by Robert Lewis (September 2020)

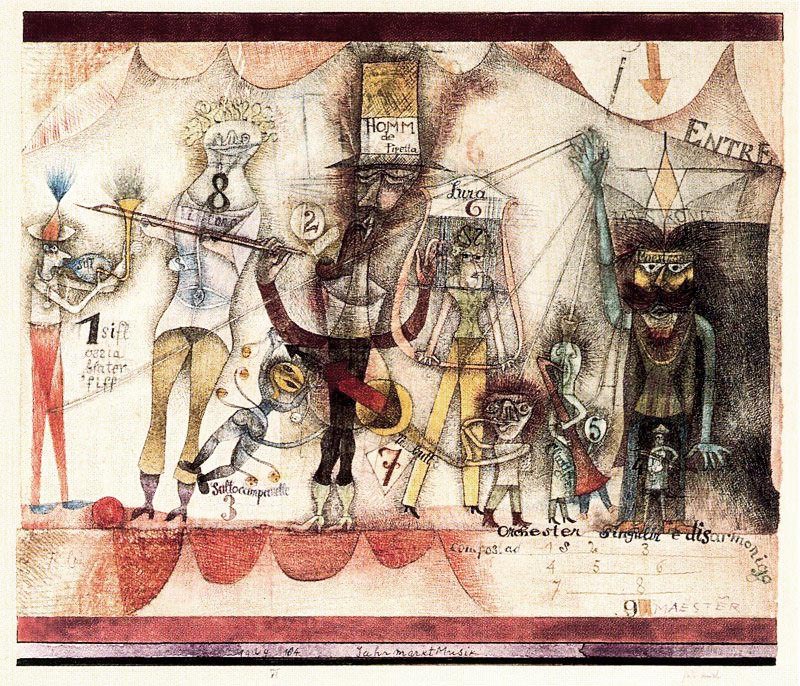

Music at the Fair, Paul Klee, 1924-26

During the past 75 years, the verb “to hit”—from the Norse hitta (to come upon, to find and, later in England, to strike—has undergone radical transformation in order to qualify the pleasurable effects of music on the brain.

Prior to music’s appropriation of the word, its associations were mostly negative: to physically hit someone was to do him harm; one can be hit hard by an economic downturn, a region by bad weather, the loss of a close friend or loved one. In sports the verb “to hit’ is used to illustrate and quantify violent impact: a driver or baseball bat striking a ball, a Mike Tyson right hand dropping an opponent.

Separating the impact of the word from its common usage, heroin users were among the first to change the valence of ‘hit’ from negative to positive. A ‘hit’ or to ‘hit up’ identifies smack’s (slang for heroin) happy effects on both mind and body. “I’ll take a hit of that” now figuratively refers to anything that produces agreeable effects—from drugs and alcohol to a splash of water on a dry tongue.

In consideration of music’s immediate impact on the brain, and the often cozy relationship between drugs and creativity, it became fashionable in the 1930s to designate a popular piece of music as a ‘hit.’ In 1936, Billboard magazine introduced its first Hit Parade listings, a ranking of the most popular recordings on a given date. Once entered into the vernacular, the positive recasting of the word, especially in the context of culture and entertainment, quickly caught on: journalists began characterizing a successful Broadway show, art exhibition or television series as a ‘hit.’ An actor could be singled out as the ‘hit’ of the show, or he/she the ‘hit’ of the party.

Prior to the Internet, a number one hit was strictly determined by sales and airplay. A chart buster typically appealed to a narrowly defined segment of the population united by language and dispersed over a large geographical area. In 1957 Elvis Presley’s “I’m All Shook Up” topped the charts and sold more than two million copies. But today, in the digital era of high-speed dissemination and downloading of music, song popularity is now measured in sales and Internet (youtube) views and must appeal to a global audience—m meaning it has to be sung in the lingua franca of the world: English. Justin Bieber’s “Baby” has been viewed over a billion times. Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep” has registered more than 700 hundred million plays while Rihanna’s “Diamonds in the Sky” over 600 million—and still counting.

In consideration of the above numbers and paying the rent, there isn’t a songwriter alive who doesn’t dream of writing a top-selling record, which on the surface seems easy since most hits consist of no more than a few basic chords. But there is probably nothing more difficult in all of music—putting together a sequence of notes that beguiles the brain in such a way that millions around the world want to hear those notes again and again, perhaps twenty times a day; not unlike a crack-user wants to light up all day long. In both examples, the ‘hit’ (the notes or the drug) pleasures the brain and sets in motion a dopamine cycle that is its own reward and terminus.

Worldwide, there are thousands of aspiring songwriters writing pop songs, implicitly competing with each other, all trying to come up with a sequence of notes that will appeal to and insinuate themselves, and to a certain extent take over and empower minds everywhere in the world. Since no more than three or four hit records are produced every year, when they hit, it is with tsunami-like force that unites millions of listeners who might otherwise have nothing in common, for whom the ‘hit’ represents a transcendent frontierless universal culture that constantly renews itself with each succeeding hit, much like the form of the fountain remains the same despite the constant replacement of water that is being propelled. That a burqa-clad teen in a Berber tent is listening to the same music as a Beijing waitress is a civilizational conjunction whose positive and negative implications are only beginning to be understood.

Compared to their future selves, teenagers are developmentally more receptive to the immediate hit music provides because transitioning from child to adult (becoming self-conscious) is necessarily a lengthy and painful process that is marked by a tidal wave of anxieties over body image, popularity, and relationships. Besides bonding around a preferred music, most teens quasi-obsessively seek out the direct ‘hit’ embedded in their favourite run of notes in order to feel good about themselves, to heal their hurting, to vent their anger and frustration, and especially to forget about everything but the moment in song. “There’s a melody for every malady” writes the composer Stew in his rock musical Passing Strange.

It’s enough to make you believe in the pseudoscience of alchemy when one considers both the degree and extent to which a minimal line of music is able to transform and empower especially young listeners, an observable fact that was dramatically brought to my attention during the viewing of the 2014 French film Bande de Filles (Girlhood) by Céline Sciamma, which follows the hard scrabble life of four girls living in the outskirts (the projects) of Paris. As a matter of course, the girls decide to resort to petty crime to scratch up enough coin for a hotel room where for a night only—free from authority and the pressures of growing up fast—they can live their dreams. In the film’s most remarkable scene that takes your breath away, Rihanna’s “Diamonds in the Sky” starts up and the girls bounce off the bed and burst into dance, and for those brief two or three minutes their fondest hopes for connection and happiness are experienced as real, as they and the entire viewing audience are magically transformed into the beautiful sparkle and shine that are diamonds in the sky. The simple notes combined with the lyric hit the brain so forcefully that the song doesn’t even require a bridge: it’s the same notes repeating again and again, simultaneously connecting millions of like minds around the world, many for whom English is not a mother tongue.

Because the ebb and flow of the world is constantly changing as an effect of new technology, the new music will necessarily reflect the latest changes while its mission remains the same: empower the mind and dull the pain. A hit from the 1950s or 60s will not resonate today because its sound, texture, and rhythm speak a different language which doesn’t speak to the present. For a song to become a hit, its very specific gravity has to be able to attract young people from around the world in order to lift them out of the deep and make them feel good about themselves for as long as the song lasts. Of necessity, the hit will be both a reaction to the world as it turns and an escape to a far better place.

Since the passing of time and change are the two great constants in life, it comes as no surprise to observe that as teenagers mature and become settled in their ways, they listen less frequently to music, that the medicinal the notes dispensed is no longer required.

* * * * *

Just as eternity feeds on time, the hit record feeds on youth, meaning as long as there are young people up in mid-air, the mega-hit, as a multi-purpose delivery system, will continue to be a constant in the world because it’s the one friend that will never let you down, or, as sung by Bob Marley in “Trenchtown Rock,” “one good thing about music when it hits you feel no pain, hit me with music.”

Like a river whose flow is continuous but shape never changes, number one hits will come and go, but their essence will remain the same as the upsurge of those privileged and yes, brilliantly conceived sequences of notes that allow listeners to experience, however temporarily, however implausibly, intimations of what it feels like to be fully realized and integrated into the world.

Best said by the late Mentor Williams:

Give me the beat boys and free my soul

I wanna get lost in your rock and roll

And drift away.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Robert Lewis was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He has been publislhed in The Spectator. He is also a guitarist who composes in the Alt-Classical style. You can listen here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link