By John Broening (June 2018)

“Private faces in public places are wiser and nicer/Than public faces in private places,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1932, when he dedicated his verse play The Orators to his friend and fellow poet Stephen Spender. During the era in which Auden imagined those lines, there was a clear demarcation, if not an unbridgeable gap, between the public and private. Gentlemen dressed impersonally in suits and bowler hats every day and left calling cards. The famed English reserve and politeness had a territorial quality at its center, as an outsider (John Updike) would later point out, but it was nonetheless all but impenetrable. Public officials spoke in a formal if not lofty tone that displayed their training in classical rhetoric. It was an event when the Prime Minister smiled; it would have been unthinkable at the time that he would discuss his personal wounds or his difficult and loveless upbringing (and all prime ministers had been shipped off at a tender age to public schools and had suffered the alarming and routine abuse that was part of the acculturation process).

The private virtues that Auden had in mind were sincerity, warmth, passion, honesty and empathy, virtues that public figures at that time rarely even thought to broadcast. The public faces, it followed, displayed insincerity, coldness, dissembling, and what Auden liked to call “the rhetorician’s lie.”

Auden was also signaling something to his dedicatee, something he could say only in coded, if not private, language. The dedicatee, Stephen Spender, shared something else with Auden, a knack for chasing working class boys: that “public place” that Auden had in mind was likely a louche bar, or worse and that “private face” had a very specific objective on its mind.

Nowadays, at a superficial glance, it seems as if Auden, who in his personal life was a singular combination of the chaotically informal and the papal, would have been happy with the current state of affairs. There are a multitude of private faces in public places: from Jimmy Carter onwards, our presidents have felt the need to broadcast their compassion, their ability to suffer and come out redeemed, their warmth, their shirtsleeve down-to-earthiness, even (in Carter’s case) the lust they felt in their hearts in the presence of attractive women other than their wives. The personal note that began to creep into the interview with the statesman has transformed that interview into nothing but personal notes.

And lower down the ladder of power, the private face has made itself at home in the public place, loudly sharing intimate details on its cell for everyone within earshot to share, wearing its laundry day clothes every day of the week, eating and drinking with an admirable lumpen unselfconsciousness that Rousseau would have approved of, treating the entire world as its living room.

As the classical scholar and cultural critic Daniel Mendelsohn has pointed out, apropos of our unrestrained use of smartphones in public places, the word “idiot” derives from the Greek word for “private,” and an idiot is someone who cannot distinguish between public and private arenas.

In the world of literature, the private face has dominated the public space for some time now. What is called either the personal memoir, or misery lit, or—my favorite—autopathography, has become the defining genre of our time.

An autopathography is literally a work about one’s own illness: an autobiography that tells the story of one’s own addiction, mental illness, self-destructive behavior or abuse at the hands of another.

Autopathography can be about addiction to alcohol (Happy Hours, Dry), pills (Pillhead), heroin (Permanent Midnight) or meth (Tweaked). There are also misery-lit memoirs on anorexia (Wasted), depression (Prozac Nation), bipolar disorder (An Unquiet Mind) and sex addiction (Love Sick, The Surrender).

Misery lit is everywhere these days. It has even infiltrated other well-established genres. It has been grafted onto the celebrity memoir and become a way for the lightweight celebrity to give himself or herself some gravitas (Marie Osmond’s and Brooke Shields’ memoirs on postpartum depression); for the sports star to add some intriguing darkness to his corporate-friendly persona (Open, by Andre Agassi); for the politician to add a little humanity and rehabilitate himself (Jim McGreevey’s coming- out memoir, The Confession).

It has also attached itself to the racial-consciousness memoir (Hung: A Meditation on the Measure of Black Men in America, by Scott Poulson-Bryant) and the foreign-correspondent memoir (Hello to All That: A Memoir of War, Zoloft and Peace, by John Falk), even to cookbooks. In the introduction to Damn Good Food, Mitch Omer’s collaborator writes of Chef Omer’s sexual promiscuity, his bipolar disorder and his alcoholism: We had to schedule work on this book around his second round in rehab and a court-ordered stint for driving under the influence, which he served in a Pine City, Minn., jail.

In its elevation of the ordinary, its rejection of traditional privacies, its obsession with pathology, its exhibitionism masquerading as healing, and its score-settling masquerading as honesty, misery lit strongly resembles another popular contemporary form: reality TV.

Like reality TV, misery lit spares no detail. Its violations of decorum, its assault on its subjects’ innermost secrets are somehow a proof of its authenticity.

Its routine invasions of privacy are justified by misery-lit authors as being, “I don’t know, like, therapeutic.” (Lance Bass, formerly of ‘N Sync, about his coming-out memoir), or therapeutic’s New Age twin, “liberating,” (Toni Bentley, on her sexually explicit memoir, The Surrender).

The somewhat dubious therapeutic value of misery-lit memoirs is offset by other considerations. “Writers are always selling somebody out,” Joan Didion famously remarked, and nowhere is this cynical precept more often brought home than in the response to these precocious autobiographies.

In recent years, numerous memoirs have been attacked by some of their subjects as being not just untruthful but cruel and exploitative. Witness Augusten Burroughs, Julie Myerson, even Martin Amis. Significant chunks of Amis’ precocious memoir Experience were devoted to the writer’s fatuous musings on the ghastly fate of his cousin Lucy Parrington, who was tortured and killed by the British serial murderer Frederick West (“When I think of Lucy being bound or restrained my nerves and membranes feel her moral force and its demand for release . . .”).

In recent years, numerous memoirs have been attacked by some of their subjects as being not just untruthful but cruel and exploitative. Witness Augusten Burroughs, Julie Myerson, even Martin Amis. Significant chunks of Amis’ precocious memoir Experience were devoted to the writer’s fatuous musings on the ghastly fate of his cousin Lucy Parrington, who was tortured and killed by the British serial murderer Frederick West (“When I think of Lucy being bound or restrained my nerves and membranes feel her moral force and its demand for release . . .”).

Unsurprisingly, after Experience was published, Lucy Parrington’s relatives announced that Amis had barely known her and was exploiting her fate to sell his book.

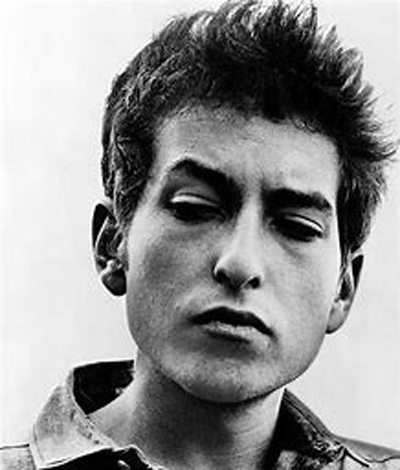

Widespread cultural change often originates in unlikely places. For example, when Bob Dylan started his career, he began by parroting an aesthetic that he’d picked up from the ethnomusicologists who had inspired the folk movement: Harry Smith and John Lomax, and Lomax’s son Alan. The aesthetic prized authenticity above all else, the music of field hands, tenant farmers, Carnies, convicts, former slaves above the music of professionals who had offices in New York City; before the Beats, before the hippies it valued the rough-hewn over the unpolished, the simple over the complicated, the sincere over the epigrammatic, the eccentrically distinctive over the well-made prototype and the demotic over the bourgeois. It explained why Dylan, a nice middle- class boy gave himself a made-up biography in which he rode the rails with hobos and grew up jamming with old bluesmen. It explained why the two Lomaxes, when they took Leadbelly, a former convict and their greatest discovery, on tour, they forbade him to sing the standards he wanted to sing and insisted he sing the field songs and prison songs that he was heartily sick of. It explained Dylan’s ragged, adenoidal singing, his hectic and formless harmonica playing and his harsh guitar strumming. Dylan, to his credit, soon outgrew this stance, and was capable of turning out polished, well-made songs like “Tonight I’ll be Staying here with you.” But he had popularized an aesthetic that would touch everything from manners to fashion to food to furniture to politics.

Widespread cultural change often originates in unlikely places. For example, when Bob Dylan started his career, he began by parroting an aesthetic that he’d picked up from the ethnomusicologists who had inspired the folk movement: Harry Smith and John Lomax, and Lomax’s son Alan. The aesthetic prized authenticity above all else, the music of field hands, tenant farmers, Carnies, convicts, former slaves above the music of professionals who had offices in New York City; before the Beats, before the hippies it valued the rough-hewn over the unpolished, the simple over the complicated, the sincere over the epigrammatic, the eccentrically distinctive over the well-made prototype and the demotic over the bourgeois. It explained why Dylan, a nice middle- class boy gave himself a made-up biography in which he rode the rails with hobos and grew up jamming with old bluesmen. It explained why the two Lomaxes, when they took Leadbelly, a former convict and their greatest discovery, on tour, they forbade him to sing the standards he wanted to sing and insisted he sing the field songs and prison songs that he was heartily sick of. It explained Dylan’s ragged, adenoidal singing, his hectic and formless harmonica playing and his harsh guitar strumming. Dylan, to his credit, soon outgrew this stance, and was capable of turning out polished, well-made songs like “Tonight I’ll be Staying here with you.” But he had popularized an aesthetic that would touch everything from manners to fashion to food to furniture to politics.

Similarly, almost 40 years ago, the autopathography movement arose not from a prose memoir but around, of all things, a collection of sonnets.

Similarly, almost 40 years ago, the autopathography movement arose not from a prose memoir but around, of all things, a collection of sonnets.

In America, misery lit has a distinguished pedigree in the realm of poetry. The works of poets John Berryman, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath and, above all, Robert Lowell, drew on their struggles with mental illness and on intimate details of their own lives for their material.

There was perhaps something prophetic about the confessional work of these mad poets. The psychologist R.D. Laing saw the insane as the canaries in the cultural coal mine; he believed that they displayed pathologies that would soon manifest themselves in the culture at large.

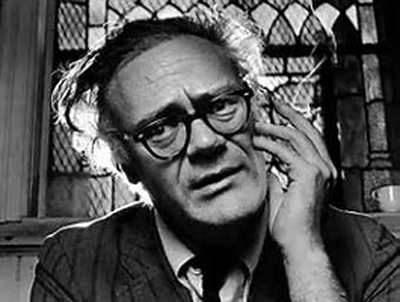

For example, when Lowell published his sonnet sequence The Dolphin (1973), which described his own mental breakdown and quoted from letters and private conversations with his ex-wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, and his current wife, Caroline Blackwood, his approach was still a novelty.

“Yet, why not say what happened,” was the rationale given by Lowell in his poem, “Epilogue.” His critics weren’t so sure.

Not knowing she was witnessing the glorious birth of a new genre, Adrienne Rich, a fellow poet and former friend, wrote: “What does one say about a poet who, having left his wife and daughter for another marriage, then titles a book with their names, and goes on to appropriate his ex-wife’s letters  written under the stress and pain of desertion, into a book of poems nominally addressed to the new wife? This is . . . a poor excuse for a cruel and shallow book, presumptuous (in balancing) injury done to others with injury done to (oneself).”

written under the stress and pain of desertion, into a book of poems nominally addressed to the new wife? This is . . . a poor excuse for a cruel and shallow book, presumptuous (in balancing) injury done to others with injury done to (oneself).”

Rich’s attack resonates with questions that are even more relevant today: Does the posture of total frankness hide aggressiveness toward others and a destructive narcissism? Does the need for self-revelation and self-display always trump the need for privacy?

And, just as importantly, are we benefited by revealing our own secrets? Joe Orton, the playwright, was one of the brilliant Lords of Misrule that the Sixties produced in such abundance, a talent whose Wildean wit was always pointed towards the subversive. But even he recognized early on the downside of confessionalism. In his play “The Ruffian on the Stair” (with typical Ortonian perversity, the title is taken from a poem by Henley, that stuffy Victorian poet), a character makes a devastating confession:

The number of humiliating admissions I’ve made, you’d think it would draw me closer to somebody. But it doesn’t.

And Orton the playwright recognized something else about the urge to confess one’s secrets: its theatricality. Rather than being a hallmark of authenticity, it seemed like the opposite. If the public faces in private places of Auden’s time were characterized by pomposity, those of our time were marked by the theatrical nature of constant self-revelation.

In Paul Theroux short story The Exile, the narrator, an attaché at the American embassy in London, describes the famous American confessional poet Walter Van Bellamy, a thinly veiled representation of Robert Lowell. Bellamy’s poems are “spidery monologues about his domestic affairs.” They are intimate, “but paradoxically so intimate it gives nothing away, so private it sounds anonymous.” And Lowell—or Bellamy—the man is similar: seen, from a distance, on stage, he radiates an aura of warmth and generosity; seen up close he appears cold, shifty, and supremely uninterested in his fellow human beings.

Similarly, in his wicked contemporary memoir, Difficult Women, her former close friend David Plante reveals that Germaine Greer would hold forth to a room of strangers about her drawn-out battles with her mother and but, one on one, would not discuss personal matters.

Similarly, in his wicked contemporary memoir, Difficult Women, her former close friend David Plante reveals that Germaine Greer would hold forth to a room of strangers about her drawn-out battles with her mother and but, one on one, would not discuss personal matters.

Though some cultural critics, chief among them David Shields, have declared that the novel is a spent literary form and the authentic contemporary genre is autobiographical writing, the truth is that the theatricality of confessionalism is paralleled by the artificiality of its literary expression: most memoirs have the same basic structure, the same conventions derived from both the 12-step movement and a watered-down Christianity, the same arc of bottoming out, followed by redemption.

And there has been no greater cheerleader for the memoir than The New York Times, where the memoir rules not just the book review pages, but the Sunday column “Modern Love.” Even the style of the cultural pages is marked by the example of the memoir: the embarrassing and often gratuitous personal anecdote, the tone of forced intimacy, the lavish use of the first-person pronoun.

However: there are exceptions to this, memoirs that are relentlessly revelatory and naked but also marked by an awareness that personal unhappiness has a source in forces greater than the thin truths of the self.

The confessional revolution has taken place alongside two other revolutions that have upended our sense of what is public and what is private:

The first is the rise of social media, computer-maintained instantaneous communication and networking systems that, if not obliterate, at least make hazy, the old distinctions between public and private.

Facebook, for example. Is it public or private? Are our communications to our Facebook friends privileged? Can we safely use it to vent about a tyrannical boss or express a borderline seditious political opinion? And conversely, do we use it to break up with people, to quit jobs, to express our love for someone in the cyber-presence a small public crowd? Does it—and Twitter and Instagram—make the public private and the private public?

And as Andrew Keen has pointed out, it should be called anti-social media: Facebook is a paradise for the passive-aggressive: we can maliciously gossip to one friend about the online postings of another; we can unfollow a friend so they go on posting about the organic meal they cooked at home or the Dave Matthews concert they attended, blithely unaware that we’ve stopped listening to their uninteresting outpourings; and best of all, we can unfriend them with their noticing, at least for a little while.

The second revolution that has upended our sense of what is public and private is the revolution in surveillance: drones, remote telephone monitoring devices, small self-propelled aerial cameras, facial recognition software and spyware, software which is used mostly for tracking internet users’ habits and the drastic curtailment of civil liberties that has happened since 9/11, a curtailment that is remarkable also for the lack of public protest it engendered, a lack of protest enabled by our enfeebled sense of the value of our own privacy.

And the increasing use of surveillance technology has not just happened at a macro level: a CCTV system that can be operated from a laptop or cellphone is now financially within reach of any homeowner or small business owner. And even smartphones can double as surveillance systems.

All three of these trends—the trend towards confessionalism, the rise of social media, and the increasing use of surveillance technology, are not just interconnected but mutually reinforcing. The bargain that reality TV participants make is the same one that we make every time we use social media: a degree of public exposure in exchange for the loss of privacy, and often, the loss of dignity (being famous for 15 minutes doesn’t quite describe the state of affairs any more: the developing world has microcredit; we have microcelebrities). Often, surveillance technology is used to create social media stars of a sort: the mom who freaks out at a drive-through pickup window, the drunk idiot caught dancing unawares. And the bread and butter of social media (and increasingly, the enfeebled traditional media) is often the bottomlessly trivial doings of reality TV stars: what they tweeted, their latest selfie, their feud with another reality TV star. If it’s a slow news day (as it is today as I write this), one of the lead stories might even be the revelation that a reality star has struggled with an eating disorder or that she was sexually abused as a child.

Some of these trends, like the increasing use of surveillance technologies, are trends that we have little control over. Others—how often we use social media, how much of our personal lives we choose to share with the world at large, are behaviors we appear to have near complete control over. But can we, do we, really have control over them? As Marshall McLuhan said, “First we create the machines, then they create us.”

I am a cultural conservative. What this means is that, when I am confronted with the confusion and ugliness of modern life, my first instinct is to look to the past for answers as well as for comfort, specifically, because I was trained as a literary critic, towards the Anglophone literature of the last 150 years: Henry James’s fiction, Eliot’s poetry and literary criticism, Matthew Arnold’s poetry, above all his lament to the unexpressed and unexplored, The Buried Life. How did our ancestors in the pre-confessional age regard the contrasting needs for privacy and self-expression or self-revelation and, as we like to say today, how did they deal with, how did they process trauma, unhappiness, madness, secrets and scandal? I examine two Victorian trials, the divorce proceedings of the Irish patriot Parnell and the more famous trial(s) of Oscar Wilde. In the pre-confessional age, often the only way the public would gain a glimpse of the private lives of the living famous was in the wake of a civil or criminal trial. I examine the sad story of the suicide of Henry Adams’s talented, disturbed wife Clover, and its absence from Adams’s classic Autobiography. I look at the now-discarded idea of the Open Secret and the way it played out in the lives of Noel Coward, Franklin Roosevelt, JFK, and Susan Sontag.

Finally, I examine the literature of dystopia, including not just the obvious choices 1984, Brave New World and Philip Dick’s science fiction but the little-known fantasy writings of Primo Levi.

One of the central themes of science fiction, which is of course as much about the present as the future, is the struggle between a centralized, technologically energized power structure and the autonomy and privacy of the individual.

_________________________________

John Broening is a freelance writer based in Denver, Colorado. His writing has appeared in Gastronomica, Departures, The Baltimore Sun, The City Paper, The Faster Times and The Outlet and his article on the Noble Swine Supper Club was featured in Best Food Writing 2012.

More by John Broening.

Follow NER on Twitter at @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link