history until well into the 20th century, depended not only upon difference of pigmentation, but radically upon “condition of servitude.” That is, slaves were slaves because they were slaves. Which is not so repetitively ridiculous as it looks. Africans were thought inferior when brought over to America, and would not have been brought over otherwise. Then the assumption of their inferiority continued because it seemed to justify their chattel servitude; then the assumption remained because the assumption had long remained. By which time a Black was a Black not because black (or brown) but because of lineage: some Blacks as “white” (actually a sort of beige) as I am, which has long been the case, long before there was a vice-president named Kamala Harris. The prevalence of this form of racism lasted until it wore itself out, exhausted by evidence otherwise. . . except in the cases of those the mental and moral equivalents of boxes of hair.

All this is understandable, as I say. But not forgivable.

Nor is anti-Semitism forgivable. Nor is it understandable in the same way or to the same degree. But I’m not ready for that quite yet.

There is no one now worth talking with or to who believes in Black inferiority. But being inferior is not the only way to be different. Special athletic superiority is one apparent or possible way, although I doubt it can be explained genetically. I am thoroughly convinced and have argued so elsewhere that “systemic racism” is a fiction. But the conviction that it’s a reality is one way Blacks, or Black spokes-persons at least, seem different (‘though vaguely similar to the more thoughtless white liberals).

There seems so little appreciation for the radical turn-about in the last 50 years in the U.S.—not only the civil rights revolution, which was not exclusively a Black effort by any means. There is the fact of Affirmative Action, which Blacks both insist upon and resent: the resentfulness lying in the fear that one’s advance will be thought a dole-ish gift rather than something earned. And then, or rather now, there’s the demand for a kind of cultural “affirmative action” to which right-thinking people in the majority (by which I mean wrong-thinking) seem willing and eager to yield. You have to be pretty unobservant not to know that now the luckiest artist alive in the States is the Black artist.

As they say on PBS, “all things considered,” American Blacks have not so much to complain about, culturally speaking. Which is not to say there are not heart-breaking moments like the George Floyd Event—which broke non-Black hearts as well. Nor is it to deny the legitimacy of complaints about states trying to make voting more difficult—which I-Me-Myself complain about as well.

***

Nor have Jews much to complain about, politically and culturally, at least not in civilization, by which I mean an expansive “The West,” which includes large land masses in the Pacific where English is spoken. Now. But not always. Anti-Semitism is the oldest anti-Ism in the West, and the longest lasting, and the deadliest. The Holocaust was the worst but not the first mass murder of Jews. Mass murder of Blacks has been relatively rare, certainly not characteristic of chattel slavery: you don’t want to destroy your property. Ironically, slavery thereby “protected” Blacks from murder in the West. Mass murder’s been an intramural game in Africa, although most recently there was the extramural murder of Blacks by Sudanese Muslims, adherents of the so-called religion of peace.

Perhaps the oddest thing about the oldest “racial” prejudice is that it is the least “understandable,” while so many think they grasp it perfectly well. Unlike anti-Black bias, anti-Semitism is not really a racial matter, a Jew is as Caucasian as an Anglo. Nor is it necessarily a matter of religion. One can object to Judaism without hating individual Jews, while, alternate handed, I for instance have no ill will towards individual Muslims but am decidedly anti-Islam, since far from it being the religion of peace I judge it to be the clearly major source of terrorism. No conceivable objection to Judaism as a danger to civilization can be made, even if such a hair-brained objection was made in medieval times. Yes, Jews in the past were called “Christ Killers,” whether that was a belief or an insult thought to be effective, but damned if I can convince myself to believe that anyone can believe it now or even the insult effective—which may be one reason I have not heard the phrase since god-knows-when.

Jews not being of another race, a Jew is not identifiable as different unless he (seldom she) conforms to ancient and Nazi stereotypes. Islam excepted, organized religion, which means in the West Christianity, has effectively disowned anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism, especially Roman Catholicism in doctrine. So how is one to “understand” the persistence of the bias? I see but two ways, neither of which I claim to have discovered all by myself.

First, Western enemies or harsh critics of Israel embrace an anti-Israel point of view, ostensibly opposing Israeli policy, which in many cases translates into anti-Israelis (plural noun) which is hard to distinguish, and perhaps should not be distinguished, from anti-Semitism. For some of the enemies of Israel may be “anti-Israel” simply because they are already anti-Semites.

Second, people do not have to be obvious scum like the mob in Charlottesville, Virginia, shouting “Jews will not replace us,” to be jealous of Jews. Jealous? Why?

The old trope that Jews are good with money and are disproportionately wealthy; the cliché that Jews may vote like Puerto Ricans but earn like Episcopalians. The observable fact that Jews, in numbers out of proportion to their percentage of the population, hold (have achieved) positions of influence in public and cultural life. Instead of “Congratulations!” the jealous grudgingly rasp “Why you?”

And will not countenance the obvious answer: intelligence! IQ statistics suggest that Jews must be, collectively speaking, the most intelligent people in the world, the smartest Caucasians at the very least. Another “why”? I have no firm grasp of genetics; have never known how or if culture can effect mental inheritance. I mean: is acquired learning passed on genetically, not just casually? And of course, Jews are famously “the people of the book.” I am no dummy, was a habitual A student. But I stand amazed how sharper my Jewish spouse is. I suppose she “got it” from her parents, especially her Ukrainian-born father, formally learned in Hebrew but otherwise mostly self-educated, who loved—aside from the major Yiddish writers—Cervantes, Milton, Gibbon, Macaulay, Tennyson, Churchill’s histories, Shakespeare especially, and god knows how many others.

In any case, while Judenhetze, Jewish persecution, no longer exists in the West, anti-Semitism still exists. And it is a response not to anything “negative” (as white bigots think black skin a negative). It is a response to positive virtues. How disgraceful.

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others. His new book is Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Kenneth Francis)

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

4 Responses

Spot on, Sam. I have always thought that the roots of anti-Semitism were envy, a kind of achievement or accomplishment jealousy. Asians are experiencing a similar phenomenon today when you look at quotas and “affirmative” action admissions. When we confuse our social wants with our cultural or national needs, we are well down the slippery slope.

Hi Murph. Jews and Asians have the reputation of high intelligence. Better to be retarded.

Great philosophical start on existentialism and related topics to segway into prejudice and anti-Semitism. Gained a lot. Thanks

Thank you Mr. Henry. I try to construct an essay as well as you do a building.