By Daniel Mallock (December 2017)

The Moment of Truth I, Paul Gauguin, 1892

In 1974, Hiroo Onoda, a young 2nd Lieutenant and Intelligence officer of the Imperial Japanese Army, walked out of the jungles of the Philippine Island of Lubang and surrendered. Ferdinand Marcos, then President of the Philippines, received Onoda’s sword, then immediately returned it to him and officially forgave all his acts of violence and theft committed during his long war. Refusing to believe that Japan had been defeated and rejecting communications from Japanese government officials and pleas from family members as enemy tricks, Onoda fought on in the jungles of sparsely populated Lubang island for 30 years after the end of World War Two.

In his memoir, No Surrender: My Thirty Years War, Onoda described his deep belief in the propaganda of wartime Japan, his faith in his superior officer’s promise that Japanese forces would come back for him, and his rejection of all those information elements that did not fit with his preconceived ideas about Japan, the war, and his duty. When a young adventurer from Japan, Norio Suzuki, found Onoda, and told him that the war was over, the then 52-year-old soldier replied that he would not surrender or return to Japan without specific orders from his commanding officer.

In the last year of the war, prior to leaving for Lubang, Onoda received this order: “Under no circumstances are you to give up your life voluntarily.” This directive was contrary to the tradition of Japanese forces, who would commit suicide rather than be taken prisoner, which was considered a dishonor. Told to fight on no matter how long it might take, Onoda promised to be faithful to his orders and to his sense of duty.

The news of Onoda from the Philippines electrified Japan. Onoda’s former commander, then in his 80s and working in a bookstore, travelled to Lubang with an official delegation. The former commander read aloud Onoda’s official orders relieving him of duty.

Japanese society greeted Onoda with astonishment and awe and showered him with attention. Stunned by the changes in Japan and the obsession with commerce and the acquisition of wealth that he saw, he moved to Brazil for a time but later returned to Tokyo, where he died in 2014.

Two of his comrades had died over the years in fighting with the locals or the Philippine forces who were looking for them; his last two years were spent alone in the jungle. When the final helicopter lifted off, Onoda saw the island from the air for the first time.

Ten minutes later the helicopter I had boarded rose off Lubang, flailing the grass around it. Through the windproof glass I could see Kozuka’s grave, and gradually the whole island, grow smaller and begin to fade.

For the first time, I was looking down upon my battlefield.

Why had I fought there for thirty years? Who had I been fighting for? What was the cause?

Onoda’s memoir closes with these unanswered questions.

In a news conference, Lieutenant Onoda said: “I was fortunate that I could devote myself to my duty in my young and vigorous years.” Asked what had been on his mind for the last 30 years, he replied: “Nothing but accomplishing my duty.” (NYT, March 13, 1974.)

Duty is a matter of central consideration in all societies; that is, what do we owe to one another and to the society at large? These related questions must follow: What do we owe to our families? What responsibilities do we have to friends and strangers?

Duty is both a personal and a national matter. There are fundamentally understood duties that all who recognize moral and decent behavior understand, several are given here by way of example: The adult child’s duty to elderly parents; Parent’s duty to care for their children; Society’s duty to educate the young, etc. No society can survive when its citizens have no sense of duty to one another and to central societal concepts larger than themselves.

In times of trial, we are encouraged to “do our duty.” This duty is often not delineated as it is understood to be commonly known. Doing our duty is to do what is right, no less, but often more. This is a common concept in American life. We understand what is right from our upbringing, the morality of the wider society in which we live, our religious and ethical training, and from our Constitution and laws. Different cultures have differing concepts of “what is right”—some much less “right” than others.

Doing what is right is the essential duty of everyone in a functional society of decency and justice. In his instructions to a jury in the late 1790s, then Tennessee Supreme Court Judge Andrew Jackson once said, “Do what is right between these parties. That is what the law always means.” Decent people always aspire to do what is right, sometimes unsuccessfully. But, the impetus to “do the right thing” is ever there and stands as a fundamental point of guidance when decisions must be made. Perhaps this, then, must be the answer to Onoda’s unanswered questions as to “why?”

Onoda was a man driven by a sense of duty. On his return to Japan, he was a man as if from another planet—few in the post-war generation could conceive of such sacrifice for, and dedication to, duty. Robert E. Lee, now diminished and widely reviled as little more than a slave holder and defender of the slave system was long revered (until recently) for his sense of duty, and his devotion to his people and country. As with many Americans of his time, he saw his country as “Virginia” and not the United States. This was the foundation of the philosophical and political conflict that began before the Constitutional Convention and that finally engulfed the country in war. White House Chief of Staff General John Kelly noted this in an interview with Laura Ingraham in late October, 2017.

I would tell you that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man. He was a man that gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was always loyalty to state first back in those days. Now it’s different today. But the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War, and men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had them make their stand.

Defending Robert E. Lee and explaining the decisions he made in the historical context of his time is not to be confused as a defense of slavery or of the slave system. All decent and reasonable people condemn the abomination that was the slave system wherever and whenever it might appear.

While it is difficult to deny the idea that slavery was the essential cause of the Civil War, it is also just as true that few Confederate soldiers fought and died to sustain it, or that the preponderance of Federal soldiers fought for emancipation. For most of the soldiers who fought the war, it was about either Union or Disunion (i.e., Confederate independence). Historian James MacPherson makes a very strong case for this interpretation in his excellent book, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War.

This does not mean of course that, in the pursuit of one’s sense of duty, mistakes cannot be made. As is the case with many historical events of great magnitude, the causes of the Civil War are complicated and remain controversial. Simplifying this complex tragedy to only a single issue is historically inaccurate and fuels the fires of contemporary partisanship. Such a simplified approach fills the coffers of those who would once again sunder the great ties that bind us all in our American union and, most importantly, nullifies those painful lessons learned during and after that great struggle. Can there be anything more absurd and destructive as refighting a conflict long-ago resolved?

In closing his first inaugural address, Lincoln made a plea for reconciliation, for union, and for peace. This eloquent plea fell on deaf ears in many states, unfortunately.

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Robert E. Lee, in a pre-war letter to his son G.W. Custis Lee, stated his case for the importance of duty.

In regard to duty, let me, in conclusion of this hasty letter, inform you that nearly a hundred years ago there was a day of remarkable gloom and darkness, still known as ‘the Dark Day’—a day when the light of the sun was slowly extinguished as if by an eclipse. The legislature of Connecticut was in session, and its members saw the unexpected and unaccountable darkness coming on they shared in the general awe and terror. It was supposed by many that the Last Day, the day of judgment, had come. Some one [sic], in the consternation of the hour, moved an adjournment. Then there arose an old Puritan legislator, Davenport of Stamford, and said that if the Last Day had come he desired to be found at his place doing his duty, and therefore moved that candles be brought in, so that the House could proceed with its duty. There was quietness in that man’s mind—the quietness of heavenly wisdom and inflexible willingness to obey present duty. Duty, then, is the sublimest word in our language. Do your duty in all things, like the old Puritan. You cannot do more—you should never wish to do less. Never let me and your mother wear one gray hair for any lack of duty on your part.

When duty is fulfilled for good or ill the result is that people are driven, often to extremes, to do what they believe is right and necessary. Was the Japanese Imperial Army’s mission wrong? Yes. Does this negate 2nd Lieutenant Onoda’s extraordinary personal sacrifice in fulfilling his duty? No. As a product of his time and of his country and a man of exceptional character, Onoda’s 30 years on Lubang Island are sensical and understandable—

even laudable. The same can be said for Robert E. Lee doing his duty to the extraordinary lengths that he did in both the US and CS armies, during the Mexican War, before the Civil War and, to his great credit, after Confederate defeat as well.

Does this then cause a moral/ethical conflict in so far as all those following their sense of duty are somehow excused on account of it, or that following one’s duty is somehow exculpatory for crimes committed while doing so? It does indeed.

If the mission itself is wrong or immoral, can we of the generations that follow look back in admiration at what those men or women who were duty bound did to uphold these wrong missions? Can we separate character from actions or mission to such a degree that some aspect or element of the persons in question can be “rescued” or separated from their association with and support of a national or personal mission that is wrong?

These are fundamental questions of history and historiography, of morality, ethics, and law. How do we—

as students, historians, citizens—

talk about someone who participates in a mission or project that is wrong and they explain their actions thusly: I was doing my duty? The examples of Hitler and Benedict Arnold, for example, are clear as day—Hitler was an evil man; Arnold was a traitor to the American Revolution and the new United States. Our investigations into their character are generally constructed around the question of “why,” i.e., why did they do it? The history of the world is contrary, jarring, and confused. For example, many in France see Napoleon as a heroic figure while most of Europe and the United States view him as a tyrant and conqueror. In Japan, as in Germany, generations who followed WW2 rejected the aims and actions of the previous governments and of their parents and grandparents. With this widespread rejection of their militarist past how then was Onoda greeted with warmth and admiration when he returned to Japan?

How do we unite our rejection of their mission with appreciation of the servant of the nation who strives to uphold the wishes/purposes of his country? One must look to the Nazi problem. Can Nazi soldiers in retrospect be “rescued” from their involvement in upholding the Nazi program and state? Can or should they somehow be “rescued” from their involvement with Nazism? And what if they are draftees, young men or women called by their country to serve and fight? Are they to be blamed in the same way that their leaders are? Does the matter devolve to the simple resolution of a statement such as “they did their duty in a bad cause?” Is that the summation of the problem? No, it cannot be.

How do we contrast German opponents of the Nazi effort with those who supported it? We must hold Sophie Scholl and her friends in the White Rose to a much higher degree of honor than those who supported the Nazi aims. Kurt Gerstein, a participant in the crimes himself, came to see that what he and his country were doing was a great and horrible crime. He took action at significant personal risk to warn the world of what he knew and had seen of the Holocaust. They (and others like them) deserve extraordinary esteem and admiration for their courage in recognizing and acting on the knowledge that the aims of their country were wrong.

There are levels of honor and levels of appreciation and these must be understood and contrasted with the actions of a nation. When a nation state goes to war, the citizens are caught up and made to participate in it. When the cause is bad, the entire nation is held morally accountable to lesser or greater degrees, not only individual leaders. Even when people are involved unwillingly still the error of the enterprise itself is a stain upon every participant’s actions and character. In this way, some elements of a person can be sometimes rescued, depending on the person, his actions, his mission, and perhaps what he did afterwards—if he survived his particular conflagration.

Because humans are contradictory, history is a great contradiction.

Onoda could have said, “I did my duty as I understood it and was ordered to do”; Lee might have said, “I did my duty for my country and my people as I understood them”, Sophie Scholl and her White Rose friends might have said, “I did my duty despite what my country and society told me to do!”

Some crimes committed in the course of doing one’s duty are unforgivable. For example, there can be no forgiveness for Hitler, Goering, Goebbels, Heydrich, and many tens of thousands of others like them. A sense of duty without morality and ethics, or one that is corrupted by immoral or unethical systems is a reason for horror and disapprobation, not appreciation. Such things are the foundations of aggressive war, national evils, and crimes. They represent a great danger and likely will forever.

What is to be done with the vanquished enemy? What is to be done when the war is over and peace returns? How are the defeated to be received? What can be the reaction when someone has taken a destructive and morally questionable course? What is to be done when the one-time enemy is your neighbor? What do citizens of a defeated country say to their returning soldiers? How does peace prevail when the violence is over, and the guns and flags all stacked? In the case of the United States’ Civil War, the answer was to forgive and look to the future.

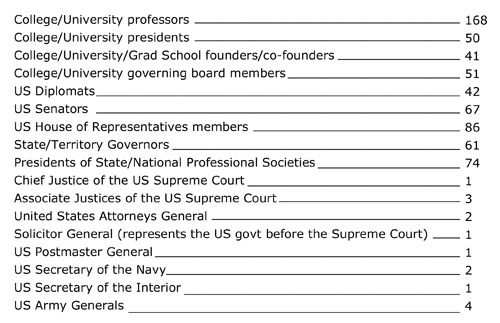

When the American Civil War ended, Confederate soldiers and civilians were reintegrated back into the mainstream fold of the re-United States. Defeated southern states rejoined the Union, a wave of reconstruction, forgiveness, and acceptance characterized the country. The former Confederates were normalized and returned to citizenship, so much so that they participated at every level of civil, business, military, and government affairs in post-war American society. Noted Civil War historian Stephen M. Hood recently compiled a list of former Confederates and their roles after the war. That so many ex-Confederates could hold such important positions of trust and authority in post-war America clearly demonstrates that Americans had forgiven their southern brethren and moved on into a future of unity and cooperation. This is not to say that this process of reconciliation was easy. It wasn’t.

What is it then about so many loud and angry people of the current generation that they feel morally superior to the survivors of the War and the generations that followed them? How is it that these monument destroyers and bitter critics of today—many generations removed from the events of the war—think themselves somehow more outraged and offended than the participants themselves (and their children)? For these modern morally-superior revisionists, the issues resolved on the battlefields of the War and followed up with post-war acceptance and reconstruction are now, in their view, somehow unresolved? This viewpoint of anger and the cancellation of old forgiveness is destructive of the country, of national cohesion, and nullifies the closure achieved by our forebears. It is akin to throwing a worthy gift back in the face of a well-meaning gift-giver. It is a great injustice to the present and the past.

How can this current generation understand themselves to be now so morally outraged at slavery, at secession and other matters of controversy of past generations that the forgiveness, understanding, and resolution of the participants and survivors is now nullified? There is a theme here: nullify the lessons of the past, ignore history, reignite old flames of bitterness and anger long extinguished. It is all anti-historical and self-destructive.

These old wounds long healed were resolved by the generation that fought the War. What gives the present generation the right or a sense of (mistaken) obligation/duty to cancel the forgiveness shown by those participants and survivors of the war? How can the replacement of reconciliation and forgiveness with a new modern moral outrage, anger, rejection, and indignation be justified? There is no duty to rip out old sutures in long healed wounds and shatter the peace so dearly bought by our forebears.

What follows is a partial list of positions held by former Confederate soldiers after the Civil War. If American society had not re-unified and reintegrated, if the fighting generation and their children (and generations that followed, up until now) had not forgiven their former foes and moved forward, if the pain and anger of the war hadn’t been resolved and buried in the graves along with the heroes and victims of that unfortunate war, this list would be empty.

Always watchful for a twisted sense of duty or failure to do one’s duty in a moral and ethical context of decency and justice, we’re obligated as a society to call out (and rebuke) those who fail and to acknowledge with appreciation those who extraordinarily succeed. Doing this reiterates our purposes and causes as a country while reminding us that civil society and national existence is founded upon our duty toward others. It also reiterates our national identity and where all of us fit in relation to it.

Duty is not a concept reserved for those who serve in the military. Doing one’s duty is often a thankless and selfless act. Those who are duty bound are the safe-guarders of our national existence. The duty-bound keep alive the standards and values of freedom and justice—an often thankless task that all Americans who love the Constitution and their country admire and appreciate.

Onoda’s reappearance in Japan after 30 years fighting and hiding in the jungle of Lubang, was a shocking and powerful reminder to his countrymen of the mid-1970s—awash in materialism and rapid economic growth—of an ethos of selflessness and dedication rarely then seen. These are timeless and essential concepts. Perhaps the warm welcome he received was not at all about Onoda’s service to the Empire, now gone and rejected, but rather his strength of character, his self-sacrifice, his love of country, and his dedication to duty.

Quoting the Mainichi Shimbun, the New York Times reported on March 3, 1974, “’Onoda has shown us that there is much more in life than just material affluence and selfish pursuits. There is the spiritual aspect, something we may have forgotten.’ Other newspapers made similar points.”

There are things that we, too, have forgot.

Shocked by an ever-widening scandal of sex crimes, abuse of authority, harassment, hypocrisy, and myriad forms of disgusting unethical behavior including rape among those in the rarified worlds of entertainment, journalism, and government the country awaits its own reminder as to what it is we’re all about; what it is that we stand for, and what lies at the core of our national character. These are not unknowns, just forgotten for the moment.

As the end of the year 2017 approaches, it is difficult to avoid the ongoing scandal. The often-daily denunciation of public figures in entertainment and politics and exposure of hypocrisy and criminality among the powerful and respected has rocked the country to the core. In fact, the previous great stories of the moment—the decades old conflict with North Korea, Islamic terrorism, and political/social conflict between left and right—have all been knocked off the front pages of both legitimate and fraudulent media outlets. The public denunciations, mea culpas, apologies, denials, and investigations all represent a long-overdue sea-change in how we deal with liars, hypocrites, and criminals—most particularly in how such reprobates interact with women, subordinates, and children.

Many have expounded on the widespread nature of the scandal, and the very public and powerful people among the growing ranks of the victims and the denounced. Perhaps more jarring than the suffering of the victims, or the arrogance or regret of the accused is the devastating hypocrisy of those self-proclaimed champions of women and the oppressed who are apparently guilty of the very abuses and crimes they themselves have for so long condemned.

In this extraordinary mea culpa statement, Charlie Rose, the now disgraced former journalist and interviewer, wrote:

“In my 45 years in journalism, I have prided myself on being an advocate for the careers of the women with whom I have worked,” Rose said in a statement.

“Nevertheless, in the past few days, claims have been made about my behavior toward some former female colleagues. It is essential that these women know I hear them and that I deeply apologize for my inappropriate behavior.”

One highly placed male New York Times reporter was recently suspended by that publication pending an investigation into multiple allegations of sexual harassment. Just one month prior to the allegations being made public, the journalist wrote the following in an October social media post:

Young people who come into a newsroom deserve to be taught our trade, given our support and enlisted in our calling—not betrayed by little men who believe they are bigger than the mission.

A young female colleague stated that she did not experience such decent and professional treatment from him. Regarding an incident with the male journalist that she says occurred in June, she wrote that “he kept saying he’s an advocate for women and women journalists . . . That’s how he presented himself to me. He tried to make himself seem like an ally and a mentor . . . Kind of ironic now.”

A spokeswoman for the publication asserted that the allegations, if true, were “. . . not in keeping with the standards and values of The New York Times.”

Standards and values are the fundamental drivers of duty. Duty is the embodiment of those things; failure to uphold standards and values that one says they believe in, and that are generally known to be shared values across the majority of the culture and the wider society (many or most of which are sustained by law) is a failure to do one’s duty.

We are in the jungles of Lubang now, demanding that justice be done and standards and values upheld. Demands for the powerful and those in positions of authority to find the truth, uphold their trust and their oaths, and that people do their duty ring out daily.

It is incontrovertible that we have a mutual duty to one another as Americans, as citizens of an enlightened and free country. All of these questions of morality and ethics and of law and personal responsibility must be asked; only in this way can we learn the painful and challenging human lessons of history and of the present day. It is by asking and answering such questions that the most important lessons of all are learned.

We are in the dark jungles of Lubang. There are no rescue parties coming for us. We must make our way out, and do it together. There is no option. It is our duty.

__________________

Daniel Mallock is a historian of the Founding generation and of the Civil War. He is the author of Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and a World of Revolution.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Daniel Mallock, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting articles, please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link