by Richard Kostelanetz (December 2016)

One myth propagated in post-1970 America held that artists, especially avant-garde artists, no longer needed to go abroad to establish their careers, thanks to increasing largess from our universities and arts councils; but this smug assumption was false, simply because American institutions scarcely supported truly advanced artists, some of whom earned greater recognition abroad.

After 1970 or so, the most inspiring place to go in Europe was not Paris, which attracted previous generations, but Berlin, initially West Berlin, which was from 1961 to 1989 a cultural oases geographically inside/within another country, the DDR (East Germany), whose government had constructed an impregnable wall around the Western parts of the historic city. Greater West Germany proper was hours away by car.

One magnet bringing American artists and writers there was an extraordinary program developed in the 1960s to invite two dozen artists annually from the around to be in residence for a year. Founded by an American Cold-War operative named Shepard Stone, initially with American government money channeled through the Ford Foundation, it was passed onto the German DAAD, or Academic Exchange Service, and thus called its Berliner Kunstlerprogramm. The ulterior motive was continuing, perhaps artificially, the pre-WWII tradition of Berlin as an artistic capital for the western world. (To be impressed by the number, range, and excellence of those invited, consider: http://www.berliner-kuenstlerprogramm.de/en/gaeste.php.)

Among the American 1976 stipendiats, as they are called, was Dorothy Iannone (b. 1933, Boston), a sometime literature graduate student who became an eccentric painter in the late 1950s, exhibiting mostly in a small New York gallery that she ran with her American husband. (That’s the gallery world’s “self-publishing.”) Once divorced and residing in West Berlin, Iannone slowly became a major American expatriate artist/writer (as did Emmett Williams, another avant-garde artist/writer who came on the same program in 1980, whose apartment became temporarily mine in the following spring before I passed it onto the composer Arvo Part in the fall of 1981).

Honored with one-person exhibitions in Switzerland, Germany, and France, Iannone became an American–European to a degree that few American-born ever attain. Perhaps because Iannone has stayed in Berlin. Only in 2009 did a New York museum honor her work, albeit in a single space apart from a larger show of another artist. Around the same time her work was included in a Whitney Museum biennial. These constitute foreplay, so to speak. May I speculate that some American institution is now preparing a major retrospective; if not in fact, then one should be.

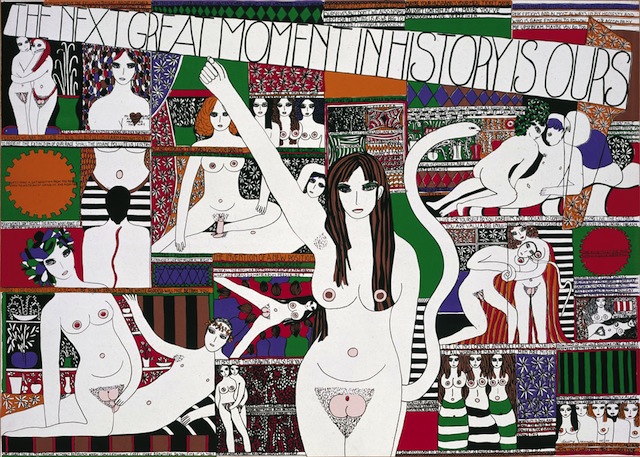

Given Iannone’s literary background, it’s not surprising that her paintings and drawings typically contain handwritten words, sometimes elegantly phrased, usually in English, which nearly every sophisticated European understands today (much as a century ago French was universal). Iannone’s favorite subject has been her female body, including uniquely stylized genitals, often remembering her own ecstatic erotic experience, especially with the major European artist Dieter Rot (German-Swiss-Icelandic, 1930-1998). Even now, nobody else’s visual art looks remotely like hers. In her courage for displaying herself, Iannone resembles the American-American artist Hannah Wilke (1940-1993); but whereas Wilke’s theme is exhibitionistic narcissism, Iannone’s is, as I said, about her relations with men.

Decades ago in New York, she must have been an art-world knock out, as her early husband was a millionaire and among her previous lovers were a prominent American painter and an even more prominent American writer both of whose last names begin with the letter M. (Need I explain that an art-world knock out would be competitively beautiful only among artists, not among actresses, say, just as Kenneth Koch could be funny only where poetry was expected but not on the same stage as Henny Youngman.)

As an aside, may I note surprise at some Wikipedia scribe’s citing the New York Times: “In 1961 she was arrested by U.S. Customs at the Idlewild [now JFK] Airport in Queens, New York for trying to import The Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, which was banned at the time. Iannone sued the U.S. Customs with assistance from the New York Civil Liberties Union, which caused her book to be returned and the ban on Miller to be lifted.” Surprised may I be, as that previous summer I luckily buried in my luggage several banned Miller books for a A.B. honors thesis at Brown University the following spring. (More amusingly, I recall, the Customs’ snitch found in my luggage Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi, which I pointed out to him had already been published in America by New Directions and was thus acceptable in the USA. Once the gumshoe consulted his colleagues and that obstacle was resolved, Customs reluctantly closed my luggage.) Incidentally, whereas sex for Miller is polymorphous pleasure, for Iannone coupling with a man seems to epitomize heightened feminine experience.

Once in Europe, Iannone became connected to Rot, a spectacularly fecund and obsessive visual artist who incidentally also wrote highly original texts (one of which is reprinted in my anthology Breakthrough Fictioneers [1973]). Much of her early European art variously illustrates her relationship with him. One theme is this work is an American woman’s discovery of Europe in the 1970s, much as Henry Miller’s classics portray an American’s discovery of Paris in the 1930’s,

(Curiously, Dorothy Iannone shares a rather unusual Italian surname with the American conservative writer Carol I., some fifteen years younger. Knowing them both thirty years ago, I then asked each if she was aware of the other. Neither was, perhaps suffering from the prejudice common at the time, even among Italian-Americans, that no one with a surname ending in a vowel could do significant cultural work. My further hunch is that, if Carol had known about Dorothy when Carol first began to publish forty-five years ago, Carol might have taken a pseudonym. Nonetheless, may I respect the mystery implicit in common names even if others don’t.)

Many of Dorothy I.’s images have been reproduced in illustrated books whose pages must likewise be read as well as viewed. From Siglio Press, recently in Los Angeles (soon to move to New York), as well as two European publishers (to no surprise), have recently come handsome selections of her art. Printed in Thailand and thus reasonably priced in dollars, You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends has elegantly printed 8” x 10”, with color signatures between a wealth of black and white reproductions rich in visual, verbal, and verbal/visual detail, all reflecting the editorial love of its publisher/editor Lisa Pearson. The masterpiece, in my judgment, is “The Darling Duck” (p. 277), which portrays a man and a woman copulating while upside down in a visual field containing handwritten verbal text that is thoughtfully transcribed to printed type in the previous pages.

You Who Read Me wants—indeed begs–to be owned by anyone ever viewing it. What’s missing is documentation of her as, according to my Berlin-based sometime filmmaking partner Martin Koerber, “a pioneer of multimedia art, perhaps. Some of her work involves video or sound, often with as much or more sexual content than her other stuff. I saw her one-woman show in 2014 at Berlinische Galerie.” The catalog accompanying this exhibiton, Dorothy Iannone: This Sweetness Outside of Time (2015), contains a wealth of pictures mostly in color from her entire career, albeit with texts only in German.

The principal recurring fault of You Who Read Me is lines of tiny type five inches wide that are difficult read. (Consider double columns, especially on such wides pages?) Nonetheless, one charm of these Dorothy Iannone books is enabling art-word-lovers to “collect” her visual/verbal images without spending thousands of dollars. Go for them.

Incidentally, when asked by people who care about such sub-categories about the “most important Italian-American woman writer ever,” my choice would be Dorothy Iannone—no one else.

___________________________________________

Richard Kostelanetz recently completed a book of previously uncollected critiques, Deeper, Further, and Beyond. Individual entries on his work in several fields appear in various editions of Readers Guide to Twentieth-Century Writers, Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of Literature, Contemporary Poets, Contemporary Novelists, Postmodern Fiction, Webster’s Dictionary of American Writers, The HarperCollins Reader’s Encyclopedia of American Literature, Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Directory of American Scholars, Who’s Who in America, Who’s Who in the World, Who’s Who in American Art, NNDB.com, Wikipedia.com, and Britannica.com, among other distinguished directories. Otherwise, he survives in New York, where he was born, unemployed and thus overworked.

Richard Kostelanetz recently completed a book of previously uncollected critiques, Deeper, Further, and Beyond. Individual entries on his work in several fields appear in various editions of Readers Guide to Twentieth-Century Writers, Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of Literature, Contemporary Poets, Contemporary Novelists, Postmodern Fiction, Webster’s Dictionary of American Writers, The HarperCollins Reader’s Encyclopedia of American Literature, Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Directory of American Scholars, Who’s Who in America, Who’s Who in the World, Who’s Who in American Art, NNDB.com, Wikipedia.com, and Britannica.com, among other distinguished directories. Otherwise, he survives in New York, where he was born, unemployed and thus overworked.

To comment on this article or to share on social media, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish thought provoking articles such as this one, please click here.

If you have enjoyed this article and want to read more by Richard Kostelanetz, please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link