by Theodore Dalrymple (May 2020)

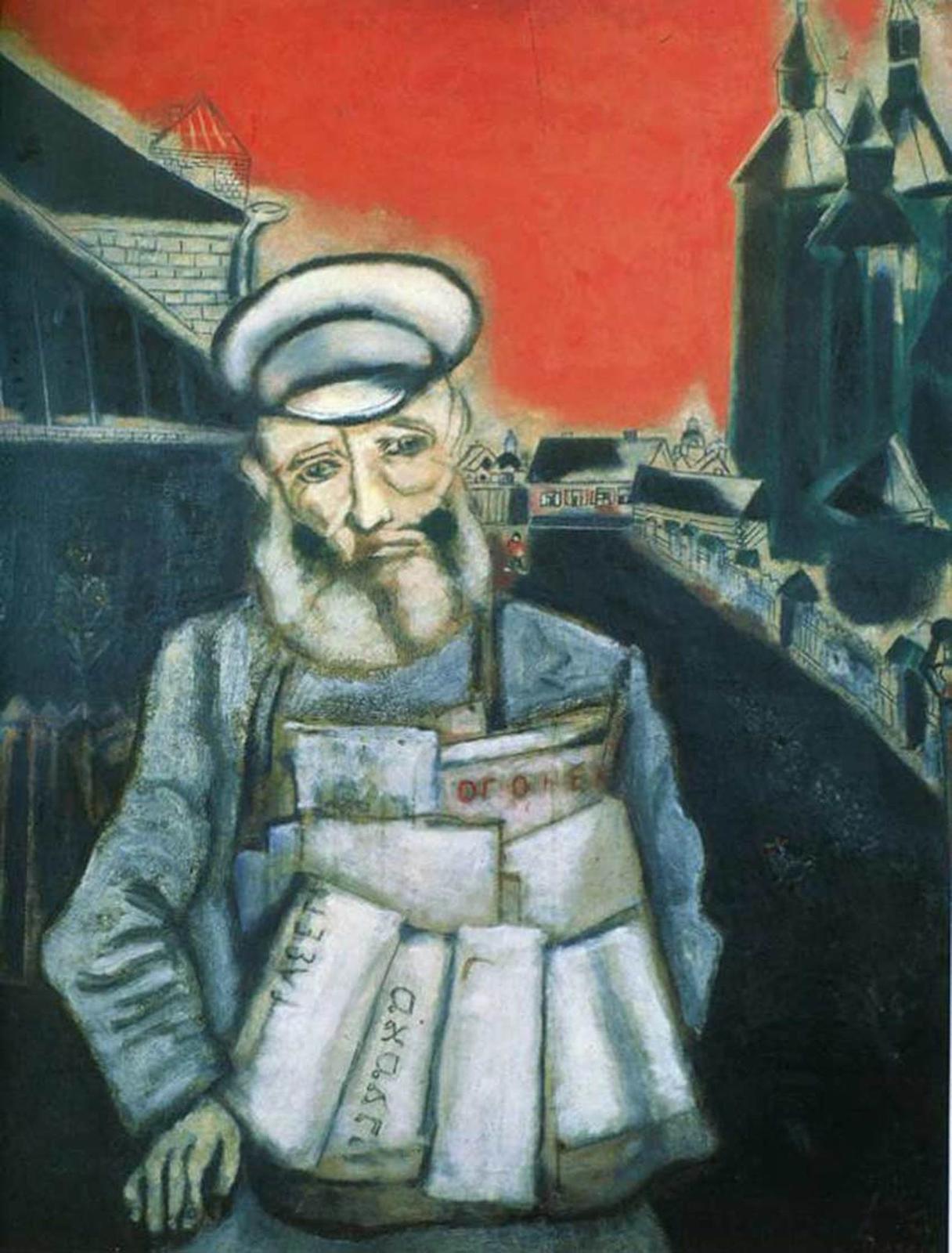

The Newspaper Seller, Marc Chagall, 1914

The introduction, by Henri Martineau, doctor, poet, literary critic and Stendhal scholar, to my edition of Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir, begins by stating that Stendhal was an avid reader of the Gazette des Tribuneaux, a journal that reported court proceedings. Stendhal believed that in this way he would be apprised of the actions to which the depths (or is it the heights?) of human emotion can lead. He was avid for sensation.

Ibsen also was a keen reader of newspapers, indeed during the second half of his life he read nothing else, except for the Bible. He kept himself informed in this way, even of medical matters. In his play, Ghosts, for example, the plot turns on whether the first manifestation of late-stage congenital syphilis can be mental deterioration, madness and dementia, and also whether syphilis can be transmitted to a child by a father alone. On both questions, Ibsen was right: though, with the disappearance of untreated syphilis and hence of congenital syphilis, even venereologists are uncertain of this. At the time Ibsen wrote the play, this was very recent medical knowledge (which has since disappeared), and it is probable that he became aware of it through the reading of newspapers.

Neither Stendhal nor Ibsen were idlers, still less were they fools. They may have enjoyed reading the press, but they clearly derived intellectual benefit from having done so. They turned their reading to account, but they were exceptional men. Even on the assumption that their reading of the newspapers was vital to them as inspiration to their literary productions, however, would their great literary productions be enough to justify the millions or billions of man-hours that people of their time spent unproductively reading the newspapers?

The amount of news available to us has increased exponentially since then. In Stendhal’s and Ibsen’s times (themselves separated by half a century), at least people had to seek out the news, that is to say make some kind of effort to obtain it; nowadays, it would take even more of an effort to avoid it. In other words, you do not go to the news, it comes to you, in taxis, airports, stations, and above all on telephones, whether or not you want it. You are, so to speak, compulsorily informed—or misinformed. At the very least you are likely receiving slanted information, since selection must be made among all the infinitely possible pieces of information you might receive. Not who guards the guardians is the question, but who selects the selectors? Stalin used to say that it was not the votes that counted, but who counted the votes; something similar might be said of the selectors of news.

The proliferation of sources of information might at first blush be thought to obviate the dangers of totalitarian control: there is no one and nothing at the centre of the spider’s web. There is no plot of the nature that the paranoid like to imagine. It is true that we are sent the kind of news stories on our phones (our chief source of news) that, historically, we have shown an interest in, and that only a few corporations have the powerful algorithms to preselect stories for us. If we have shown an interest in murders, murder stories is what we will get. But all we have to do to change our diet is to look at something else. We retain a degree of control, if we desire or choose to exercise it. It is not because junk food is available that we have to eat it.

A Swiss writer has just published (in English) a little squib exhorting us to cut ourselves off completely from the news, much as an alcoholic or drug addict is exhorted to abjure alcohol or heroin. The subtitle of Stop Reading the News is A Manifesto for a Happier, Calmer and Wiser Life. The author says that looking constantly at news is, or has become, as much an addiction as those to the aforementioned substances, and that the only cure is abstinence.

He outlines the charges against the consumption of news, at least in the forms in which so many of us now consume it. The news destroys our concentration and our ability to fix our attention on anything for more a few moments, making of our mind something akin to a minestrone or even to a velouté, simplifying everything and destroying all appreciation of priority and importance; in so far as news is overwhelmingly bad—for it is hardly news that someone’s house was not burgled yesterday—it causes us anxiety and makes the world seem more dangerous that in really is; it wastes our time because there is nothing useful we can do with the information provided, even if true, or true-ish, and we forget what we have read anyway; because selection is inevitable but not random, it makes us susceptible to manipulation and exploitation by advertisers and political entrepreneurs; by occupying our mental space and energy, so to speak, it reduced our understanding of the world we live in, which requires deeper knowledge and reflection.

With all this I have considerable sympathy—which is to say that I think it is largely true. I was once necessarily cut off from the news for several months—this admittedly was in the days before the internet and smartphone—as I travelled across Africa by public transport and, when I arrived back in what is known as civilisation, I discovered that the news had hardly changed and I had missed very little. What little I had missed, moreover, was hardly of importance to me personally: an armed conflict at the other end of the world, however bloody, does not cause me to lose a wink of sleep or affect my appetite in the slightest. I may regret it in an abstract way, and from a purely intellectual point of view wish that it had not happened; but in truth I am more affected by the illness of my pet than by the distant slaughter of thousands. As Dr Johnson said, public affairs vex no man.

And yet, at the same time, I feel there is something not entirely satisfactory about the author’s argument. He assumes that we can, and should, be interested only in that which affects us in a narrow, practical way, an in those things that we are able directly to influence (which are very few). In this connection I remember a joke told me by my late friend, Peter Bauer, who was a world-famous economist.

Two women, friends in their youth, meet again after a long interval. One has been happily married, and the other unhappily. The second asks the first how she manged to stay happily married for so long.

She replies, ‘It’s simple. I decide all the small things: what house we buy, where we go on holiday, how the children should be educated, what we should buy and eat. My husband decides all the important things: the interest rate and foreign policy.’

At the risk of being regarded as a monster of sexism, let me offer the following observation: when I call my distant brother, our conversation soon turns to public affairs and we hardly talk of anything others would consider personal; when my wife calls her distant sister, they never mention public affairs even in long conversations. I do not claim to know the causes of the difference between the conversations of men and women, but I have noticed that it is a pretty general one, though not universal.

Be that as it may, I found the use of one word in Mr Dobelli’s book disturbing, and that was relevant. He uses it in a free-floating way, as if something could be relevant without being relevant to anything in particular. But relevance is a relational term; what is relevant to a palaeontologist may not be relevant to a philatelist, and vice versa.

The author also uses the term to mean what is of immediate practical or emotional consequence to a person’s life. Quite apart from the fact that events over which one has no control may have a large practical effect on one’s daily life—for example, an increase in interest rates—it is a dispiriting view of the possibility of a rich and varied mental life that one’s attention should be fixed only on what is relevant to oneself in this narrow sense of the word. Indeed, one of the best ways to avoid depression of mood is to have interests that distract one from the day-to-day flux of one’s emotions, which are the borborygmi of the soul.

Mr Dobelli says— I think rightly—that the constant bombardment of the mind by a kaleidoscopically-changeable series of miscellaneous facts does not conduce to a deep understanding of the world and that it is better to study one thing, or a few things, in depth in order to achieve some higher level of understanding of the world. But the thing, or things, studied in depth need not be, perhaps ought not to be, relevant to the person’s life in any obvious utilitarian sense.

Not long ago, for example, I read a wonderful book titled Cuckoo, by Nick Davies. It was, as the title would suggest, about the common (though less and less common) cuckoo, on which the author was a world authority. This bird is of little relevance to my everyday life, though I like to hear it in the spring. If all the cuckoos in the world were to disappear, I could not honestly say that my life would be deeply affected, though in the abstract I do not relish the idea. I cannot truthfully say that I would lose my appetite or be unable to sleep over the disappearance.

Professor Davies has spent his life studying these birds, but I do not suppose that even he would claim that this was the most important subject of study possible, if the importance of the subject of study is to be measured by the number of people whose lives will be deeply affected by it. The study, on the contrary, is an end in itself because the creature is fascinating and it is delightful to know about its habits and behaviour. Great ingenuity has been expended on discovering information about the cuckoo, and I for one am glad of it, though I also gladly concede that the information is not relevant, in Mr Dobelli’s narrow sense, to my life.

O relevance, what crimes are committed in thy name! The education of many children has been vitiated utterly by the foolish demand of educationists that the education of children should be relevant to their daily existence and experience, when the whole purpose of education should be the broadening of their horizons, to alert them to the infinite beauty and fascination of the world, and not to enclose them in the world that they already know. How this broadening is to be achieved is the skill of teaching, which I do not possess myself; but children are not to be beaten or bored, rather they are to be inducted, into a liking of knowledge for its own sake. A person who desires to know for the pleasure of knowing is indeed fortunate, for he could live an infinite number of lives without ever experiencing the pointlessness of existence.

It is true that the constant consumption of snippets of news on telephones and by other means—floods in Bangladesh, a terrorist outrage in Amsterdam, the transfer of a footballer to Real Madrid, the arrival for talks in Moscow of the President of Outer Mongolia, the eruption of a volcano in Mexico, a Hollywood’s starlet’s nasty divorce, and so forth—is not a manifestation of a love of knowledge but rather of a thirst for distraction, and often for sensation. But the practical irrelevance of the information to a person’s life offered by this distraction is not the proper criticism of it; on the contrary, it is itself a manifestation of narrowness of mind.

Wisdom and knowledge are not the same thing, of course; an erudite man can be a fool, even in the field of his specialisation. But can a militant ignoramus, one who in principle despises knowledge that is of no relevance to his daily life, be wise? The demand for relevance in this narrow sense is a school for narcissism, self-regard and self-absorption.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Kenneth Francis) and Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast<

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link