by Pedro Blas González (January 2024)

But tell me, Victor, is life a game or is it only a distraction? —Miguel de Unamuno, Mist

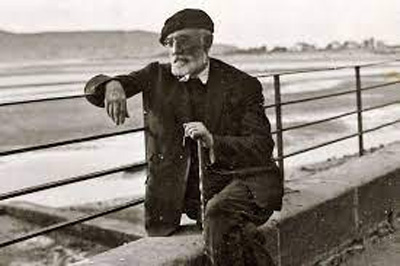

The Spanish writer and philosopher, Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936), does not mince words. To those who lack wisdom and courage, and pretend that life, the human condition as we know it, can be tamed by self-serving whims and fantasies, Unamuno must seem like a jester in the court of a mean and misanthropic king.

Naive intentions aside, Unamuno’s tough realism is a curious thing. Like Don Quijote and Sancho Panza, always on the prowl, often causing more trouble than they intend to, Unamuno stirs the imagination.

Existential philosophers are not thy brother’s keeper. People who follow the revealing/unrevealing dictate of truth do so at great personal peril. Life is not lived from an easy chair. Armed with the body armor of the senses and the lance of reason, the thinker launches himself at not so imaginary windmills. Unlike the errant Don Quijote, thoughtful thinkers separate the reality of ordinary inns from castles, carefully stretching the Ariadne’s thread that ties all things human to individual consciousness.

Existential philosophers are not thy brother’s keeper. People who follow the revealing/unrevealing dictate of truth do so at great personal peril. Life is not lived from an easy chair. Armed with the body armor of the senses and the lance of reason, the thinker launches himself at not so imaginary windmills. Unlike the errant Don Quijote, thoughtful thinkers separate the reality of ordinary inns from castles, carefully stretching the Ariadne’s thread that ties all things human to individual consciousness.

Like a bird of prey, Unamuno scouts and stabs at human reality. He challenges her in a proclamation of man’s quest to empower himself with the help of imagination. The Spanish author’s thought is vibrant, always busy separating reason and emotion, chalking up the respective victories attained by both sides. In the end…what is left—or is it merely always the starting-point? —there is man, solitary and unadorned by social-political restraints.

Nowhere in modern literature do we encounter a more poignant example of what Camus describes as the proto-first man. This is Unamuno’s concrete man of flesh and bones, a being tragically attuned to his differentiated life, existence always on the cusp of renewal and…eventual death.

Life is not the plaything of biologists, instead my life. How ‘I’ appropriate this – early in life – the greater chance I will have of personal fulfillment and the attainment and practice of personal autonomy. Unamuno is characteristically Spanish in at least one respect: he is a practical man. He is also stoic, embracing and sublimating difficulties on his own terms, an admirable character trait.

Unamuno’s outlook on the human condition respects reality, while safeguarding an intuitive will. This is a hint of where we ought to look first, if we believe Unamuno to be quarrelsome. The author of The Tragic Sense of Life, Mist and Abel Sánchez is a heroic poet in an age that cannot know tragedy. Following in the tradition of Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, it is next to impossible to be understood in a characterless age dominated by cardboard, politically-driven ideologues.

Like a latter-day Boethius in love with a mistress called philosophia, Unamuno is consoled by her. Philosophy becomes unbound again with Unamuno. She warns us against the hazards of life, the kind we encounter daily in the flesh, not the phantom, chimerical conjectures found in ‘theory,’ laboratories and textbooks.

Miguel de Unamuno seems irreverent to some—irascible, even— exasperating to others. This is the spirit of philosophy as embodied by one who knows that the self, man’s soul, is what is always at stake.

Mist: Life Lived from Within

For some people, God, like an umbrella, is a thing to be used. Utility may be a staple of human consciousness, but it is a killer of beauty.

Augusto, the idiosyncratic protagonist of Unamuno’s Mist (Niebla), walks out of his house, much as he walks within the confines of its walls, cocooned within himself. Setting out to the street “did not signify that he was taking possession of the external world; he was merely looking to see if it was raining.” Rain. City streets and umbrellas—even the sky—are all useful props for the exercise of the inner life. Thus, begins Unamuno’s existential novel Mist.

Augusto walks out of the security of his house reflecting on the nature of utility. He opens his umbrella, and momentarily, devoid of any place to go, waits for a dog to pass by and follows the animal. This is a portrait of a ridiculous man, some may think.

Taking one’s cue from a dog is a comedic literary device, many would agree. This is not unprecedented, though. Dogs are loyal, man’s best friend. Schopenhauer’s best friend was a dog. In Machado de Assis’s tragicomic novel Philosopher or Dog? a dog is more or less the protagonist.

Augusto makes a passing reference to a dog in order to follow it. Any direction will do: “And now in which direction shall I go?” he asks. Then: “I will wait until a dog passes and I will start out in the direction that he takes.” This becomes the impetus for his walk. A young woman passes by and, “as if drawn by a magnet, without knowing what he was doing,” he follows her instead.

Augusto’s early monologue is indicative of Unamuno’s distaste for the twentieth century. He reflects on the nature of utility vis-à-vis art, love, the invention of the automobile—the death of imagination and idleness.

Augusto’s early monologue is indicative of Unamuno’s distaste for the twentieth century. He reflects on the nature of utility vis-à-vis art, love, the invention of the automobile—the death of imagination and idleness.

Augusto’s world consists of leisurely walks and taking in the local atmosphere of the town. When an automobile passes by, he criticizes it as being noisy and kicking up dirt. For travelers, too, he has some choice words: “He who gives himself up to travel is never seeking the place that he is going to, but only fleeing from the place he has left.” This is typical Unamuno perspicuity.

We learn early in the novel that Augusto essentially lives his life in his own head. He tells us that the “most beautiful and noblest function of things” is that they should be contemplated.

We realize that the mist that the title of the novel conveys is an atmospheric condition as well as a place. Mist surrounds Augusto’s judgment of reality. Not that he cuts corners, for his grasp of reality is not a naïve one. His worldview is his and his alone. The Spanish thinker showcases his ideas on the nature of subjectivity and “yo-ism,” the author’s rendition of the subjective ‘I.’

Augusto seems ridiculous at times, silly at others, even makes perfect sense. He is his own man. He moves through the novel like one who is aware of the apparent unreality of the world and the human condition.

This is another example of mist (fog): the unreality of the world for a conscientious observer. The protagonist of Mist spends a lot of time reflecting on matters of life, death and love. His many monologues offer the reader a glimpse into his inner world, and Mist as an existential world.

Unamuno has written elsewhere that each individual encounters the world in proportion to his or her ability to do so. Temperament and imagination are central ingredients in his thought.

What makes the world and the human condition surreal has little to do with reality proper, but rather with our ability for self-reflection. Consider Augusto’s take on temperament: “Yes, all that men can do is to seek in the course of events, in the vicissitudes of their lot, nutriment for the sadness or joy with which they were born; and whether a thing is sad or joyful depends upon inborn disposition.”

What we call the world is Unamuno’s repository for human action and decision-making—intentionality, phenomenologists call this. Augusto, unlike Joaquín in Abel Sánchez, has a plan for his life.

Where commonplace beliefs vaguely assert that “experience is the greatest teacher,” Unamuno counters that in order to make sense of experience we must first possess a sense of our subjectivity. He tells us: “And if you are to love anything what is first necessary? To get a glimpse of it! A glimpse—behold, then, the intuition of love: a glimpse through the mist.”

Unamuno’s existential bluntness is like furniture we bump into in the night. We become irritated, wanting to kick it for having sharp, hard corners, and for being in our way.

Unamuno is literate, yet worldly. He is a poet, philosopher and philologist. His reading is extensive. His works enlightening and perspicuous. He spoke fourteen languages and is said to have learned Danish in order to read Kierkegaard.

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy in Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998). His most recent book is Philosophical Perspective on Cinema.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

Pedro: This was my introduction to Unamuno. I was enamored with your writing, became entranced instantly with your writing. I thank you. I am looking for a copy of MIST to begin with. “In the end…what is left—or is it merely always the starting-point?” For me this piece was the starting point. You have “stirred my imagination.”

Paul, thank you for your kind words.

Unamuno is a poet hard to classify.

In good will,

Pedro Blas Gonzalez