By Henry Chappell (December 2017)

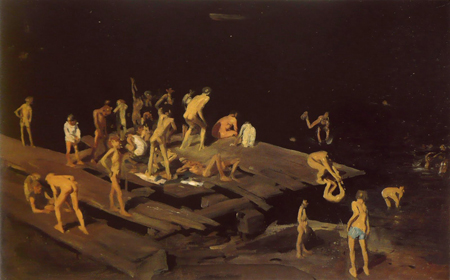

Forty-two Kids, George Bellows, 1902

My mother told me that good boys don’t fight. I can’t say she taught me, for I never saw Mom, a depression-era child of illiterate Kentucky farmers, turn the other cheek.

My father, a son of Harlan, Kentucky, told me, “Don’t start nothing, but if it comes down to it, addle him with the first lick and keep at it until he’s down a spell.”

I sometimes regret that I can’t claim a hardscrabble childhood of mining camp brawls or of being a sensitive outsider suffering among Babbits-to-be. I confess to a comfortable upbringing in an orderly little central Kentucky town. In high school, a modest talent for football compensated for social awkwardness. I dated cheerleaders, majorettes, and other popular girls. I’ve been married to the drum majorette for the past 39 years. Teachers cut me all kinds of slack. Per the script, my buddies and I swaggered about in letterman’s jackets. We never lost girlfriends to rebels, misfits, or artists.

So there: An embarrassment of good fortune and happiness of the most contemptable kind. I can’t blame anybody for anything.

Nevertheless, I offer thoughts on bullying from a sufferer’s perspective.

In my hometown in the 1960s and 70s, parents, lawyers, and the police, took little interest in kids’ bloody noses and cut lips. Teachers broke up fights and sent brawlers to detention or to the principal’s office. Nobody got suspended. Adults assumed kids would fight. We met all expectations.

(I was in third grade during the 1968 presidential election. At recess, we boys held tag-team wrestling matches between Wallace and Nixon supporters. The Humphreys couldn’t field a team. No punching allowed until somebody threw one.)

Early on, I learned to avoid certain older boys, especially when they had an audience. A solitary kid with whom you might pitch baseball would, a few days later in the company of friends, turn into a sneering menace. “You gettin’ smart? I’ll bust your goddamn nose.” Yet there was little danger of actual violence. Intimidation was the point. One adjusted bicycle routes to avoid these terrors.

The more assertive poor white kids formed a class called “hoods.” The boys were athletic and played baseball and football until they got into trouble for smoking or insolence. Hood girls seemed clannish, irascible, defiant, and uninterested in the social concerns of middle class kids. By high school, many already struggled with adult burdens, openly indulged adult vices, and tried to keep older boyfriends out of jail and on the job. We jocks admired some of them from a distance.

I got along with hoods my age. I found the boys friendly, rowdy, inclined to make fun of themselves. You’d see them straddling rusty bikes at middle school football games and, a few years later, in rumbling heaps in the parking lot. At basketball games they hung around the gym entrance, a terror for every timid kid who walked up the front steps.

In elementary school, you lived in fear of an older hood announcing that he was “after you.” A hood classmate would give you the bad news, solemnly, as if warning you for your own good. “Man, I don’t know what you done, but T____ aims to whup your ass. I just thought I’d better tell you.”

In nearly every case, the reason was some variation of “He thinks he’s hot shit.” Or maybe you got smart with somebody’s little brother.

The hoods, including the one who was after you, never missed a Friday night football game. If you didn’t go, word would go around that you were chickenshit. Monday morning, your buddy, who’d been waiting all weekend to deliver the news, would say something like “Oh man, T___ was looking for you the other night.” (Damn, I’d hate to be you.)

So, you’d go to the game. T___ would be patrolling with his hoodish claque. The instant you sat down in the bleachers, you began to dread the unavoidable fourth quarter trip to the restroom. Forget the concession stand. Your buddies wouldn’t fetch popcorn for you. “Hell no, I ain’t gettin’ my ass beat.”

The summer after sixth grade, a friend and I, after finishing our Little League game, stood behind the backstop, watching another friend play. A kid named B___, two years older than us, but barely taller, sidled up and said, “What’s this you two been saying about [his girlfriend] J___?” We had no idea what he was talking about.

B___ had recently moved in from out of state where, according to rumor, he and his brother had gotten into some “real shit.” For most of the year, B___ was an exotic alpha-hood before his contemporaries realized he was just a scrawny creep entirely lacking in hoodish virtue.

But that afternoon at the backstop, B___ was still in his glory. After nodding to our disavowals, he asked if our parents were in the stands.

They were.

He said, “One of these days I’m gonna catch you two alone and I’m gonna beat the hell out of the both of you.”

We looked straight ahead, tying not to soil our pants. For the rest of the summer, I dreaded trips to the ballpark.

I avoided B___ until the fall, when, at a high school football game one of his groupies found me on a foolhardy trip for a hotdog.

“B___ wants to talk to you.” I forgot about hotdogs and followed him to an upper corner of the stands, well away from adults, where B___ straddled a bleacher. He seemed to be studying an open matchbox, as if deciding exactly which match would best light the cigarette that lay there between his legs. I judged he’d grown since mid-summer. His familiar acolytes surrounded him at a respectful distance, watching to see what amazing thing he would do next.

My guide said, “Here he is B___.”

B___ nodded thoughtfully, like he’d done that day at the backstop. “So, uh, Chappell, what’s this you’ve been saying about me?” He never looked up.

I don’t recall my answer, probably, “I didn’t say nothing.”

B___ kept nodding.

Finally, a big, affable, ginger hood said, “Aw hell, B___, he’s done everything you told him to do. Let’s leave him alone.”

The statement made no sense, but I was all for being left alone.

B___, still studying his matchbox, said, “Okay.”

My guide said, “You’d better get out of here.”

I dashed back to the concession stand.

A couple weeks into seventh grade, I learned that the entire eighth grade football team was after me. The news dampened what had been shaping up to be a capital school year. Having turned twelve the previous summer, I took a sudden and keen interest in girls. To my delight and amazement, there had been reciprocation. But, football tryouts went a little too well.

“The guy completes a few passes and starts ordering people around,” was the official complaint. I’d barely spoken, let alone ordered anyone around. Maybe I unwittingly showed insufficient deference. In any case, I had to be taken down a peg.

Social science and pop psychology have long told us that most bullies have been bullied; they can be victims as surely as those they victimize. Responsible adults no longer look at a kid and say, “He’s just a mean little bastard.”

I suspect bullies often grow up and beget bullies. I’m unqualified to suggest nature versus nurture percentages. Decent parents can find themselves stuck with a little psychopath. Cruel parents might raise an altruist.

Bullies know what they’re doing. Given this rationality, it seems reasonable that society can crack down on bullying, marginalize the behavior much as we’ve done with the more open and egregious forms of racism. If you cannot lead with a carrot dangled from the stick, then forget the carrot and drive with the stick. Yet I have little confidence in the zero tolerance policies currently in vogue—automatic suspension for fighting, even in self-defense, for example—for they reduce the victim’s options to endurance or appeal to authority. Then again, I’ve never been charged with student safety, and have no alternative policy beyond “flexibility,” which may be impractical. Certainly, adults should stop bullying whenever they can and watch for subtler cruelty that sometimes follows intervention. Some children, like my younger self, find quiet but obvious contempt worse than active bedevilment.

Perhaps my experience with common bullying will be useful to sufferers of certain temperaments, abilities, and situations. It will be of no use to the most vulnerable among us or those dealing with criminal violence.

Sadism will always be with us. It moves and changes form with shifts in power. No substantial population, regardless of culture and politics, is immune. More troubling, I cannot shake the suspicion that, within limits, bullies have their place—and may even be indispensable.

__________________

So, it began. I’d catch the school bus at 6:30 a.m. Being one of the first on, I usually took the second or third seat. Before I ran afoul of my older teammates, I always hoped the seat immediately in front of me would remain empty until a certain girl got on a quarter way through the route. No longer. The thing I dreaded more than the taunts and the paper wads, spit balls, lemon drops, and M&Ms hitting me in the back of the head was having a pretty girl there to witness my humiliation.

But I was safe for the first quarter hour, even though one of my less enthusiastic tormentors got on right after me. He needed peer pressure. I feel a bit perfidious mentioning him because we became friends a few years later, and he apologized, in his way. Such is the insidiousness and appeal of cruelty, even among decent people.

Worse yet, there were always one or two older delinquents on the route. Mean, stupid, with chin stubble and pack-a-day habits, a few weeks shy of sixteen, their chief joy seemed to be ogling twelve-year-old girls and terrorizing boys the same age. Most came and went until they disappeared for good.

Much to my discomfort, one of these older degenerates maintained perfect attendance. He got on the bus every morning, made his way past me and the suddenly obsequious eighth grade boys behind me, to the rear seat he’d claimed for himself. Before long, the smell of cigarette smoke would waft to the front of the bus. Directly, the backseat despot would take an interest in the fun going on several rows up. An eraser or paper wad would fly past my head. If I turned and glared, a half-dozen boys would claim responsibility.

From the very back of the bus: “Hey Chappell. Come back here. I wanna talk to you.”

No way I’d look back.

Now one of the eighth graders: “Hey Chappell. D___ wants to talk to you. You’d better get your ass back here.”

The bus driver: “Keep your seat.”

D___: “Boy, you hear what the fuck I said?”

Once at school, I’d hurry off the bus and into the gym to gather in the bleachers with my friends and wait for the morning bell. Across the gym, in the eighth-grade section, a few enthusiasts would look my way and grin and joke with each other. “We see your ass over there. Your time is coming, motherfucker.”

Some variation of this happened every morning for the first couple months of the school year. To their credit, my friends stuck with me, but were too intimidated to stick up for me. I would have done no better.

At my middle-school there was a long tradition in which seventh grade athletes were expected to carry the books or equipment of dominant eighth grade boys. An older boy, having endured the same treatment a year prior, would select a younger one to serve as his “pig.” Likely, he’d spent the summer looking forward to bossing around his own porcine servant.

In principle, I don’t object to mild hazing. Carried out within the bounds of tradition, overseen by responsible coaches, a bit of cow-towing to older teammates can build a sense of belonging and paid dues. Humiliation is checked by the knowledge that you and your classmates are enduring what your hassler endured the year before.

The problem, beyond the degrading name, was the informality of the tradition. There were no rules and therefore no limits. Coaches couldn’t be omnipresent. Every group of fifty or so kids contains at least one sociopath eager to lead a game of one-upmanship. What starts as equipment carrying soon leads to some timid kid bobbing for onions in a toilet.

The eighth-grade quarterback was a handsome kid, the most popular boy at the school. Though I was a couple inches taller, I posed no threat. He was an excellent athlete, the coaches’ favorite. Call him C___. Given his stature, he would have his own pig. My tormentors picked me and convinced C___ that I fit the role perfectly.

One morning before school, as I walked into the gym to join my friends in the bleachers, a few of the usual suspects blocked my way. I turned around. There stood C___, smiling, not unkindly.

“You gonna be my pig?’

I said “no,” much to my astonishment.

“Yes, you are.”

I refused again.

Two boys grabbed my arms. The one on my left held loosely. Only a few weeks before, he and I and another boy spent an afternoon diving off cliffs into Green River Reservoir. I had thought he was a friend. The other kid held tight.

Someone said, “Hit him, C___.”

We regarded each other. Still smiling, without a hint of malice, he shook his head and said, “Nah.” I broke free and joined my friends.

Perhaps C___ wondered if I might have a long memory and penchant for grudges, but I think I saw in his eyes and smile a statement: “I don’t do this sort of thing.” A few years later, when I thought about settling scores, I counted C___’s refusal in his favor.

Over the next few weeks the ordeal burned out. By Halloween, I sat wherever I pleased on bus rides. By the start of basketball season, my former tormentors ignored me. That spring and summer I played Babe Ruth League baseball with and against several of them. C___ struck me out nearly every time I faced him.

Next school year, there were wins and awards, girlfriends, sneak outs, campouts, Seven Minutes in Heaven, and boundaries tested. But no pigs. An older hood, nicknamed Runt, found me intolerable and announced that he was after me. Like most others of his tribe, he was plenty tough but not mean, so nothing came of it.

Late summer before my freshman year, much to my horror, the coaches invited me to report to practice with the varsity players. Even more terrifying, I was assigned a locker in the varsity locker room. To the few upper classmen concerned about such things, the early invitation and the locker meant that I thought myself hot shit, no matter my attempts at invisibility.

“Chappell, come here. W___ wants to talk to you.”

I’ve already stripped down to shorts. They’re still in pads.

W___ was an undersized senior who’d barely get on the field during games. “You think you can whip my ass?”

Truthfully, yes, but W___ had an older brother who wasn’t undersized and might have wanted to avenge his little brother’s ass-whipping.

“I never said that.”

“But you think you can.”

“No.”

“You get your ass to the other side of this locker room.”

On the practice field: “Wait ‘til I get set, you stupid bastard. Fucking freshman.” And so on. Accidently touch the wrong guy in the water line and catch an elbow.

Later on, at basketball games, a few friends and I tried to avoid the attention of beered-up juniors and seniors. You’d walk by a little group in the concession area, avoiding eye contact. Still . . . “Chappell ain’t shit.”

Smile. Pretend it’s a joke.

“What the fuck you laughing at?”

Act like you didn’t hear the question. Head back to the bleachers without a soft drink. Well, Jesus Christ, here they come.

“What the hell you mean walking off when I’m talking to you?”

Your buddies don’t say a word. People are watching. Ten or fifteen minutes on, satisfied that enough people have seen your misery, they’ll move on.

I had a girlfriend. We had some history and got on well. Older boys noticed her. To sit with her at a game or to visit her at her locker, to walk down a certain hallway with her was to invite torment. It’s one thing to endure locker room abuse, quite another to subject your girlfriend to it, or to endure it in her presence. I never talked to her about it. I picked my times. I suspect she found my intermittent attention odd. She was patient, but had her limits.

On a Saturday night in January at a basketball game at a cross-town school, I met an older friend and two of his buddies as I left the restroom. At least I thought of him as a friend. I had played pickup football and baseball with him since elementary school. As we passed each other, he gave me what seemed like a playful shove. I responded with friendly vulgarity.

He didn’t take it that way. Full of beer and bluster, in the presence of his friends, he shoved me against the wall and told me what he’d do to a smartass freshman. As I tried to explain that I’d just been messing with him, a security guard separated us and threatened to kick us out. My erstwhile friend went into the men’s room. I hurried back to the stands, shaken, waiting for the inevitable.

The kid, M___, was quick and strong; he’d bloodied up a couple guys his age. Word was, they’d provoked him. Now buzzing, but nowhere near shit-faced, he thought I had provoked him.

I warned my friends. Sure enough, along came M___, his buddies laughing behind him, a big time shaping up. He pointed to the far exit. “If you want a piece of me, step through those doors.”

I can’t be sure now, but I suspect I had made up my mind before M___ and the boys found me. I don’t recall whether I weighed the physical pain and embarrassment of an ass-kicking against the humiliation and self-loathing I’d feel if I backed down. All I know for sure is that I said “Okay,” stood up on legs that felt loose and light and started for the door. M___’s friends hooted in surprise and delight.

I walked down the bleacher steps, amazed, thinking, “In less than five minutes my nose will be broken or my front teeth will be knocked out. I led the way, past the Taylor County bench, where coach Fred Waddle stepped onto the court to shout instructions to his team at the other end of the court. I pushed the bar and opened one of the double doors.

M___ strode past me, off the walkway, into the grass, and over a muddy spot. He raised his fists over his head as if stretching, then lowered them into fighting position. He wore a white turtleneck and white Chuck Taylors; odd thing, memory. We were well away from the lighted entrance but might as well have been standing in broad daylight.

The two friends cackled. Some kind of shit was fixing to happen. I met M___ out in the dark, beyond the mud hole. He threw a hook. I punched him in the face, and remembered little else, even immediately afterward. I just boxed as my father had taught me. Later, my friends said they could hear blows landing. I do remember one of his wild swings; his hand was open, and I knew I’d hurt him. And there were his unprotected ribs. That’s the blow I most remember. The thump. More punches. He landed on his butt and lay back. “I’ve got to puke,” he said.

Unbeknownst to me, my friends had followed us outside after a quick conference. My closest friend announced that he wouldn’t allow me go out there alone. (Probably to be beaten to death.) The other three screwed up their courage and followed. Now, one of them, seeing my ripped shirt, offered me his jacket.

M___ lay there, still threatening. “Goddamn, you wait ‘til I puke.”

One of his buddies, who later became a college friend of mine, said, “He ain’t doing shit. Y’all get out of here. I’ll get him home.” Now M___ was yelling that he couldn’t see. The buddy said, “Shut up, M___. You’re lucky he don’t come over here and stomp your ass.”

My friends and I walked to a little store and bought junk food. After going over the fight several times, recalling that M___ ended up on his back, temporarily blind and needing to puke, we agreed that it could not be said, come Monday morning, that I hadn’t whupped his ass. After exhilaration and disbelief came regret and anxiety. I had beaten up a kid I liked over a misunderstanding.

Next morning at breakfast, I told Dad I had been in a fight.

“What over?”

I explained as best I could.

“You whip him?”

“I reckon.”

“Well.”

Monday morning, I walked down the first floor hall of lockers. Word had gotten out. M__’s locker was near the end of the hall, on the left. He stood there with a few friends, waiting.

“There’s my man,” he said. “We ain’t through.”

But we were. After a few weeks of threats, he dropped it. I worried that if we fought again he wouldn’t be surprised by an adrenaline-crazed freshman. He probably worried that I’d whup his ass again. We played together on the basketball team the following year and got along fine.

The bullying stopped. I sat through ballgames in peace, courted girls. I won’t claim to have earned respect or fear. Any one of several upper classmen could’ve stomped me into a smudge. Rather, the possibility that depredation might come at a price sent my worst tormentors looking for more submissive prey.

Some of my classmates suffered worse bullying with fewer options. Thinking of what truly disadvantaged kids overcome, I reread my own account with embarrassment. Yet kids are driven to misery, lasting trauma, and suicide over less. If I profited from those experiences, I endured them from a well-fortified position. Loving parents had instilled a sense of self-worth. Even during the worst of it, I could look at myself and my bullies and see that it couldn’t last, that in a couple years these assholes might regret their meanness. Not the least was resiliency from a short attention span: “I can’t bear this another day . . . Hey, a girl!”

I plead guilty to numerous acts of high school assholery, but I don’t remember ever intentionally intimidating or humiliating a schoolmate. Or so I tell myself.

During my short, unremarkable collegiate football career, I saw little bullying. Among young men accustomed to high status back in their various burgs, attempts at domination usually turn violent. From the all-American defensive end down to red-shirted freshmen, we understood that anything started would have to be finished, and that in the chaos and confines of a locker room fight, that crazy son-of-bitch from Slaughters or Pikeville or Hyden might end your career and lower your IQ with a roundhouse right. The team was an even mix of black and white. Most of the black kids came from cities. Many of the white kids came from the hollows and small towns. The team weight room was a place of music, laughter, and raillery where freshmen, upper classmen, trainers, and coaches mixed easily.

About halfway through my freshman season, a cocky, older defensive back known for going about campus shirtless, in a short leather vest, got crosswise with a freshman linebacker who was barely hanging on. A working-class kid from Louisville, he’d been a monster in high school, but at the collegiate level he lacked half a step.

One drizzly afternoon as we walked down the hill toward the practice field I heard shouts and the clack of shoulder pads behind me. Coaches rushed in. The older kid got up staggering, his helmet knocked off. Blood poured from his mouth. His upper front teeth were broken off at the gum. An assistant coach dismissed both players on the spot. Practice went on, a little more polite and subdued than usual.

I assumed I would graduate college and enter a professional world inhabited by honest, reasonable people who treated each other with courtesy.

The illusion lasted about a week into my engineering career, when I went to work as an associate for a senior engineer who seemed well along the autism spectrum. Certainly, he was honest and competent. Courteous he was not. That he was consistent, fair, and occasionally generous, kept things tolerable and often satisfying. At one time or another he threatened to fire every member of his staff, usually in front of colleagues, usually over some trifling incident, yet I can’t call him a bully, for when one of us really ran off into the ditch he tended toward gentle helpfulness.

I’ll pause here to dispel the stereotype of engineers as quiet geeks. I worked for a large defense contractor. Many of our senior people came out of the military. Think brogrammers after a few drinks. Yelling, swearing, and high-volume laughter were rife, all the more so in the vault-like classified area where I spent much of my career. Ass chewing, threats, and occasional thrown tools, usually due more to sleep deficit and stress than from mishaps or affronts, neither required or received the attention of the Human Resources department. Thus, a typical description of a productive trip to some distant lab or laser range: “I got fired three times and quit twice.” Those were good years with good people.

Yet, amid the agreeable mix of competitiveness and teamwork, sadists found victims. The first instance I noticed involved two technicians: the bully, a young, bright little stoat who attacked the most mundane tasks with unnerving ferocity, and the victim, a middle-aged man, noticeably slow, but conscientious and adequately skilled. The younger technician and I were in our late twenties at the time. I had never imagined a kid would treat an elder with such viciousness—sneering, berating, keeping up such a steady stream of harassment that the older man could scarcely think. Since neither man worked for me, I reported the abuse to their boss, a fellow engineer who allowed it to continue until the victim slipped into depression and eventually lost his job. I should’ve done more. Some thirty years on, I can’t shake images of a husband and father near tears, confidence gone, his forehead propped in his trembling hand.

The corporate bullies I knew fit no physical pattern, but all were extroverts, often funny. I sometimes found them hard to dislike, but then they treated me well enough. At a glance, their victims seemed random, but I came to believe that sadists sense the subtlest vulnerability, are aroused by it and drawn to it like rattlesnakes to body heat. I’ve wondered if they’re conscious of their lust beyond the basest level. Perhaps they “believe” they’re responding in frustration instead of calculated savagery, that to respond to a reasonable objection from a distinguished engineer with, “Look, goddamn it, if I hand you a paint brush and tell you to paint the wall, you’re gonna do it” is hard-nosed management; or to openly leer at a staff member’s grown daughter is an alpha prerogative; or, in a room full of people, to yell “Don’t be a fucking idiot” in answer to an innocuous suggestion is somehow indicative of a commanding presence.

I’m disinclined to give them even that much credit. Adult sadists, like their middle school counterparts, know how to get their jollies. From a moral standpoint, whether or not they’ve suffered bullying themselves matters not one whit.

I found corporate victims inscrutable. Usually they enjoyed the respect of peers and functioned at high levels. I saw no vulnerability other than willingness to accept abuse from certain people. Did their bosses have something on them? Were they financially desperate? These weren’t single parents struggling to feed kids and pay rent. Maybe they were terrified of confrontation or change. Did they bear any responsibility for their suffering?

During the worst of my middle school troubles, my father gave me some advice: “Don’t let them see you cry.” I know how those words hit the enlightened ear, but that morning in 1972, Dad’s advice seemed sound and seems so now. Likewise, “Addle him with the first lick and keep at it until he’s down a spell.”

________________________

Henry Chappell has appeared in The American Conservative, Orion, The Land Report, Texas Wildlife, Concho River Review and many other regional and national publications. He has authored six non-fiction books and three novels, including his latest, Silent We Stood (Texas Tech University Press 2013). You can learn more about him www.byhenrychappell.com.

Help support New English Review.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link