At a Break in Rehearsal for Merchant of Venice:

A Dramatic Work

by Evelyn Hooven (January 2020)

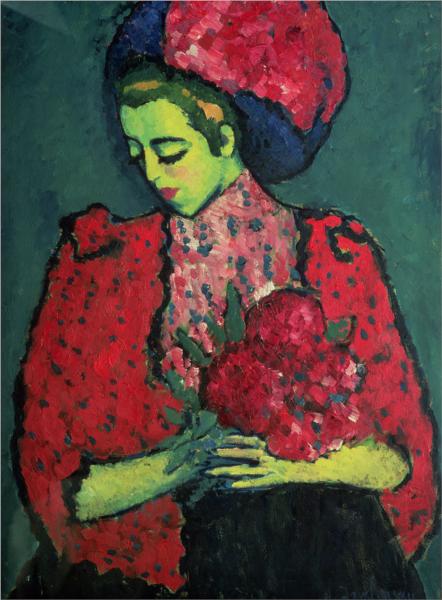

Young Girl With Peonies, Alexej von Jawlensky, 1909

A Note: The actress speaks sometimes through the role in which she has been cast, and at other times as an artist who knows her script and is exploring. Occasionally these factors converge.

Rehearsals will resume tomorrow. This break has not been easy. Seth is such a good director, I’d hate to disappoint him. “We need more life, not, as you know, through tricks or gimmicks. Of the many recent productions, let ours ring the truest.”

He liked my Ophelia and also, when we did The Seagull, my Nina. I remember with Nina feeling a new burst of energy when I rediscovered her: no longer the country girl daydreaming about actors and writers in the great world out there. I could find what she was doing, what she had: no charmed celebrity, something lesser, even shabby, but there’s a force she generates out of nowhere for her actual life—new found daring and competence. There are roles in regional theatres, parallel train schedules for the world she now inhabits. Without the ardor and shine of daydream, she summons daily courage—no self-pity. Now she can claim her life.

Later that season I would rediscover in Ophelia’s activities an energy she gathers through necessity and drastic solitude: she puts together from her pastoral habitat botanical remedies suited to their recipients, extending her version of hospitality as far as the court of Elsinore itself. Here, your majesty, these are for you and, here, along with these, is advice for their use.

For Ophelia and Nina both, there was life newly perceived, not yet lived through, that strangeness, freshness.

Next to them Jessica feels—as of now—almost dimensionless. As Jessica I’m confined to nearly a prisoner in my sombre father’s ghetto. I want out. I want to be a contemporary young lady, somewhat well turned out, if possible. I’ve fallen in love with a young gentleman who loves me. We’ll elope. My father’s absence for even a few hours, with keys he leaves with me, will provide the means. That’s most of what I know. I’m aware there are dimensions I don’t yet see.

Seth did suggest for each of us some improvisation as a focus. For me—the bond and deed of gift. It’s not like Seth to be deliberately enigmatic, so I was puzzled. The bond? I’m not even in the courtroom when Shylock makes his case. Seth’s reply was “Are you sure?” As for the deed of gift announced a few lines before the end, though I’m on stage with the others, I have, through that last scene, no lines. “Lines are not the only way towards your performance. Try a kind of actor’s journal, your own version of a postscript.”

I’m trying not to get lost . . .

When Lorenzo and I elope, I am disguised in male attire as his torchbearer. We journey by gondola amid music and other varied masquerades this festival night.

When I finally have a chance to empty my pockets of their hasty treasures, I recognize among ducats and jewels my dead mother’s ring—her gift, I recall, to my father when they were young.

Was Shylock ever young? He was. And someone loved him, gave him her special token.

Though I’m startled to see my father’s turquoise, best keepsake, I trade it for a monkey. I’m running away from home. Let the older generation take care of itself, without asking what if it can’t.

In a personal ceremony, swift and thoughtless, I try to sever continuity with my forbears. Or is this a private rite of passage into a world where you can do anything to Shylock—kick, trip, spit, jeer—is this my form of unseemly mimicry?

But we are newlyweds, in unaccustomed spendthrift frivolity—prudence, like awareness itself, locked away.

When we arrive penniless in Belmont, I partly expect reprisal. No such thing. Portia must leave on urgent business for Venice. She invites us to be surrogate Lord and Lady of her house.

What ensues is an enchanting protection, a gilded safety. Here in Belmont, though, brief afternoon rests meant to restore bring me disquieting dreams. I seem to re-live my running away.

My father returns to his house. He has been robbed and abandoned by his only child. When he looks for support he is jeered in the streets.

In Belmont, my bridegroom and I evoke the lives of legendary lovers, their dangers and losses recede amid our distant music, “. . . In such a night . . .”

The enchanting leisure soon will end, but not until, through my playful expansiveness, companioned and protected, my father’s mirthless attempt at sociability in a frivolous world reveals itself further.

To my own contrite regret, through memories and disquieting, haunting dreams, I begin to see, as though for the first time, the circumscribed domain, unlived life: the merry bond is a despised stranger’s maladroit distortion of play.

The bizarre forfeiture provides a corporal power recognized by law. It will become a bastion of defense in a dismissive, isolating world, an obsession and sole companion. Shylock’s intractability will dwindle into the realm of caprice—like an aversion to bagpipes or a gaping pig. The forfeiture will become a sombre menacing device unmediated by provision for a surgeon’s remedy.

Intervention—the bond’s halting and annulment—will come as a relief. Shylock’s pleas to be recognized as human with eyes, affections, vulnerabilities like others remain unheeded, though not easily discarded.

His pain at my abandonment, his every connection to me is dismissed, his outcries jeered. Neither anguish nor corporal common denominator is admissible if you are Shylock.

Once I took something irreplaceable away from him—perhaps through an oblique rite of departure. Now I receive something of where he is, what he has been going through.

How, presiding for a time here in Belmont could I have expected anything beyond such good fortune or, in fact, avoided the melancholy of being newlywed without blessing? Not deserving it doesn’t eradicate the need.

A messenger from Venice, interrupting all reflection, announces Portia’s arrival. Portia will bring clarity. A distant music accompanies her. She is in dazzling array and knows about blessing. She will find a way. Portia will set things right.

Not so.

Portia is doing what she intended. She told Nerissa both prior to and just after the courtroom that their male disguises as judge and judge’s clerk will yield the fun of mistaken identities for their husbands to locate and unravel. The game of Portia’s devising, along with claiming-the-rings seems protracted. The audience knows what Bassanio must find out. It is Bassanio who is urged to credit his new bride with fortitude and the resourcefulness of saving the threatened day.

In this unfolding I find my mind wandering. I recall that nearly all of Portia’s scenes concern her hope within the strictures of her father’s legacy, to avoid the wrong bridegroom—a gentle, dark complexioned suitor would be such a one. No Desdemona she. Is she stranger-averse? After a socially familiar congenial Venetian wins her, the nuptials are disrupted by a threat to her bridegroom’s friend. Were her penalties impartial and just?

The lengthy uncovering of her role as Doctor of the Laws is an inescapable reminder of the fact of impersonation. She is a well-connected young woman with the motive of saving her husband’s friend from danger and also her marriage from implied tarnish. When Shylock asks of the “learned judge,” “Is that the Law?” his trust may seem ingenuous, naïve.

It hurts to come to a place of questioning my idealization of Portia, but increasingly it seems that she is at the verge of self-serving. Only human, perhaps, but where is the mercy unconstrained of which she spoke so beautifully?

She must enjoy the game she devises for Bassanio—at last from beginning to end her own terms—not her father’s will, not Shylock’s bond. But she has documents in hand, contents to impart.

Antonio’s ships, deemed lost, have with their merchandise reached safe harbor. Belmont’s is a seamless and convivial victory amid newlyweds, friend reunited with friend, dangers overcome, no losses, all efforts recompensed.

The adversary is vanquished, mission accomplished. The golden fleece is debt-free. Amid the bustle of victory, the formulaic comedy of caskets, riddles, and the wrong bridegroom averted is complete. The play, though, is not over.

Another of Portia’s documents, a legal one, is a deed of gift from “the Jew” of all he dies possessed with. I’m struck by a lapse into customary, casual designation—his on-pain-of-death conversion goes unacknowledged. And it seems he is under house arrest; one of the few actions available to him is, on command, to bequeath.

“Manna,” my husband calls this news. Not so to me. No question of refusal. My husband is a gentleman, we need the money. But this deed of gift for all Shylock dies possessed with suggests a death likely to come soon.

Emotions and questions are pried open and I feel their gravity without release. Did the penalty for intent go too far? Through her tutelage Portia has invoked a law so rusted with disuse that the Duke of Venice, himself, does not know of it—a law that weightily differentiates the value of citizens’ lives from those of aliens.

Does Shakespeare make use of religious conversion anywhere else? Notwithstanding the differences in time and values, no other examples come to mind.

Except for its financial provision, my husband takes no notice of the deed of gift. I manage to choke back “He did not choose you for his heir,” the first estrangement since my marriage. I begin to turn to poems and images as though they might offer a kind of companionship of their own. What I’m recalling is both painful and comforting, part of Emily Dickinson’s Success:

Not one of all the purple host

Who took the flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear of victory

As he defeated, dying,

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Break agonized and clear.

An image of my own forms itself in my mind: it’s as though there were the shadow of someone wounded, not dead yet, seen as a dragon, his strange regalia looted. Who can rejoice?

And I think now of The Ancient Mariner: “O wedding guest this soul hath been / Alone on a wide, wide sea . . .” Could this be a way of improvising, my way towards exploring the deed of gift?

I’ve wondered what Shylock’s hold on life might be, and what comes forth abruptly is that he has given up on us. No more entreaties, persuasions misplaced or urgently germane, to compel reckoning. That he has given up on us may confer a measure of near-death freedom. But is there a lonelier man?

Though it was compelled, he has provided for my husband and me. I wish I could say a simple thank you. Mine was a worse than brusque elopement. Now, if only in thought, a gentle, sombre farewell. I’ve come some steps since I misused your keys, your trust.

If I could retrieve your dead wife’s ring—my mother Leah’s ring—from an impulsive, shabby trade, I would. I may—though who can condone where you began—know something of what you’ve been through. Lender, provider, thank you. Be reckoned with. Solitary one, be comforted and not entirely alone.

The play seems to be scored for Shylock’s vanishing, but something else, something other, happens. Before Shylock leaves the courtroom, his voice, once urgent, once “fury and mire,” diminishes into numbed monosyllables: “I pray you give me leave to go from hence; / I am not well. Send the deed after me, / And I will sign it.”

He leaves in disgrace and returns after an entire act’s absence, a dozen or so lines before the close, in mention only; he is a mute provider, signator of the deed that Portia obtains, before she leaves Venice. It is as though he has been banished from the stage itself. Mysteriously, in absence and silence, awareness of him is sustained.

The relative triviality of the victors—once freed of obstacles—contributes toward the size of the defeat seeming larger than the size of the victory.

Feeling for the vanquished adversary clearly is not occasioned—deforming as his harsh socialization has been—by his personality, but through his plight. It occurs to me with the shock of simple truth that, at the close, Shylock is the only one who remains harmed.

Punishment for intent incurs for him not literal death but a version of annihilation.

A citizen of no country, the rialto no longer, what sort of home in the once familiar, however circumscribed ghetto, with its former shared worship, would a convert have? My own chosen conversion is an entirely different matter. His on-pain-of-death conversion is a spiritual intrusion, a damaging act of force, strangely named mercy.

Where, as his own time frame approaches the posthumous, and since the hereafter as he has conceived of it may be drastically altered, might this stranger deprived even of his strangeness turn?

Who cares?

No one in Belmont except for the spectator and—yes—Jessica who stands onstage and receives the part of the action that is for me a wordless event. And, beyond that I think that the tension, imbalance, outright discomfort one may feel at the end is Shakespeare’s gift to the witness.

Our longing has been stirred for the ideal of unconstrained mercy, spoken but not enacted on this stage. Perhaps, in its loftiness, it is beyond our quotidian lives. Might receiving with compassion the plight of one who has been harmed bring us a little further on the way towards the great ideal itself?

After the bond is annulled and the penalty of religious conversion for the alien’s intent is declared, Shylock’s absence becomes, until the play’s close, a subordinate theme or undersong. Is this a comedy’s way of transmuting what in Shakespeare’s tragedies has taken the form of an injured ghost?

The play’s actual music is background music, with the single exception of the lyric “Tell me where is fancy bred” that helps Bassanio to choose the winning casket. If the subordinate theme were expressed as melody, it might be, in Keats’ phrase, a “plaintive anthem.”

To experience the play as a whole is to include a dazzling heroine who is flawed and a selfless friend to her bridegroom who, before the bond, has kicked and spat at Shylock and later dispensed the penalty of enforced conversion.

At the close, it’s the disquieting adversary, Shylock, long after his intent is halted and annulled, who remains harmed and has a claim on our authentic concern and compassion.

The play has changed me; the play, itself, will help me locate my part.

All that’s formulaic pales before some central truth in the nature of things. I hope there’ll be some means to convey the event of receiving the last moments of the action.

I feel a personal connection with Auden’s direct way of describing what is humbling yet exalting: “In the deserts of the heart / Let the healing fountains start.”

I look towards where the entrances were from Venice and pause. Could it be that I, child of the ghetto, convert, wife to Lorenzo, living now in Belmont, transgressor and contrite penitent, onstage character and silent witness, have the honor of helping to carry the undersong?

Tomorrow, in rehearsal, our director will be a good companion in venturing into not quite familiar terrain. Now as I move towards rest and sleep I feel, through the sheer grace of theatre, an unmistakable joy.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

______________________________

Evelyn Hooven graduated from Mount Holyoke College and received her M.A. from Yale University, where she also studied at The Yale School of Drama. A member of the Dramatists’ Guild, she has had presentations of her verse dramas at several theatrical venues, including The Maxwell Anderson Playwrights Series in Greenwich, CT (after a state-wide competition) and The Poet’s Theatre in Cambridge, MA (result of a national competition). Her poems and translations from the French have appeared in ART TIMES, Chelsea, The Literary Review, THE SHOp: A Magazine of Poetry (in Ireland), The Tribeca Poetry Review, Vallum (in Montreal), and other journals, and her literary criticism in Oxford University’s Essays in Criticism.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast