by Norman Berdichevsky (November 2017)

Within the space of a week, referenda to determine the question of national independence took place in Kurdistan (see NER September 2017) and Catalunya. Both of these two issues are just being made felt in a world already full of ethnic and religious conflicts and disputed border regions, yet they have been given little recognition by most media reporting that prefers to focus on the responsible central government authorities in the national capitals of Baghdad (Iraq) and Madrid (Spain), both of which expressed total opposition.

There are a number of glaring differences between these two issues but in each case, it is clear that they threaten what is not just a fragile relationship between neighbors, but the upsetting of traditional alliances as well as the involvement of outside powers. Press coverage of the participation and the division between yes/no votes were accurately reported in Kurdistan where approximately 90% voted yes for independence with a very high turnout of more than 80% whereas in Catalunya the 90% yes majority turns out to have been a so called “majority” only of those who voted, constituting less than 45% of the eligible voters, i.e., a non-“majority” of about 35%, an equally poor result of the one obtained in the previous illegal referendum of 2015).

Moreover, the Kurdish population of Iraq is heavily concentrated in the Kurdish region but almost entirely absent in the remainder of the country, whereas in Catalunya, a large percentage of the resident population is not Catalan but consists of Spaniards from other regions who have sought work and eventually settled there in what is the most prosperous and dynamic region of the country. In addition, may Catalans live and work in other regions of Spain. By contrast, Kurdistan is landlocked and surrounded by three hostile powers, Iran, Iraq and Turkey that have done everything in their power to threaten the Kurds.

The case of Catalunya, like that of Scotland, is much more intricate and meshed with the neighboring more powerful rival state. Both regions were absorbed into a major European state that expanded to become a world power. Both have therefore perplexed many observers. In Ireland and Scotland, local nationalisms are not entwined with the cultivation of a separate language, Yet their nationalisms challenged English rule to free themselves from serving the British empire.

The “national language” is spoken by a tiny dispersed, rural population or is used purely as cosmetic dressing for show along with old folk festivals. First language speakers of Irish Gaelic (also known as Erse) and Gaelic are found only in the most remote and rural areas and barely account for 1% of the populations. In Wales, there is an active Welsh speaking population of close to 20% almost all of whom are also fluent in English. In the Kurdish areas of their heartland in present day Northern Iraq as well as Iran and Turkey, there is strong sympathy for the cause of an independent homeland but major difference in local dialects makes mutual understanding very problematic.

Only in Catalunya is there a very intimate correspondence between a true sense of national identity with fluency in the original and ancestral language confirming what German philosopher Johan Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803) wrote (On the Origin of Speech, 1772. Uber den Ursprung der Sprache). He wrote: “Has a nationality anything dearer than the speech of the fathers? In its speech resides its whole thought domain, its traditions, religion and basis of life, all its heart and soul . . . With language, the heart of a people is created.”

It is for this reason that the Catalans have maintained such a fierce sense of pride and opposition to the concept that they must regard themselves first and foremost as “Spaniards” because they are citizens of Spain. It is understandable that in their own homeland they should have priority status. Catalans take great pride in their illustrious artists and painters such as Gaudí and Dalí and resent foreigners referring to them simply as “Spaniards”.

The issue of Catalan separatism once again threatens the unity of the country, a close NATO ally. It further constitutes a divisive invitation to Muslim extremists who wish to add fuel to the fire of a jihadist crusade determined to reverse the Christian “Reconquista” and win back the territory of the entire Iberian peninsula for the ummah as ISIS pledged, true to its vision of an all embracing Caliphate. This was reiterated by El Qaida and other extremist groups after the van attack in Barcelona on Las Ramblas thoroughfare which left 13 people dead. In a propaganda video, an ISIS member described the Barcelona perpetrators as “our brothers,” while another threatened “Spanish Christians” and promises to return the country to the “Land of the Caliphate.”

The Historical Divide of Language, Geographic Orientation, Economy, Social Mores, and History

As early as the twelfth century, Catalan balladeer-poets, or troubadours, wandered through the region and northward into Provence at a time when the language spoken there was recognized as a Catalan dialect. This vibrant poetic tradition and the use of Catalan by philosophers and historians, the greater achievements of Catalan seafarers and merchants who travelled throughout the Mediterranean and brought their language to Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily and traded with the Orient at a time when Spain still had no overseas experience, colonies or trans-Atlantic ties. This heritage has, for many generations, contributed to the feeling that a noble and civilized culture had been submerged by Castile, the central region located on the meseta (upland) that led the struggle against the Muslims from the 9th to the 15th centuries.

Catalans regarded Castile as a region that had remained under Arab Muslim rule for much longer and absorbed a tradition, and character traits that deviated considerably from their own much more commercial, literate, cosmopolitan, sophisticated, and “tolerant nature.” Recently, the city council of Barcelona and the regional parliament both passed regulations against bullfighting, long regarded as a primitive Castilian tradition.

Barcelona, rather than Madrid, became the engine of change, progress, industrialization, workers’ unions, the first railways and the first opera. In Castile, the old prejudices against merchants and working with one’s hands still prevailed among an elite out of touch with new developments. Arch-conservatives distrustful of Catalan commercial astuteness even labeled support for the Republic during the Civil War (1936-39) part of what they called a “Judeo-Catalan conspiracy”. This was hardly surprising.

In the eyes of the Catholic, conservative and rural-agrarian traditions of the central Spanish meseta of Castile and Andalucia, the resourcefulness of the Catalans as merchants, traders, and their industriousness, literacy, sobriety and international connections across the Mediterranean in both North Africa and the Levant evoked the Jewish traits most held in ill repute by the church and stood in contrast to the haughty pride, devout religiosity, monastic institutions and exaggerated sense of honor and disdain for manual work that characterized the model of the Castilian gentleman (hidalgo).” (see Spanish Vignettes; An Offbeat Look Into Spain’s Culture, Society and History)

The late 15th century Kingdom of Aragon, prior to the so called “unification” of Spain with Castile, had capitalized on these commercial and maritime successes and embraced a territory extending from the Northeast of the peninsula to the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, Southern Italy and part of Greece.

Spain was “unified” in 1469 by the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon with Isabella of Castile-Leon. Nevertheless, the two halves of this kingdom maintained separate identities, languages, distinct, laws, weights and measures for another two hundred years. Until the early 1700s, the official title of the King was “Rey de las Españas” (in the plural to recognize the diversity of Castile, Aragon, Galicia, The Basque Country and Andalucia), just as the Czar titled himself as “Czar of all the Russias.”

As early as 1640-1652, Catalunya tried to follow Portugal’s successful revolt and reimpose its language, laws, customs, and traditions but without success. During the War of the Spanish succession (1699-1702) the Catalans supported the losing cause of the Hapsburg dynasty. By 1707, the authorities in Madrid imposed a through uniformity throughout the kingdom extending to laws, currency, weights and measures and language.

The Catalans made a transition to a modern economy and became the dynamo of Spain, outdistancing economic activity in the rest of the country. During that time, Barcelona grew much faster than any other city in Spain. Industry in the manufacture of paper, iron, wool, leather, textiles and processed fish, as well as in the export of wine and cotton led to a new sense of confidence and prosperity.

The 20th Century and its Conflicts

Since the end of the 18th century, disaffection grew, as the central power in Madrid wasted enormous resources in numerous unsuccessful, vain, and costly enterprises trying to retain control of its empire in Central and South America, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Morocco, and the Philippines, all held in little regard as remote and distracting by all Catalans. The wealth of Spain, in part, plundered from the expelled Jews and Moors and indigenous peoples of the “New World” was squandered.

Barcelona was the scene of a spontaneous uprising that began on Monday 26th July 1909 when the city was shut down by a massive general strike. The revolt started after the government had called up military reservists to fight in Morocco. Trams were overturned, communications cut and trains carrying troops were held up by women sitting on the rails. The city has retained this reputation as a hotbed of opposition to authority. No wonder the current government in Madrid feared the outcome of holding any referendum in Catalunya, the goal of which was independence, and would reignite old passions.

The Lasting Linguistic Divide

Catalan nationalists argue (correctly) that Catalan is much closer to Latin and has more words of Greek origin than Castilian which absorbed both Basque and Arabic elements. The most politically incorrect remark a foreigner can make about Catalan is that it is a “dialect” of “Spanish”. In fact, Portuguese, the language of an independent nation for more than eight hundred years is closer to Castilian-Spanish than Catalan.

By the eighth century, most of the peninsula was under the invaders. The languages of the western half of the peninsula in Galicia and Leon resembled Portuguese and had a certain Celtic as well as Germanic influence whereas those in Aragon, Catalunya, and the Balearic Islands were closer to Rome. Sounds common in Arabic, Basque and Castilian Spanish include the harsh guttural “j”, “ch” and ñ sounds are absent in Catalan. All over Spain, road signs have been overwritten with graffiti in the Catalan and Basque areas with the local language equivalents (see postscript below).

The international devised language, Esperanto, resembles Catalan more than any other national language and this similarity was used as a screen by Catalan nationalists during the early period of General Franco’s rule (circa 1940 until about 1970) when Catalan was suppressed, frowned upon and practically excluded from any public manifestation or cultural exhibition.

The language issue has long been the source of irritation for Catalans who have to remind the world that their language is spoken by more people, close to nine million, throughout Spain (as both a first and second language), than speak Danish (barely 6 million speakers) yet not accorded any recognition by the institutions of the European community or outside of Catalunya. Compare this with the official status of Erse with no more than 20,000 speakers.

Catalan is accorded the same status as Scottish Gaelic (50,000 speakers) as a “semi-official” language by the EEC. Over the last few decades, the local authority (Generalitat) of Catalunya has succeeded in making Catalan the language of instruction in all state primary and secondary schools much as the Quebecois have done with French in Quebec. Similarly, various regulations ostensibly guaranteeing bilingualism in Castilian Spanish and Catalan are often interpreted to favor the local language.

The Civil War and Since Then

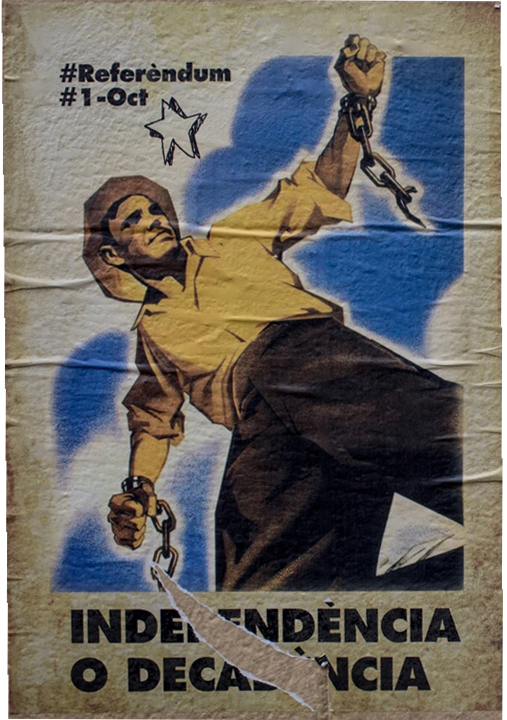

Catalunya also proved to be the most loyal region in Spain to the ideals of the short-lived Republic (1931-1939) and was the stronghold of resistance to the Fascist uprising commanded by General Franco. Barcelona, the seat of much political power in the hands of Catalan nationalists, socialists, Trotskyites, and Communists was the last major base to fall and the Franco regime crushed every attempt to maintain Catalunya’s sense of individuality, including any remnant cultural and linguistic separateness.

This even extended to sport as matches between the two greatest football (soccer) clubs FC Barcelona and Real Madrid were subject to intense political pressure during the 1950s and 60s to ensure a victory by the Madrid club.

In the last years of his life, General Franco (died 1975) began to make tentative reforms relaxing the tight control over Catalunya and the Catalan language, hoping it would pave the way for the regime to follow him. His successors believed they had succeeded and have been taken by surprise by the new round of aggressive assertions of Catalan identity and the renewed call for independence.

Catalunya thus has a much stronger claim to individuality and separateness from the rest of the country than the Scots have. They are however, like the Scots, aware that to demand secession would plunge the economy and society of the two regions into chaotic conditions provoking bloodshed among fellow citizens and even among families. This explains the high proportion of voters in the referendum who simply refused to take part or cast blank ballots. Their NATO allies are aghast as this potential conflict, the roots of which go back more than seven hundred years, and poses what might be called a threat to security from Muslim North Africa.

On Sunday, October 8, a massive rally in Barcelona with a crowd of more than half a million matchers organized by Societat Civil Catalana, the region’s main pro-unity organization demonstrated the rejection of both resident Catalans and many others in the region to separate from Spain. The march featuring the slogan “Let’s recover our common sense”, called for dialogue with the rest of Spain.

The Catalan president, Carles Puigdemont, is under growing pressure to stop short of declaring independence amidst threats from major companies and banks to abandon the region. He has given contradictory answers to Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy about how he interprets the result of the referendum. The Spanish constitution already recognizes that the Catalans constitute a “nation within a nation.” What more can be done for them in the U.N. and in the European Union?

As in Quebec, where two unsuccessful referenda for independence were narrowly defeated, the great majority of the population outside the disputed region simply wishes to restore harmony but believes that no further compromises should be made. Spanish friends and allies must convince the Catalans that their heritage and history can be secured but only without confrontation and in solidarity with other Spaniards against a real threat to them all from militant Islam.

The issue remains cloudy at this juncture.

Postscript

Standard Spanish,

CATALUÑA, ¿UNA NACIÓN?

Cataluña está unida al resto de España desde hace más de 500 años, desde que los Reyes Católicos (Isabel y Fernando) unen los reinos de Castilla y Aragón.

Sin embargo, en el tipo de monarquía que había en España, cada uno de los antiguos reinos y principados que la integraba gozaba de una cierta independencia: leyes e instituciones propias, pago de impuestos, derechos y privilegios propios de cada zona . . . A este conjunto de leyes propias, derechos y privilegios se los conoce como fueros.

Cataluña nunca fue un reino independiente, formaba parte del reino de Aragón, pero era un principado que tenía una cierta independencia y unos fueros propios.

Carlos II, el último rey de la dinastía de los Austrias, muere sin heredero. El resultado es una guerra, la guerra de Sucesión, en la que se enfrentan dos aspirantes a la Corona de España: Felipe V, de la dinastía de los Borbones (Francia), y el archiduque Carlos, de la dinastía de los Austrias.

Text in Catalan

CATALUNYA, UNA NACIÓ?

Catalunya està unida a la resta d’Espanya des de fa més de 500 anys, des que els Reis Catòlics (Isabel i Ferran) uneixen els regnes de Castella i Aragó.

No obstant això, en el tipus de monarquia que hi havia a Espanya, cada un dels antics regnes i principats que la integrava gaudia de una certa independència: lleis i institucions pròpies, pagament d’impostos, drets i privilegis propis de cada zona . . . A aquest conjunt de lleis pròpies, drets i privilegis se’ls coneix com fueros.

Catalunya mai va ser un regne independent, formava part del regne d’Aragó, però era un principat que tenia una certa independència i uns furs propis.

Carles II, l’últim rei de la dinastia dels Àustries, mor sense heredero. El resultat és una guerra, la guerra de Successió, en la qual es enfrentan 2 aspirantes a la Corona d’Espanya: Felip V, de la dinastia dels Borbó (França), i l’arxiduc Carles, de la dinastia dels Àustria.

English Version

Catalunya has been joined with the rest of Spain for more than 500 years since the Catholic Monarchs (Isabel and Fernando) united the kingdoms of Castile and Aragón.

Nevertheless, in the type of monarchy that existed in Spain, each one of the ancient kingdoms and principalities that comprised the country enjoyed a certain degree of independence: each with its own laws and institutions, taxes, rights and privileges. This complex of maintaining its own laws, rights and privileges is known as “fueros.”

Catalunya was never an independent kingdom; it was rather a principality which formed part of the Kingdom of Aragon, but rather, a principality that had a certain independence and some its own fueros.

Carlos II, the last king of the Dynasty of Asturias died without an heir. The result of this was a war, The War of Spanish Succession in which two claimants to the Spanish throne clashed: Felipe V, of the Bourbon Dynasty (France) and the Archduke Carlos, of the Asturias Dynasty.

____________________________

Norman Berdichevsky is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting and informative articles, please click here.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Norman Berdichevsky, click here.

Click here to see all Norman Berdichevsky’s blog posts on The Iconoclast.