by David Wiener (May 2021)

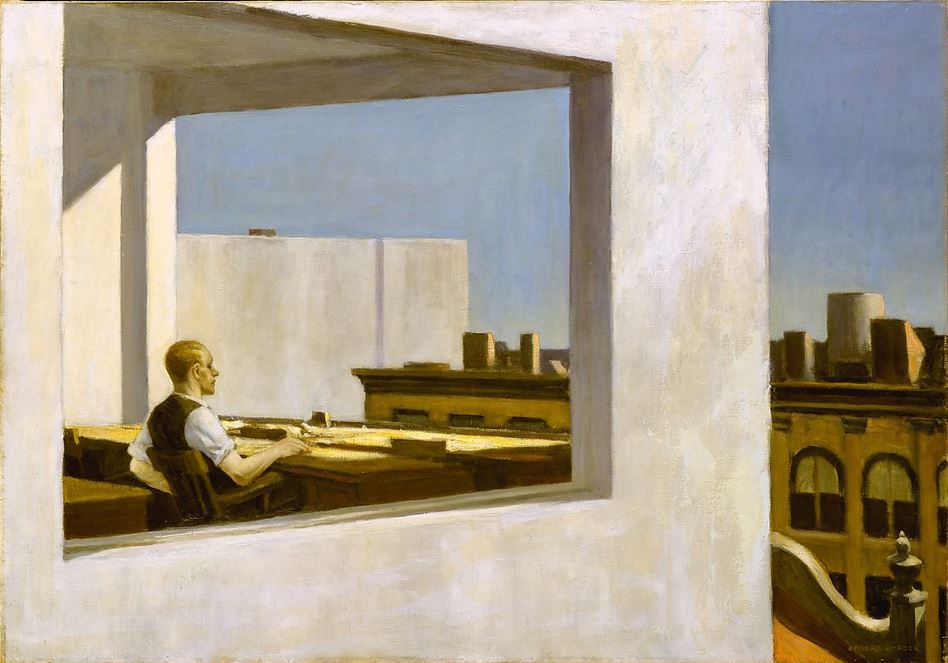

Office in a Small City, Edward Hopper, 1953

“Hey, Mr. Trask. Come on in. I’m Todd Delroy.”

“The editor,” Trask said with a little grin and they shook hands.

“I suppose so.”

“I appreciate you seeing me, I really do,” Trask said.

He dropped into a chair and Delroy sat behind his desk. That was unusual for him. A student intern passed by the open door and jerked back, looking a little surprised.

“Doing OK today, Mr. Delroy?”

“Fine, yeah.”

The kid walked on, with a little shrug. He’d never seen the editor sitting down before, not that he could remember. Delroy usually spent his day in constant motion; drifting around his desk, pacing when he was on the phone, marching across the hall to chat with the layout people, trotting down to the machines for a snack.

Delroy smiled at Trask; he smiled back. Delroy knew very well why he was sitting down. The desk was the only substantial barrier he could put between himself and Trask. At their worst, writers were usually shifty and whiny, but this guy actually made him nervous. Trask had called, practically begging to come in and talk about a story of his that had been rejected (“The Frog Who Knew Too Much;” the title needed changing).

Trask had sounded like a student arguing a grade and over the phone his voice sounded a little strangled, like his throat was tightening up from anxiety–or maybe anger. But now that he met him in the flesh, he seemed cordial enough. But he looked weird and just to be in his presence was really quite disturbing.

The only way he could put it was that there was “something about his eyes.” After 26 years of shaping and polishing other people’s words, that was the best he could do to describe what it was about this man that bothered him so much. And made him suddenly so wary. A hackneyed pulp-fiction phrase–“There was something about his eyes.” But there was something wrong with them. Him. History of violence? Boozer? Half a bubble off plumb—more than half?

Yes, there was an office procedure for dealing with disgruntled ex-employees, crazed boyfriends, and the like. It was in the Employee Manual. He hadn’t read it. He’d never need it. Editing sci-fi, horror, and mystery mags occasionally brought him into contact with letters from crazies, but never before with an actual crazy, up close and personal.

Why did you agree to see him? Pity. Just about the only time he dealt face to face with writers was at the annual award party for Best Stories of The Year. At the sports bar around the corner from the Denny’s near the office. And the writers at that affair were happy, silly, and harmless. They grinned as they had their photos taken cradling a Lucite-and-chrome ray gun engraved with their name and the title of their story. Kind of made you want to cry. Last year one of them had been so shy, she had to be coaxed out of a phone booth just to accept her award.

This guy, he realized the instant he ushered him into his office, was not like that. And so, the desk between them.

Delroy decided that the best approach would be to keep the conversation bland and generic; ask him about himself, about other stuff he’s working on, be upbeat, encouraging, noncommittal. Don’t give him the impression he’s being brushed off. And Trask responded well. He smiled and told him about a novella he was working on (“It’s set in a women’s prison colony on Phobos, right? Kind of racy.”).

Delroy swallowed hard and kept nodding as he struggled to keep the disarming smile on his face from freezing solid and racked his brain trying to figure out a way TO GET THIS GUY OUT OF MY OFFICE.

“Well, like I said,” Delroy noted in soothing tones, “you’re not a bad writer, not at all, and that’s the truth . . . but this particular story just—doesn’t—suit our needs at this particular—“

Trask would not be mollified.

“Look,” he said, “I appreciate all that but I was hoping that you’d just tell me straight out what’s wrong with this story?”

Delroy took a quick look around at the other office cubicles, just to see who was close by. Nobody. Wonderful. Down the hall, there was the clacking of someone’s electrical typewriter. That was it.

OK, fruitcake, it’s just you and me.

“Well,” Delroy made a little cough and said, “I love—we love parallel universe stories. Everybody loves a good parallel Earth story. But, it’s just—a parallel universe story must be credible. You know? Believable, plausible.”

Trask was silent, taking in what Delroy was saying. OK, maybe the constructive criticism route was the best way to go. Maybe. Hope so. What in God’s name was it with this guy’s eyes?

“I mean, the other universe can be a great setting for a funny sci-fi or a deadly serious sci-fi. But, whatever direction you take it, the other Earth has to be, or seem, every bit as real as our own. You know?”

Trask was shaking his head back and forth like he was thinking “No” and muttered, “Irony instead of iron maiden.” Huh? Just pretend you didn’t hear, Delroy told himself. And keep making with the helpful suggestions.

“Curriculum instead of crushed testicles,” Trask added.

Oh, Jesus.

The eyes never lie. Delroy softened his voice even more and said, “Your—your parallel Earth? The detail is admirable, Mr. Trask, I mean you’ve managed to paint a word-picture that’s pretty complete in a very short space. But—I’m just not buying it. Your parallel Earth doesn’t hold up. Not for me, anyways.”

“But why?” Trask said, almost pleading. “Why isn’t it believable?”

In for a penny, Trask thought. OK, buddy, you want the truth, here it is.

“It’s just—” Delroy said. “Your other Earth—I mean, just look what went on with your parallel Earth. TWO world wars in 30 years?! And constant mayhem and slaughter in between? Even a million casualties would strain credulity. You’ve got, what, 100 million-plus men, women, children killed off? Dead in battle, displaced, starved, beaten, tortured, terrorized, worked to death, burned alive, buried alive, experimented on, gassed, butchered by their own countries! It’s too much! I don’t buy it—nobody would buy it.”

“Oh.” Trask said.

“It just wouldn’t work, not in its current form is what I’m getting at. Let’s say your parallel Earth did exist—it would be endless anarchy! Nobody, but nobody, would ever believe anything a government or government official told them, ever. There could BE no kind of government, no form of administration—they’d all be too despised, they’d kill every official and bureaucrat on sight!”

“Or,” Trask offered, “they’d look to them for salvation and follow them blindly and believe what they’re told—as long as they’re fed some kind of noble-sounding rhetoric along with it. Of course, the place would go bankrupt and the rulers would have to rush around doing all kinds of crazy things to hide that fact and—and—well, they’d also be much more technologically advanced than us, more, uh, scientific because nothing moves science ahead faster than actual long-term warfare on a vast scale . . . ”

The editor just nodded.

“War,” Trask continued, “well, as a means of social engineering—you know, it’s really much messier and far more expensive than doing the same thing in more subtle ways. Right?”

Jesus. If he avoided eye contact, maybe Trask would get the idea that the meeting was over. Delroy glanced at the morning paper waiting for him on his desk: “Legislature Passes New Guidelines for Humane Vivisection of Juvenile Slaves,” the headline read. He frowned and thought, “I bet someone stole the sports section again…”

He looked back at Trask and saw that he now had a sort of glazed-over, distant look in his very strange eyes.

“Sometimes” —Trask paused as a look of pain washed over his face— “sometimes, that other place seems awfully real to me, you know? I mean, real real, like I’m peeking behind a veil and getting these glimpses of that other Earth. And I’m seeing everything that’s happened and going on over there.”

They find me, Delroy thought to himself, how do they find me?

“Team-building instead of torture,” Trask whispered, as if he were revealing the secrets of the universe. “Remold it nearer to the heart’s desire,” he added with his eyes squeezed shut. “Celebrity spokesmen instead of strappado, 24-hour headlines instead of head-busting, raising awareness instead of raising welts, ostracism instead of Oswiecim.”

Oh, God, Delroy thought, what did I get myself into letting this lunatic into my office? Was Trask on medication? Or had he stopped taking it?

And, just as quickly as they glazed over, Trask’s eyes shifted again in some indescribable way and returned to the bizarre look they had when he first walked into the office.

Delroy seized the opportunity and stood.

“Please send us other stories, Mr. Trask,” he said. “I mean that, I do. With the right plot, I know you’d do a wonderful job. I want to see more of your stuff. OK?”

Trask nodded quickly, stood, and held out his hand.

“Well, I certainly appreciate you taking the time to talk with me today,” he said.

Uh-oh. Now what? He grabs my hand like he’s gonna shake it and twists my arm around my back and then out come the boxcutters?

But not shaking his hand could also set him off.

So Delroy grabbed Trask’s hand. And Trask shook it. And let it go; he even smiled a friendly smile.

Jesus, Delroy thought. Jesus, just relax, man. He’s almost gone…

Trask turned and walked through the office door.

And then he stopped.

Goddamn it, Delroy thought, I knew it, I just KNEW it! The bastard IS nuts—I KNEW IT! God DAMN it, I just had a feeling—

“Hey,” Trask said, his smile getting bigger, “wouldn’t it be a hoot if somewhere on that other Earth, you know, the one that had the two world wars and 100 million slaughtered, right this very minute over there, there’s a guy trying to sell a short story just like mine about an alternate Earth just like ours where there had never been two world wars— but all kinds of really hideous and unspeakable stuff had been done anyways, but always really gradual, strictly slow and sneaky, easing people into accepting it all as being just normal life and their rulers impose their will through stuff like belief restructuring without ever having to bring out the rubber hose or go to the trouble of a shooting war to get the people in line, see? And folks just go along with the program and don’t make a stink so the honchos can pretty much do whatever they like to as many people as they want and nobody thinks it’s weird or even very upsetting? You know?”

With that, Trask was out the door and down the hall.

“Well,” Delroy muttered as he let out a long, shaky sigh, “I just hope that poor, dumb bastard has better luck selling his story than you had selling yours . . . ”

__________________________________

David Wiener has written cover, feature, and interview articles for various performing arts magazines including American Cinematographer, Producers Guild Journal, Cahiers du Cinema, and The Journal of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain. His plays have been produced in London, India, Canada, Australia, Mexico, and the U.S. and have been published three times in the Smith & Kraus “Best Plays” one-act anthology series. In 2007, he completed a Literary Internship with La Jolla Playhouse and went on to work as that theatre’s Dramaturgy Associate during the 07-08 season.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link