by Anthony Mazzone (May 2020)

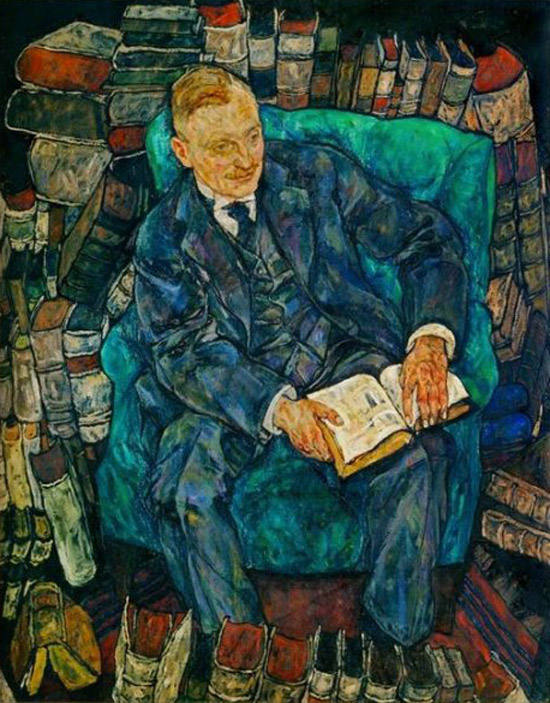

Dr. Hugo Koller, Egon Schiele, 1917

“The whole world groaned and was astonished to find itself Arian,” so wrote St Jerome about 379. I understand that feeling, for something similar has happened to me. After more than threescore years of a life intimately interwoven with acquiring, stacking, arranging, admiring books, I groaned and was amazed to find myself no longer a bibliophile, but a Kindle-ite. Understand: I am not just a catechumen, but have for many years been distinguished by my zeal in rendering full submission of mind and will to the dogmas of Orthodox Bibliophilia. Even as a neophyte my ritual practices were extreme: deliberately planning long layovers in strange cities in order to haunt the used bookstores, plotting to get locked into the university library stacks for a night of study, giving the acquisition of books precedence over the purchase of hard necessities. Books were the lares and penates of my household, icons of a sort made of paper and cardboard. I would baptismally annotate each new book with date acquired, then carefully classify it—by author within subject—before arranging it on my shelves. Indeed I was so scrupulous as to build many of those shelves myself. Sometimes I used the hallowed materials of cinder block and plywood. More often I put together some unpronounceable Ikea contraption. Thereafter each book joined a congregation whose mute companionship embraced me for years: all to the greater glory of the written word, preserved in 20 percent ragweed paper. Oh yes, I ardently carried lists of books about in my wallet. I eagerly scoured my friends’ bookshelves. I was, in short, a fundamentalist bibliotaph.

Now I abjure, disavow, and admonish those doctrines. I’ll take my stand: if I want to read King Lear, and a fine annotated edition is on the desk near me, and the same available on Kindle, I will reach for the Kindle. Every time. Yes, I now prefer my books delivered electronically through the ether I know not how, to appear on a screen with no heft, no pages, no ink or paper, immaterial pixels whose production and delivery is as opaque to me as the nature of gravity.

If this is offensive to your pious ears, please know that I did not apostatize overnight. There was a furtive glance at a Kindle here, an iPad there, a magazine displayed on a monitor in full and customizable color. All resistance was finally overcome when I discovered that the entire Summa Theologica was available to me within minutes for 99 cents. My apostasy is only strengthened because all the volumes of the Rambler and Idler are downloadable for free. FREE!

Grand Inquisitor: You, sir, are depriving posterity of humanity’s intellectual inheritance, failing in your sacred obligation to hand on that which you have received, the best that mankind has thought and said. Even worse, you dare to disavow your own personal library, painstakingly curated throughout your lifetime, and which now stands as a memorial to your entire intellectual existence.

Respondeo: I have a nightmare. After I am gathered to my Father’s, I look down to see my children assembled at the house, facing those Ikea shelves full of my curated books. They execrate my name as trash bag after trash bag is filled and hauled off to the Montgomery County Recycling Center. Having their own interests and passions, they are not likely to perpetuate mine.

Grand Inquisitor: Books, apart from their content, are works of the printer’s art. Think of the fine leather gold-leafed covers, the smooth papers, those fonts crafted for beauty and clarity. Hold that work of art in your hands, take comfort in its solidity, those rounded spines. It is the supreme totem of civilization.

Respondeo: The books in my collection exhibit no such examples of the printer’s art. Most are mass market paperbacks, far from artisanal, with spines glued and not sewn. I just pulled a copy of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot from my shelves. It’s a Signet Classic edition that cost me $1.75 when I bought it in December, 1974. The pages are yellow and brittle. The odor is not that of goatskin or clothette but of dust mites which must be either born of spontaneous generation or some unholy concourse between ink and cheap paper. For forty-five years I absurdly transported those mites from one dwelling to another. The book has served honorably. My notes and underlines show that I was ardent at the time. But I now abjure that book and hurl it into Gehernna! When I re-read The Idiot it will be on my electronic device, dust and odor free, in the best translation. I will adjust print size, contrast, color to my liking. As for holding a fine binding in my hands—were I tempted to such soft pleasures I would cover my device in exquisite Tuscan leather with a distinctive warm, natural fragrance.

Grand Inquisitor: Reading should not be passive. You have to take notes, underline, consult reference materials.

Sed contra: It is quite easy to highlight passages on my Kindle. Taking notes thereon requires no additional notepad or writing instrument, encyclopedias and dictionaries are built right in. Furthermore, my notes and underlines are searchable. I can even make them into flash cards for summary review. Let’s see, what was it that Cicero said about the harvest of old age? I stay in my chair, grab my 7-ounce Kindle, find De Senectute, tap the screen a couple of times and in a few seconds . . . ah! here is the passage I highlighted back in 2014: “The harvest of old age is the recollection and abundance of blessings previously secured.” The tech geniuses have even found a way for me to lend these books to others, and best of all: never have to worry about getting them back. As the loan expires, for all I know in a puff of smoke on my friend’s screen, my pixels are restored to me.

Grand Inquisitor: Technology is impermanent and business is fickle. How can you be sure that these sterile books, stored you now not how, will be available to you fifteen, twenty years from now?

Respondeo: It’s an even bet as to which one of us will be around in fifteen or twenty years. In the meantime I have a personalized library of the world’s great literature in my pocket at all times.

Confiteor. I retain some longing for the fetishes and comforts of my earlier faith: the dusty atmosphere of old libraries, the companionable comfort of a room lined with books. I confess to keeping a few ritual amulets: volumes signed by the author, rare editions, those that evoke pleasant memories. I still wander into libraries and book stores from time to time. Only now it’s as an observer, not a member of the congregation.

Please understand that though I am a bibliophilic heretic, I am without absolutism or missionary zeal. Though I myself need no extra mediator between me and the author, I am happy to leave you to your books if you will leave me to . . . well . . . to my own devices. In fact I have no hesitation in cheering the continued production of physical books, or in affirming that printed pamphlets, newsletters, samizdat are necessary for civilizational survival. I’m very aware that we would not have the Book of Tobias today if it were not physically preserved in the Septuagint, the Codex Sinaiticus, even fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls. I admit that there will be no equivalent of the Dead Sea Scrolls for EPub or Mobi. So you see, I’m not completely excommunicate.

Credo: that literature is the formative influence of a society, that a culture loses its mind when it forgets its belletristic inheritance. I lament the decline of literacy, eschew the predominance of pictures over words. But none of this is vitiated by my new faith. My argument is instrumental, having simply to do with the dissemination of words. I am ecumenical in my support of that dissemination: let a hundred flowers of publication bloom in all formats and by all means. While I can’t help but rejoice at the digital revolution’s overthrow of the gatekeepers of content, I fear that this revolution, as always, will eat its own. So, again ecumenically, I anathematize the priests of high tech who adjust algorithms, manipulate search results, de-platform all but allowable opinion. Écrasez l’infâme

So here I stand, content to dree my weird (I know you will google that, not scurry to your OED). I ask you to look into your soul: do you not adhere to some of the secondary dogmas of my heresy? Do you really long for the scratch of fountain pen against paper, for typing ribbons and white-out? Do you really want to go back to bashing your fingers against the keys of a manual Smith Corona, to enduring the clack of an IBM Selectric? So hurl your anathemas if you must, Torquemada, but confess: Your own magnum opus is being written on a computer. You are using word processing software. Eppure, si muove.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Anthony Mazzone studied Comparative Literature at LaSalle University and the University of Illinois. He sometimes publishes essays in traditional Catholic journals and cultivates eccentric interests such as medieval Italian poetry and stride piano. He is a long-time civilian employee of the Navy and now lives in the small town of Narberth, PA where he watches grandchildren and gets to play with dogs.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link