by Jillian Becker (October 2022)

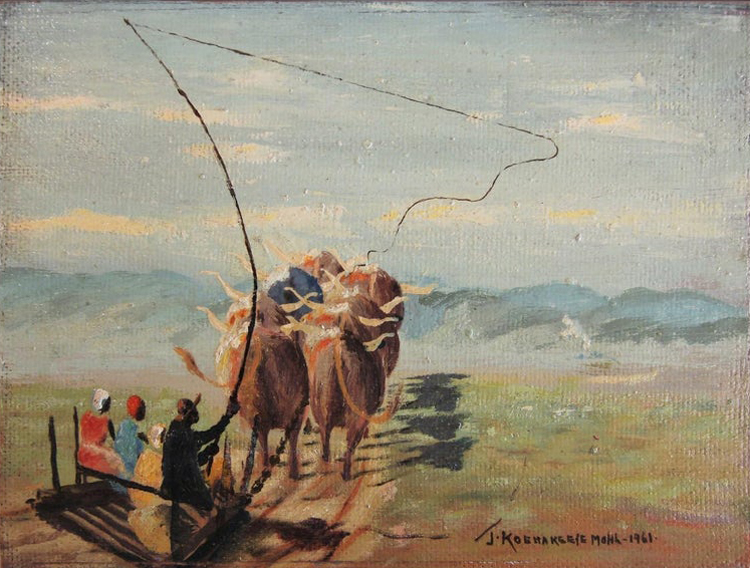

Mid Summer Journey on Sledge, John Koenakeefe Mohl, 1961

I am a child of the British Empire, born a subject of His Britannic Majesty King George V in the Union of South Africa in 1932. At that time you could travel from the southernmost tip of Africa all the way up the continent to the Mediterranean Sea without leaving British-ruled territory. I still esteem the lost Empire, believing—as Rudyard Kipling did—that it did much good for the peoples it conquered and guarded. And I am grateful to it for giving asylum and freedom to my ancestors who fled persecution in Europe decades before the Holocaust. But that does not mean that I find no fault with it, or don’t laugh at its follies, or lack sympathy with the men and women among the native peoples who suffered injustice at the hands of its governors—not only the ruthless and dishonest officials but also the conscientious and upright.

In the story that follows—known as “the Serowe incident” —the hero is a native of Africa, a born leader of men, and the British colonial administrators are the mugginses.

Serowe is a large “urban village” in central Botswana. It was founded in 1902 as the capital of the Bamangwato people in what was then the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, one of the poorest countries in the world. For decades it was the largest village in southern Africa, consisting of thousands of skillfully-built thatched mud-huts and a few hundred European-style houses, one of which was the Chief’s House.

On Sunday the 13th August, 1933, a brawl in the village blew up into an historic event in the annals of the British Empire, a grave incident involving race relations that ended in the trial and banishment of the Bamangwato Chief, Tshekedi Khama. A man of high intelligence and graceful manners, competent, well educated, loyal to the British Crown and respectful of the law, he was the Regent Chief, chosen by his nation in 1925 when he was only twenty, to lead them until his then four-year-old nephew Seretse, the dynastic heir, would reach his majority.

On that fateful Sunday, a youth mellifluously named Ramananeng reported to the Chief that he had been beaten and severely hurt by two young white men, Phinehas McIntosh and Henry McNamee, after he’d called out a rebuke to them about black women having “indecent intercourse with white boys.”[1]

The accused were a pair of delinquents, born in Serowe, both with a record of unruly, drunken, violent behaviour. Tshekedi had frequently pleaded with the officials of the Administration, in particular the Resident Magistrate, Captain J. W. Potts, to deal effectively with them since he himself did not have the authority over white residents to arrest, try, and punish them. He could not expel them from the Bamangwato Reserve, as he would like to do. Potts had been less than helpful, only responding tetchily that Tshekedi himself could and should order the Bamangwato women whom the two young men debauched, including those whom McIntosh lived with as a series of wives in a mud-hut of his own, to return to their mothers. Tshekedi was more than willing to do this. He was strongly against miscegenation and had unsuccessfully tried to persuade the imperial government to make a law against it like the one in the Union of South Africa, but he pointed out that there was a difficulty in the case because of the half-caste children born to the women. What was to be done with them, he wanted to know. To whom did they belong? The Administration had no answer, and took no decisive action to stop Phinehas McIntosh and his chum Henry McNamee from debauching, robbing, assaulting and drunkenly brawling.

The beating of Ramananeng was a last straw for Tshekedi. He summoned McIntosh, the older of the two hooligans and at twenty-one legally an adult, to appear at the kgotla, his open-air assembly and periodic court, for an “enquiry” into the incident.[2]

McIntosh obeyed. On the appointed day he appeared before the Chief and his headmen. They considered the event to be of small importance; “just a trifling matter where harlots were concerned,” one of the headmen was later to say.[3]

Yet what happened there that day had consequences which shone a spotlight on the obscure country of Bechuanaland, sent British grandees travelling thousands of miles, launched a deployment of Marines, raised turbulence in far-off Whitehall, blazed throughout the Empire, generated innumerable newspaper headlines and preoccupied columnists for weeks, and eventually inspired investigations by historians and the writing of substantial books—although nobody was ever quite sure what precisely did happen.

It was confidently asserted in official records that Tshekedi ordered the culprit to be flogged. Others insist that such an order was not given.[4] But even if the order was given, was it carried out? Someone, it was generally agreed, probably Tshekedi himself, spoke of a flogging, and as soon as McIntosh heard the word, he started toward the Chief to ask him to be let off the punishment. That, he later explained, was what he understood was the customary thing for a condemned offender to do. He claimed that he walked towards Tshekedi, but witnesses said he dashed, he ran, he charged. Whatever the speed of his movement was, it provoked the headmen and Tribal Police to assume that his intention was to assault the Chief. They leapt to intercept him, and he was flung to the ground. One of the policemen (an old enemy seizing the opportunity for revenge, McIntosh claimed) struck out at him with a sjambok, and some of the lashes landed on his back. (Later, tears in his clothes showed that the whip had reached his body, and a doctor testified to finding two weals on his back such as would be made by a whip.) But before he could be subjected to a concentrated flogging, Tshekedi shouted that he was to be left alone. So McIntosh was subjected to no judicial punishment for his battering of Ramananeng.

Tshekedi wrote a carefully worded letter to every European household in Serowe to explain what he had done. In it he referred to Phinehas McIntosh familiarly by his shortened name “Phean.” A messenger bore the letter from house to house. It read in part:

“You may hear rumours that I had occasion to give corporal punishment to young Phean McIntosh on my Kgotla this morning … However, before such corporal punishment could be given, Phean made a dash at me and the people present caught hold of him to stop him, and I do not know whether he was badly handled or not—I stopped the people from doing him harm, and after this nothing was done to Phean in the way of punishment. It has always been my principle to treat my white residents with respect … Punishment this morning was given with no malice, but with determined effort of giving a check to this endless trouble and unbecoming influence.”[5]

He sent another, more detailed letter of explanation to Captain Potts, the British Resident Magistrate in Serowe. Potts was shocked by what he read and inaccurately informed Colonel Charles Rey, the British Resident Commissioner of the Bechuanaland Protectorate (who was not actually resident in the Protectorate but carried out his official duties from Mafeking, a town in South Africa near the border of Bechuanaland and the Administrative capital of the Protectorate) that a white man had been flogged on the order of the native chief Tshekedi Khama.

Relations between Colonel Rey and Tshekedi were far from easy. They clashed over matters of policy, most seriously over the question of mining. Rey was for it, Tshekedi against it.

Colonel Rey, wanting to achieve a development of lasting consequence for the country while it was under his administration, argued that mining would greatly increase the prosperity of the nation by providing employment, while also profiting investors in Britain and the wider industrialized world.

Tshekedi was against it. He foresaw that the opening of mines would bring an influx of white settlers. He feared that Bechuanaland would come to be a white-majority country like South Africa. If that happened, he anticipated, it would not be long before the self-governing British dominion of South Africa would annex the territory (as it made no secret of wanting to do), and if his country were to be incorporated in the Union, his people would be subjugated, oppressed and humiliated as all the black peoples were in the four provinces of the dominion.

Rey was frustrated and infuriated by Tshekedi’s obstinacy. So when he heard by telegram from Captain Potts that the Chief had ordered the flogging of a white man, he was instantly filled with triumphant glee. “I’ve got the little bugger now,” he cried out to his private secretary.[6]

Everything that followed in connection with the flogging of Phinehas McIntosh resulted from that intense emotional reaction of Resident Commissioner Colonel Rey to the news of it.

Rey seized what he saw as a perfect opportunity to rid himself of opposition to his ambitious plans by having Tshekedi Khama deposed. He hastened to cable his immediate superior, the Acting High Commissioner of the British Protectorates of Bechuanaland, Swaziland and Basutoland, Admiral Edward Ratcliffe Garth Evans, stationed in South Africa, informing him that the native chief had had a white man flogged. In view of the extreme seriousness of the situation, he said, he must have a meeting as soon as possible to discuss what was to be done.

The meeting took place in the South African administrative capital Pretoria. There Rey briefed Evans fully on the appalling scandal. They were joined by the Administrative Secretary from the High Commissioner’s Office in the legislative capital Cape Town, and the High Commissioner’s Legal Adviser. The Administrative Secretary cabled the British Secretary of State and the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs. Rey impressed upon all the powers in the imperial chain of command above him that it was necessary to take “immediate and drastic action” to prevent “render[ing] insecure the position of Europeans in the Territory,” causing the Government “to be regarded with contempt,” and making it “impossible to carry on the administration of the Territory.” He deplored Tshekedi’s “effrontery and insolence,” his “complete and barefaced defiance of all authority” (which was the opposite of the truth, an outrageous lie).[7]

Rey intended the implications of the warnings to be fearful; to raise visions of the natives rising in rebellion and Europeans being subjected to unnameable atrocities and slaughter. In short, disaster on an unprecedented scale would befall a sizeable chunk of the British Empire in Africa if Tshekedi Khama were not subjected to exemplary punishment and removed from office with the utmost urgency.

As rapine and massacre loomed, Acting High Commissioner Admiral Edward Ratcliffe Garth Russell Evans, an officer accustomed to taking responsibility in crises and issuing decisive commands, instantly grasped the need for forceful action to stop this chief, Tshekedi Khama, whose shadow was rapidly lengthening over British Africa and potentially over the entire Empire. The action he unhesitatingly took was to send in the Marines. Before consulting or even notifying London, he dispatched, on the 10th. September—just four days after the scene at the kogotla— “a detachment of maximum strength.”[8] with three howitzer guns, by train from Simonstown on the southern point of the continent (a port which the British leased from the Union of South Africa) to Palapye Road in Bechuanaland, the nearest rail station to Serowe.

The arrival of the Marines with their howitzer guns in the vast, quiet, largely empty desert land north of the Limpopo River was to become the stuff of legend. Accounts of what happened next—what official reports say happened and the story that the people of the country, black and white, love to tell—diverge.

According to the more dramatic popular version as told to me in 1968 by a young Serowe resident in the company of three other young Serowe residents (two black men, two white) who all indicated by occasional nods of assent that they believed it to be true, this—in my own words—is what ensued:

As the train crossed the border north of Mafeking and began to chug through the land of red dust and thorn trees, unseasonable rain fell. By the time the train pulled up at Palapye Road station the country was a sea of red mud.

The sailors in their neat white uniforms alighted. They were drawn up in ranks on the road to Serowe in the rain, their rifles on their backs, and, led by their commanding officers, started on the 30 mile march.

Marching was made difficult by the ankle-deep mud; and the big guns on wheels, drawn by their crews in the rear, soon sank into it.

The commanding officer realized that they had no choice but to ask Tshekedi Khama for teams of oxen to drag their artillery out of the mud so they could be drawn to his capital and used to threaten him and his people.

Leaving the guns and their crews behind them, the sailors completed their advance with difficulty and were allowed to break rank and seek shelter where they could in the center of the village, while the officer went to find the Chief.

Tshekedi was waiting for him, seated comfortably on his covered verandah. He received the lieutenant with his usual courtesy, greeting him kindly though he did not rise, and listening attentively while the bedraggled young man standing before him in his soaked, mud-spattered uniform, dripping on to the floorboards of the verandah, did his best to comport himself with British imperial dignity as he made his request. He would have liked to issue it as a command but was as much aware as Tshekedi that he was in fact begging a favor.

When he was done explaining that the big guns were stuck in the mud outside Palapye Road station and oxen were needed to drag them out and pull them to Serowe, and asking if a sufficient number of the beasts could please be borrowed or hired for the purpose, Tshekedi expressed sympathy and assured the officer that he fully understood and regretted his predicament. He promised to do everything in his power to get teams of oxen dispatched as soon as possible.

As it turned out, for reasons that were never made clear, no oxen could be taken from the farms that day, or the next day …

That was the end of the story—except for the answer to a question of mine. Yes, the guns were eventually dug out of the mud and dragged to Serowe. But that was an unimportant detail to the teller and his friends for whom the delight of the tale lay in the embarrassment and humiliation of the Imperial Power.

To this day the story that the guns got stuck and Tshekedi had to send oxen to pull them out and draw them to Serowe is still told. The rain and the consequent mud—vivid ingredients of the young man’s tale—are usually omitted. Yes, says the revised version, the guns sank but in the soft sand of the road. Yes, Tshekedi sent the oxen—just as soon as he was told they were needed.

But there is no more than a scintilla of truth even in that version.

What actually happened was this.

Tshekedi, summoned to Palapye, spent the night before the arrival of the Marines in the town’s small and only hotel. He knew he was to face some sort of trial in connection with McIntosh but had not been told what if anything he was to be charged with. Very early in the morning of 12th. September, his lawyer (and friend), Douglas Buchanan, arrived, in response to his request, by train from Cape Town. Tshekedi told him about the trouble he’d had with McIntosh and McNamee, in particular their unacceptable relations with black women; that McIntosh had committed numerous offences including violent assault; that the white authorities had not taken any measures to deter or punish him, and that he himself, Tshekedi, had finally brought McIntosh to a kgotla enquiry and had strongly rebuked him, but had not punished him.

Tshekedi’s trial—or “administrative enquiry” as the officials insisted on calling it—was held on Wednesday the 13th September on open ground in Palapye. The area was surrounded by loaded guns in the hands of the Marines. Admiral Evans arrived by plane. Tshekedi was handed a letter, dated three days earlier, telling him that he was suspended from his chieftainship and was to be held in custody in the police camp at Palapye. Buchanan was forbidden to speak for his client on the grounds that the enquiry was “administrative” and not “judicial.” Tshekedi himself cross-examined witnesses, chiefly Phinehas McIntosh and Henry McNamee—who admitted everything he accused them of—and argued for himself so cogently, eloquently, and effectively that the prosecution was left without a case to pursue and the enquiry was closed. The judgment, Tshekedi was told, would be announced by Admiral Evans next day in Serowe.

Early on that day the Marines, who had been accommodated in tents, were set on the road to Serowe. Behind them three mechanized howitzer guns were driven. Two got through the sand with some difficulty, the third sank deep and its crew took time and effort to raise it. No oxen were asked for or sent.

A dais was erected on a large open space in the center of the village. The Union Jack was hoisted over it. Newspaper correspondents and photographers got as close to the dais as they could. A vast crowd of Tshekedi’s people were directed to keep beyond a white line drawn behind the place where Tshekedi was to stand. The British officers gathered near the dais, including a high diplomat titled the Deputy Commissioner for the United Kingdom wearing a splendid official hat decorated with a wealth of richly coloured cock feathers. As a three-gun salute was fired, Admiral Evans alone mounted the dais. Standing up there, he announced the verdict and sentence. Tshekedi was guilty of ordering the flogging of the white man Phinehas McIntosh. Consequently he was suspended from his chieftainship, banished to Francistown in the north of the territory, and forbidden contact with his people.

The short speech was met with total silence. Evans descended from the dais, got into the car awaiting him, and was driven off.

Then the silence was broken. “The whole white population,” including the parents of Phinehas McIntosh, “came forward in a body and each in turn, men, women, and children, filed past Tshekedi, shook his hand and told him how sorry they were for what has happened and that they hoped he would soon return as Chief.”[9]

As a policeman put a hand on Tshekedi’s shoulder to take him away, the crowd of his tribesmen began to raise their voices in anger. Tshekedi faced them, spoke to them, calmed them down with an assurance that “Everything will be all right,”, and walked to the car that was to carry him away from them.[10]

Tshekedi’s period of banishment in Francistown did not last long. It was over in thirteen days. Buchanan sought and obtained permission for him to move to Cape Town and Tshekedi arrived there on the 29th September. He at once cabled King George V to thank him for his kindness and assure him of his continuing loyalty.

Admiral Evans invited him to tea on his flagship and informed him that he was to be reinstated as Chief in Serowe the following week.

Phinehas McIntosh and Henry McNamee were sent south to Lobatsi, a “white town” on the border with South Africa, and put to work in a road gang, but not imprisoned. They behaved well, and in 1937 Tshekedi allowed McIntosh, by then married to a white wife, to return for the rest of his life to Serowe where he became a respected citizen.

Also in 1937, Resident Commissioner Rey retired, went to live in Cape Town, and became Sir Charles Fernand Rey.

And what happened to Henry McNamee, who had partnered Phinehas McIntosh in drunken rioting and the beating of Ramananeng, from which the infamous Serowe Incident had ensued? It is hard to find anything further about him. But I do know when and where his life ended.

Before I tell that piece of the story I must first relate what happened to Bechuanaland.

In 1966 the Bechuanaland Protectorate became the independent Republic of Botswana. Its first president was Seretse Khama, Chief of the Bamangwato, who had married a white woman, Ruth Williams, in 1948, in defiance of his uncle Tshekedi’s opposition to the match.

In 1967 the South African mining company, de Beers—which had a world-wide diamond monopoly—found black diamonds in Botswana. Where black diamonds are found “real” diamonds will also be found, and they soon were.

In August 1968 I travelled by Land Rover, with two companions, to and about Botswana. On the first day we passed through Lobatsi and came to the capital, Gaberones.[11] Its main street was macadamized, lined with shops and electric lights. A Barclays Bank flew—unaccountably—a United Nations flag. British and American flags fluttered here and there in the warm wind. The blue-and-white national flag flew over the House of Assembly.

In the dining room of the new, grand, air-conditioned President Hotel we saw a large party of diners at one long table. They were government ministers and representatives of de Beers, the head waiter told me. The dinner was a celebration of an agreement reached between the government and the company over the mining of white diamonds. As a result of that find, Botswana has since become the fourth richest country per capita in Africa, beating even South Africa, the fifth richest.*

A few days later we came to Serowe. The road from Palapye was sand all the way. For miles on either side of it, nothing but reddish-beige earth and thorn trees. And then, surprisingly, on either side, amid thorn trees, suddenly there were hundreds of thatched huts the colour of the earth in the gloaming.

The white proprietor of the comfortable single-storey hotel—Digger, he was affectionately nicknamed—grew tulips in his garden. They were in full bloom, I saw on the first morning, and was surprised, thinking, “Tulips in such a warm climate and in such sandy soil?”

It was the 9th August, 1968. Digger asked us if we would like to go to a funeral. “A lot of people will be going to this one,” he said. We accepted his offer to drive us to the popular event. On the way he told us that the man who was to be buried, Henry McNamee, had been involved in an incident years ago, way back in the 1930s, when he was eighteen, and he and another young man named Phinehas McIntosh had beaten up “a black kid” and Tshekedi Khama had ordered McIntosh to be flogged. He laughed as he told us how the British government officials had been so angry about it that they had sent up “sailors with big guns” by train from Cape Town to suppress what they thought was an uprising of the blacks against British rule. Then he told us that the rain had fallen and churned up mud on the road from Palapye and the big guns had stuck in the mud and the the commanding officer had had to go and beg Tshekedi for oxen to pull them out. “It made news all over the world,” he said. But the Chief had soon been allowed to come back. And eventually McIntosh had also come back to live in Serowe “with his white wife” and caused no more trouble. “But the other one, McNamee—he never reformed. He continued to drink excessively, brawl, act violently. Thing is, he raped a lame Bamangwato girl. He was hated for that. For a long time he dared not show his face in Serowe. The rumour was that he was living with a black woman somewhere along the railroad. We saw him sometimes, and recently he came back and we heard he was ill and then that he had died. And today he’ll be buried.”

There was quite a large crowd at the graveside, whites and tribesmen. We all watched quietly as the pastor read the burial service and the coffin was lowered into the grave. We lingered on, reading the names and dates on the headstones when everyone else had gone. It was then that we saw a lone black woman, tall and erect though not young, standing on the side of McNamee’s open grave. She bent, picked up a handful of earth and held it out over the lowered coffin. As it poured down on to the wooden lid she called out some words in Tswana.

“What did she say?” I asked Digger.

“She said ‘Go well, my friend’.”

We watched her turn and walk away, limping.

[1] The Flogging of Phinehas McIntosh by Michael Crowder, Yale University Press, 1988, p.1

[2] There was much precedent for disputes in which white residents were concerned coming before the kgotla for settlement.

[3] Crowder p. 42

[4] Tshekedi Khama by Mary Benson, Faber and Faber, London, 1960, p. 110

[5] Crowder p. 44

[6] Crowder p. 45

[7] Crowder p. 49

[8] Crowder p. 52. I found no record of how many were in the “detachment of maximum strength”. It probably consisted of about 40 men.

[9] Benson p. 98

[10] Benson p. 98

[11] The name was changed later to Gaberone.

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal (Europe), Encounter, The Times (UK), The Telegraph Magazine, and Standpoint. She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren. Her website is www.theatheistconservative.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

7 Responses

A wonderfully insightful look into the workings of the bureaucracy of the British Empire in its decline. Charmingly told.

Your first para contains much wisdom in all its lines- I marvel that today there can be no measured criticism of things like the British Empire when compared to far worse sins, or that by defending it in any way I will often be presumed to have ruled out considering even the most trifling sins. Similarly, your point that the benign and benevolent of intent can cause as much harm as the deliberately villainous seems deeply obvious to me, but seems equally incomprehensible to millions today. I practically consider it a given that clueless but genuine do-gooders will inflict harm, at least at the margins. Or that unimaginative bureaucrats with intents whether good or bad will also inflict harm, even without intending it.

With all that in mind, this is a brilliant illustration. If it had happened in another empire perhaps Horace or Gogol would have recounted it.

Is “muggins” a slang term? To me, of much later vintage, it evokes a combination of “buggins” from Jackie Fisher’s “Buggins’ turn” sarcasm about admiralty appointments processes, and “muggles” from Harry Potter. Which is actually close to what you seem to intend, come to think.

mug·gins

/ˈməɡinz/

Learn to pronounce

nounINFORMAL•BRITISH

a foolish and gullible person (often used humorously to refer to oneself).

“muggins has volunteered to do the catering”

The British empire was probably at its best when it occasionally used law and threat to keep the ne-er do wells of the motherland from getting out and causing embarrassment in the colonies. The officials were sometimes fairly well acquainted with the lowlife of Britain and its infelicities. Plus it avoids the trouble of having to defend them against native justice which so often causes a diplomatic problem not to say a public ruction among the homeland guuetr press.

The phenomenon is not unknown in more recent times, as that young American ostensibly caned for something in Singapore can address, or any number of westerners arrested and perhaps abused for alcohol or sexual offenses in the Gulf.

That ended much more happily, if not entirely without mystery, than I expected. I was fully anticipating a much, much darker tale.

During our three years (1968-71) in Botswana parts of this story came to us when wife Linda and I were teachers at both Serowe and Lobatse Teacher Training Colleges. We arrived in Serowe in August, 1968 after a long trip from NE Ohio; College Principal Jackson picked us up at Palapye hotel the morning after we had arrived at 2:00 a.m. by train. A beautiful people to live with and great memories. We could never forget those three years and the people.

Thanks for this full account,

Wayne J Yoder