by John Henry (May 2023)

L’Hémicycle de l’École des Beaux Arts (detail), Paul Delaroche, 1866

My father was a dedicated audiophile. He had hundreds of classical records (which I inherited and are now unfortunately melting in my garage!) He was a perfectionist. We drove to Switzerland from Turkey to buy a Revox reel to reel tape recorder. He recorded most of those albums and had a hand written index of it all. He taught me how to fastidiously clean the disc and needle, etc. He would take up his pipe, put on his Koss headphones and listen to his music while we were still asleep. We did not spend one day from grade school through high school without hearing Mozart, Liszt, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, et al. I loved the piano pieces. And then there was Rachmaninoff and Debussy. Wow.

Many years later I saw the Mozart dramatization “Amadeus” in the theater. It was several years after I had turned my musical interest towards the pop music of the 60s and centered on guitar centric bands like Cream, Hendrix, Mountain, and Ten Years After. The movie was quite moving on several levels. I was taken by one particular piece of the film compendium on a cassette tape I would play every morning on my way to work for months—Allegro con brio. It was absolutely energizing, sweet and sour, slow and fluid, sad to joyful, quickening finally back to the main theme in a plodding fashion. Thrilling and exhilarating. The oboe taking the melody, the strings following. Major to minor themes moving back and forth. Unrelentingly, Mozart touches nearly all our emotions in this piece.

Salieri’s very troubling lament was that the ‘monster’ had subsumed him to irrelevance, in spite of his faith in God. This is a great philosophical theme and adds a gravitas to much of the unfortunate silliness as portrayed by Tom Hulce. Salieri was older and had written prodigiously but Mozart’s work was more interesting and memorable. Possibly more complex and fresh, more exciting—and the public preferred it to Salieri’s. Mozart was a prodigy. His father pushed him to learn piano and compose at a young age. One of my favorite parts in the Hollywood movie was when Mozart asked Emperor Joseph II of his opinion on the piece he had just written and performed. It was ‘Chorus of the Janissaries.’ The king thought for a moment and replied: “Too many notes.” I almost fell out of my chair. There are similarities of a little too much in many artistic endeavors!

I would like to point out that in the late Renaissance through the Classical music epoch, most composers could not support themselves and relied on royal patronage. From Michelangelo to Mozart this was the case. In a way, this tended to limit their creative sensibilities. Likewise, architects now must rely on amply financed construction budgets offered by billionaire tycoons, corporations, trusts or royalty in order to engage in their wildest fantasies. (Rotating high rise, Dubai, Right)

I would like to point out that in the late Renaissance through the Classical music epoch, most composers could not support themselves and relied on royal patronage. From Michelangelo to Mozart this was the case. In a way, this tended to limit their creative sensibilities. Likewise, architects now must rely on amply financed construction budgets offered by billionaire tycoons, corporations, trusts or royalty in order to engage in their wildest fantasies. (Rotating high rise, Dubai, Right)

Many inventions are evolutions, based on combining two or more old ideas with a little extra added, and it can seem as if any art form or genre has its time before it matures and then stagnates and in worst case degenerates, sometimes because the combinations left seem contrived. —Christian Mathiesen

Consider how amazing it is that we live in an age where we have at our fingertips nearly every musical piece ever written via written score or multiple audio recording and performance, every work of literature, nearly every folio of art and photos of sculpture and architecture that we can ponder—without ever having to travel to experience the pieces in person. We have been able hear it all now for several years on a personal computer or smart phone. It was not so in Mozart’s time and technology did not allow music to be heard or moving images reproduced artificially until 1860 and 1890. Before that time music was played individually and heard only in cathedrals, music theaters, and in small assemblies. That was the primary entertainment/distraction of life that stirred the senses and evoked magic and imagination.

In 1962 to 1972, I finished grade school through high school between two military dependent schools in Izmir and Ankara, Turkey. We had no internet, telephone, television, cell phones, or even air conditioning until very late. Everything around us was foreign but we adapted. My brother and I had toys growing up ordered from Sears catalogs. I had a model railroad. And for culture we had classical music. We both started playing musical instruments and joined the school band. I played trumpet and then picked up guitar. Actually this scenario was not much different from living in the 1700s with only music available for entertainment. We did travel to nearby archaeological sites, as my father was keenly interested. I think exposure to Greek and Roman ruins and travels through Europe during the summers influenced me finally to make a choice between music and architecture and I selected the latter—due to the dubious future of a rock/pop music guitar player!

But through high school and a few years afterwards, before I became married, brought children into the world, and started working hard in my profession, I listened constantly to the music of the mid-60s through the mid-70s. I lost interest afterwards as the sound and soul changed quite dramatically and I had to concentrate on business matters.

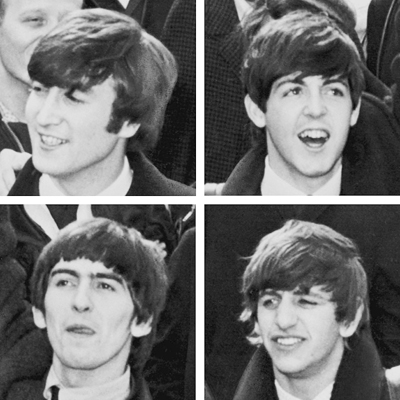

This morning I enjoyed a breakfast with an older friend who grew up just a few years earlier in the United States. On the loudspeakers over the open outdoor eating area classic Beatle tracks were being played. And so we started discussing music and the genius of the Beatles. We both agreed that the songwriting was unique for the time. Nothing sounded like the Beatles. There were copycat bands, yes. For years most aspiring guitarists and musicians had a difficult time replicating many of the songs in terms of chord structure and playability.

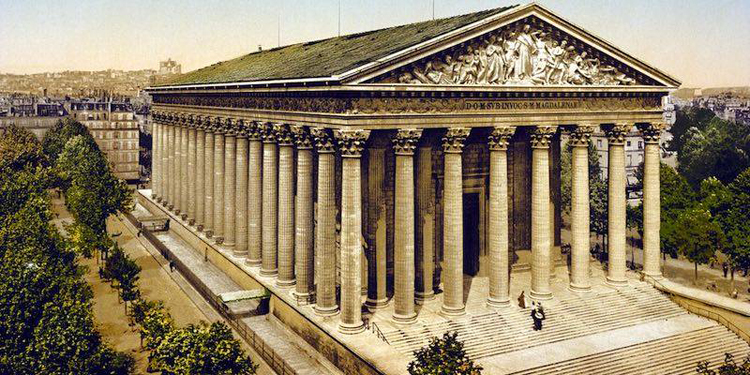

I remarked to my morning friend that many creative efforts are derivative and very few totally original. This was the case in architecture before the widespread use of reinforced concrete, steel and large areas of glazing—when it was entirely a study in masonry. In literature, painting and sculpture, through the Renaissance much was built upon works of previous masons and artisans. The Romans copied Greek temples and modified them to enclose them with brick to make meeting places instead of places of worship. Sculpture and painting followed likewise; much was replicated in style and technique. In 19th century Paris, the gigantic edifice La Madeleine (pictured above) was built in a Corinthian column style with extravagant entablature and sculpture in the pediment. This was derived entirely from ancient Greek temple styles. Palladio, in the mid-1600’s, adapted this style to residential structures for his Venetian clients.

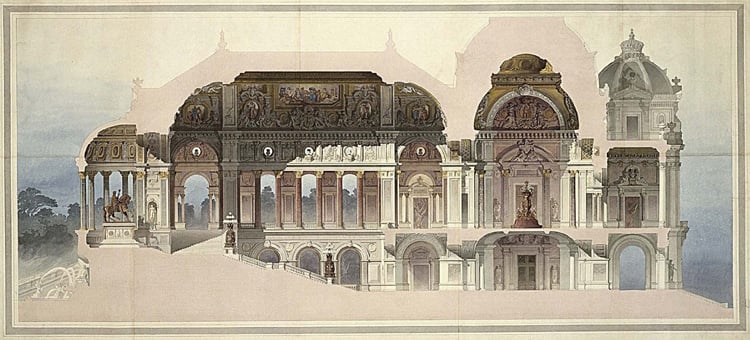

The idea of precedent on which to base creative design was taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, founded by Louis XIV in 1648. The students were asked to cite an earlier architectural work, most often from the Renaissance, on which they were tasked to create a new building and function. The charette results, executed by hand with tints still are breathtaking:

This method is no longer taught, rather the Bauhaus dictum as instructed by Gropius is generally followed: “Start from Zero,” which implies that your creative force is sufficient to create new architecture with the current materials and methods available. Form follows function. Obviously this lack of historical perspective has led to some very ugly architecture, streetscapes, and cities erected by practical minds and by simply educated minds.

Imagine going into medicine and not studying in detail the previous discoveries and general development as a result of clinical trials, vaccines, procedures, artificial valves, etc. Or starting a career as a mathematician, physicist, chemist, or biologist without examining the work of preceding generations and their theories and formulas?

It might be understandable in creative fields to force the young to think ‘laterally’ and not take into account routines that have been deemed to be repetitive and either not representing the current zeitgeist or taking full advantage of new technology and materials. In architecture, that could be an educational ploy to break out of tropes, yes. In painting, the surrealists, cubists, and impressionists definitely broke away from representative figure and landscape, but it was a long battle.

Salieri in a way represents the old guard of music previous to the work that Mozart foisted onto the public and for royal support and acclaim. Each generation seems to decry the debased work of the next. These analogies cannot always match each other. But consider hand work, technique, and time to execute classical music, art and architecture vs. modern. There is no comparison. There may be parallels in philosophy. Entire tomes of thought vs. today’s ‘just do it’ mentality.

Executing drawings for construction and erecting buildings by hand with rope and tackle vs. the use of computers and mechanized construction equipment results in an economically sensitive time difference, one which developers and bankers immediately seized when the Bauhaus gang decided to leave Europe and settle in the United States. What was lost was the delicate and meaningful culturally significant design of ancient art and architecture as interpreted by architects of succeeding generations (for ‘modern’ functions), transferred into marvelous stone and stucco edifices by artisans who cut masonry, ran profiles, bent iron, and painted exquisite representations of mythological and godly themes inside. The mechanical and computerized abstraction of form is now the cutting edge of architecture. Soon we will see the influence of AI in our streetscapes.

The idea of creating something novel has cache in many of the arts. A new generation has something they want to say to the world in their own way. Fine. An entire industry of art critics and educators embrace the new and eschew the old. This can be seen as liberalism vs. conservatism in the arts and education, a political narrative which supports and applauds every new ‘original’ statement and movement by individuals and groups. On top of the design alone, now we must consider carbon emissions, neighborhood implications, and of what color and gender the artist might be.

If there is a profit to be made in the most bizarre or incoherent designs (and music) the tendency is to take it to the limit and push things to a wild theatrical finale. And this is what architects and many musical acts did to differentiate themselves to a degree from the mid-60s through glam rock, heavy metal, and the likes of Madonna and Lady Gaga. (See Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Architect, Right)

Shock value in the arts turns heads. Even blasphemous. Woe be to those who copy, however. Copy the millennial historical past, copy the work done last week.

Musicians also tend to be stymied to create ‘original’ work. In some genres there is a direct lifting of entire musical phrases from earlier artists that is mixed in with a different rhythm and rap track for example. Musicians, for centuries, copied each other’s works and also created ‘covers’ in a complementary manner. The same is true in contemporary works.

Music invention, on the standard Western scale in one octave, consists of the manipulation of only 12 notes. Those notes can be doubled higher or lower. They can be played quickly (allegro) in many configurations or slowly (legato), or alternating tempo. Notes can be soft or loud; they can be short or held for several seconds. Where it gets interesting is which instruments play which notes and passages, and how can you combine a full orchestra to deliver the main theme.

Likewise an architect, especially in the 1700s, had a wonderful palette of geometry, repetition of elements, connection of details, and the integration of hand worked stone, iron, and plaster. The architect could evoke Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Italian and earlier French designs which added a cultural dimension. These qualities are not present in Modern Architecture. And there is no connection to human dimensions. Da Vinci gave us the Universal Man. Even Corbusier had a system of proportion. Columns and capitals are bodies and heads. Each ‘order’ has a set of rules and orders can be feminine or masculine. There is no order in today’s architecture and music.

That is not to say there is no creativity, it is just that quite often it is completely self-referential or a social or political statement—or something generated now by AI. See Kaktus Towers below. (Of course, the Left sees traditional architecture as a form of white supremacy and colonial repression, etc.)

If young musicians, architects, and artists are rather clueless about their craft, then they should look back in time to see what really worked well and what did not. Today’s architects and musicians believe that they can go straight into the studio or fire up their software and start playing notes or drawing lines on a computer thinking that something magical will happen. This is not how music, art, or architecture comes to be made.

The current schools of architecture start with a problem for which there should be developed a practical solution. The final form is simply the result of solving the problem (site constraints, function and budget) in a way that creates appropriate siting, exterior and interior circulation, and general function in terms of room layout and organization.

Architects copy from each other even in modern times. You often see the same bland and soulless structure in downtown high rises to strip malls and mid-rise offices. Current architectural thinking is that the modern way eliminates a forcing of function into a predetermined style—as those who practice Traditional or Classical Architecture are accused. But that is not quite correct.

Should buildings also look good as well as work well? Why is it only building design created after 1940 (in the International Style, to Modern, to Post Modern, to Deconstruction) considered more appropriate or superior to that historical tool box of arch, column, dome, and enveloping complementary detail built for 3,000 years before? Historical styled buildings employ nearly all modern methods of construction and high-tech electronics, HVAC, and synthetic materials used today.

Wright erased all vestiges of classical detailing from his early designs. He abhorred the cornice. Nearly all schools of architecture now, with the exception of Notre Dame and a school in Florida, have eviscerated the inculcation of traditional methods of design and construction from curricula. It is also quite rare to hear any tinge of classical music in today’s pop hits, but you get an occasional piano or orchestral splash.

Seventy five years after Rachmaninoff published his Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Opus 18 in 1900, contemporary composer Eric Carmen lifted the second movement for his hit “All By Myself”. When Mozart was in his prime, he was nearly the last categorized classical composer—a few years later Beethoven is said to have ended the period. Before Mozart there was Salieri, Bach, Haydn, Gluck, Handel, JS Bach, Teleman, Vivaldi and Monteverdi. Mozart had 150 years of music upon which he and his contemporaries based their melodies, tempo, and general compositional skills. Until more than 100 years later, composers were creating their musical pieces on paper by hand, pencil and ink. Entire works had to have each of the separate instruments’ parts conceived and executed in the imagination and typically on a piano without any automatic or mechanical means, just by hand. This was an onerous procedure which added to the tedious and laborious process of musical invention. Those who produced the most had to dedicate huge portions of their life to the invention and transcription of their musical genius by hand onto paper. Fortunately the Gutenberg invention allowed printing of the documents—the musical scores—for wide dissemination, as it did for literature and artistic drawings. Of course the publishers charged a small ransom for this service, similar to how music producers take advantage of contemporary artists.

Seventy five years after Rachmaninoff published his Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Opus 18 in 1900, contemporary composer Eric Carmen lifted the second movement for his hit “All By Myself”. When Mozart was in his prime, he was nearly the last categorized classical composer—a few years later Beethoven is said to have ended the period. Before Mozart there was Salieri, Bach, Haydn, Gluck, Handel, JS Bach, Teleman, Vivaldi and Monteverdi. Mozart had 150 years of music upon which he and his contemporaries based their melodies, tempo, and general compositional skills. Until more than 100 years later, composers were creating their musical pieces on paper by hand, pencil and ink. Entire works had to have each of the separate instruments’ parts conceived and executed in the imagination and typically on a piano without any automatic or mechanical means, just by hand. This was an onerous procedure which added to the tedious and laborious process of musical invention. Those who produced the most had to dedicate huge portions of their life to the invention and transcription of their musical genius by hand onto paper. Fortunately the Gutenberg invention allowed printing of the documents—the musical scores—for wide dissemination, as it did for literature and artistic drawings. Of course the publishers charged a small ransom for this service, similar to how music producers take advantage of contemporary artists.

My breakfast associate then mentioned if I’d known that the 60s hit by the Animals, “The House of the Rising Sun,” was actually based on the timing of the first waltz invention by the Viennese. Considered a scandal in that era (previous dances did not include much contact between the two parties), the music of the waltz is ¾ time: one two three, one two three, one two three, which is nearly identical to the Animals’ song. I followed that notion with the fact that Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple likened “Smoke on the Water” to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, upon which he apparently was inspired. Blackmore’s is a 7 to 10 note riff repeated over and over—an inversion of Beethoven’s introductory theme. Of course, Ludwig made more of it in his piece (approximately 35 minutes long engaging over 30 instruments) than Deep Purple (5 minutes, 41 seconds with vocals, electric guitar and bass, drums and organ). I would even deign to posit that Beethoven’s Fifth has some inspiration from Mozart’s Allegro con brio.

That morning, the Beatles hits kept playing in the background and it occurred to me that while classical musicians and even contemporary ones built many of their songs on previous compositions, the oeuvre of Lennon/McCartney did not quite follow that pattern. Much of rock, rock and roll, and its derivatives is formed on blues patterns which trace back to early American spirituals. Early Cream hits like Crossroads and many blues songs are Mississippi-based tunes recorded by Robert Johnson and others of the early 30s and 40s, primarily black musicians.

That morning, the Beatles hits kept playing in the background and it occurred to me that while classical musicians and even contemporary ones built many of their songs on previous compositions, the oeuvre of Lennon/McCartney did not quite follow that pattern. Much of rock, rock and roll, and its derivatives is formed on blues patterns which trace back to early American spirituals. Early Cream hits like Crossroads and many blues songs are Mississippi-based tunes recorded by Robert Johnson and others of the early 30s and 40s, primarily black musicians.

Many of the most famous classical and romantic era pieces are derived from folk songs. A particular turn or melody would be incorporated in larger pieces. Johannes Brahms based ‘Edward’ on a Scottish ballad. Bela Bartok’s ‘Three Rondos’ were taken from Hungarian peasant songs. And famously, Chopin incorporated the Mazurkas from Polish folk tunes.

Did the Beatles have any formal musical training? Lennon was able to create individual and unique compositions based on self-taught rhythms which led to creative improvisation. (Have you ever inquired of a classically trained musician to play extemporaneously? It is extremely rare for that to happen. They are trained to read music, not improvise much). Lennon’s mother taught him banjo chords and enrolled him in a local church choir where he did absorb how music was written/integrated and how a sense of harmony, pattern and repetition was generally conceived. McCartney played trumpet as a young lad but lost interest and then took up ‘skiffle,’ a type of folk music with jazz and blues nuances. Paul did study classical piano and guitar. George Harrison’s mother tuned into radio pieces on Sunday to “mystical sounds evoked by sitars and tables, hoping that the exotic music would bring peace and calm to the baby in the womb” (Wikipedia)

Unlike the composers of Renaissance, Classical, and Romantic pieces, early 60s pop groups had very little on which to base their music except for the songs they heard on radio or records of the 40s through the 50s, just twenty years of relevant material. Nearly all contemporary ‘pop’ musicians cannot read music nor write it on a staff. Moody Blues was an exception as they pioneered the development of ‘art rock’ and ‘progressive rock’ with their 1967 album ‘Days of Future Past.’ The fusion of classical music in their work is most apparent. Of more contemporary times, Miles Davis and Lady Gaga both had formal music studies.

Unlike much classical music where one can find a turn or phrase that was used by a previous generation or contemporary musician, the music of the Beatles seems to have had no previous origin. If you start thinking about the most obtuse songs like “The Walrus” or “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” there seems to be little or no reference to previous musical genres. The Beatles, like the early classical composers, spent enormous amounts of time at their craft. In Hamburg, where the Fab Four cut their teeth, they would play daily 6-to-10-hour gigs in the bars and underground dance taverns. Through the sheer volume of playing in their formative years, they were able to create a series of completely original songs that thrilled their listeners.

“The Beatles wrote about 230 songs in 11 years, or about 21 pieces a year.” (Quora) So… two songwriters wrote 10 songs each a year with side contributions from Harrison and Starr. Now these songs are typically two to three minutes each. Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 was nearly 60 minutes long in its original form. The six Brandenburg Concertos varied between 10 and 23 minutes each and involved 17 instruments. Mozart wrote over 600 pieces in his lifetime, JS Bach wrote over 1,000! The difference in effort and circumstance between those writing previous to the industrial revolution and contemporary artists in our modern age is astonishing, especially considering that musicians now have the advantage of recording studios where they can create and test their compositions endlessly.

The early Beatles were simply two guitars, bass and drums. They claimed they wrote for their fans initially and then for themselves. Their producer George Martin was classically trained, and you can hear his influence on many of their mid to later works which include traditional instrumentation and composition even: “Eleanor Rigby,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” and “A Day in the Life.” This connection added a fantastic depth to the collaboration with Lennon/McCartney. The classical connection was a transcendent component that was mimicked by other pop musician contemporaries. It elevated the quality and status of the music of the Beatles.

While we can hum passages and the main themes of many classical and romantic composers, the music of the Beatles was supremely inventive and a stand alone in the midst of their contemporaries. Their short compositions can be recalled from beginning to end. They weren’t derivative, except in a very few instances. They were virulent individualists. Their music is timeless in many respects.

While we can hum passages and the main themes of many classical and romantic composers, the music of the Beatles was supremely inventive and a stand alone in the midst of their contemporaries. Their short compositions can be recalled from beginning to end. They weren’t derivative, except in a very few instances. They were virulent individualists. Their music is timeless in many respects.

Now, artificial intelligence is promising a new style of music but it is completely derivative as it has to ‘scrape’ the scores of all previously published compositions to come up with something new and listenable. Hearing early attempts of computer-generated music, and the failure of AI to come up with any type of humorous joke, the conclusion can only be that emotion and creativity of the human soul as translated by various instruments and single or multiple vocals will reign supreme over any software program or machine that tries to write emotively in such a sublime medium.

Table of Contents

John Henry is based in Orlando, Florida. He holds a Bachelor of Environmental Design and Master of Architecture from Texas A&M University. He spent his early childhood through high school in Greece and Turkey, traveling in Europe—impressed by the ruins of Greek and Roman cities and temples, old irregular Medieval streets, and classical urban palaces and country villas. His Modernist formal education was a basis for functional, technically proficient, yet beautiful buildings. His website is Commercial Web Residential Web.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link