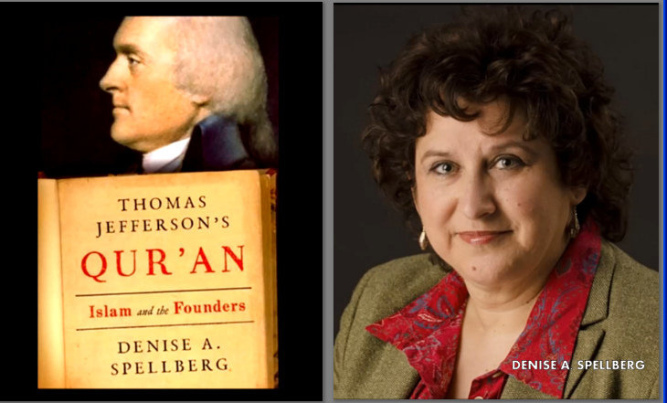

by Hugh Fitzgerald

Whenever there is the swearing-in of a Muslim on Jefferson’s Qur’an, or whenever there is an Iftar Dinner held at the White House, Denise Spellberg uses the occasion to trot out the same article she’s been republishing for the last five years, as here or here, the one entitled “Jefferson’s Quran” or “Jefferson’s Iftar Dinner,” or “Why Jefferson’s Vision Of American Islam Matters Today.” She is dutifully interviewed on television, where she claims that the fact that Jefferson once bought a Qur’an shows that “Islam has been part of American history for a long time.” No one thinks to ask her: If Jefferson had bought a copy of the Bhagavad Gita, would that show that Hinduism had always been “part of America’s story”?

Here’s the latest iteration by Spellberg of the same article, with only a handful of words changed to connect it to what’s currently in the news at the time of writing — from Keith Ellison’s swearing-in to President Trump’s failure to hold an Iftar Dinner in 2017, to Rashida Tlaib’s recent swearing-in, like Keith Ellison’s before her, that was announced to be on Jefferson’s Qur’an, but turned out to on her own copy.

Muslims arrived in North America as early as the 17th century, eventually composing 15 to 30 percent of the enslaved West African population of British America. (Muslims from the Middle East did not begin to immigrate here as free citizens until the late 19th century.) Even key American Founding Fathers demonstrated a marked interest in the faith and its practitioners, most notably Thomas Jefferson.

This claim that 15-30 percent of slaves in America were Muslims, a claim now so often repeated that it has become unquestioned “common knowledge,” defies belief. How is it that the slave owners themselves failed to notice all these Muslims among their slaves? And why did the other, non-Muslim slaves, not report to their masters on the existence of these Muslims? Why did this subject come up only in the last few decades, coinciding with the attempts to claim that “Muslims have always been part of America’s story”? This does not mean there were no Muslim slaves; we do have records of about 10-20 slaves who appear to have been Muslims. But to leap from this number — one one-thousandth of 1% of the total number of slaves — to the claim that “15-30%”of the slaves were Muslim” — is absurd.

“Even key American Founding Fathers demonstrated a marked interest in the faith and its practitioners,” she claims. No, they did not. Neither Washington, nor John Adams, nor Madison, nor Alexander Hamilton, nor John Jay, nor Benjamin Franklin. And what little they did write about Islam was always negative. As for John Adams, his owning a Qur’an did not signify an endorsement of Islam. On July 16, 1814, in a letter to Jefferson, John Adams described the Muslim prophet Muhammad as one of those (he listed others as well) who could rightly be considered a “military fanatic,” one who “denies that laws were made for him; he arrogates everything to himself by force of arms.” Adams is nowhere on record as praising any aspect of Islam, nor even “advocating” its toleration. The only president who ever exhibited a “marked interest” in Islam, the only one known to have actually read the Qur’an, was John Quincy Adams, the son of a Founding Father and the most learned of our presidents. J. Q. Adams did study Islam, and wrote about it at great and horrified length. He grasped its essence perfectly:

The precept of the koran is, perpetual war against all who deny, that Mahomet is the prophet of God. The vanquished may purchase their lives, by the payment of tribute; the victorious may be appeased by a false and delusive promise of peace; and the faithful follower of the prophet, may submit to the imperious necessities of defeat: but the command to propagate the Moslem creed by the sword is always obligatory, when it can be made effective. The commands of the prophet may be performed alike, by fraud, or by force.

Spellberg describes Jefferson as “advocating for the rights of the practitioners of the [Muslim] faith.” This implies special pleading on his part for Islam. What Jefferson actually did was “advocate” for the principle of religious freedom in general, and famously quoted a line from John Locke’s 1698 A Letter Concerning Religious Toleration: “neither Pagan nor Mahamedan [Muslim] nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the Commonwealth because of his religion.” What Spellberg does not mention is that Locke himself, from whose writings Jefferson derived his own views on religious toleration, later exempted from such toleration those believers who exhibited certain unacceptable features. He expressly excluded, according to his own criteria, four kinds of believers. First, those whose religious opinions are contrary to “those moral rules which are necessary to the preservation of civil society”; second, believers in a religion that “teaches expressly and openly, that men are not obliged to keep their promise”; third, those that will not own and teach the duty of tolerating all men in matters of mere religion…and that they only ask leave to be tolerated by the magistrate so long, until they find themselves strong enough to [seize the government]”; fourth, “all those who see themselves as having allegiance to another civil authority.” Specifically, Locke gives the example of the Muslim who lives among Christians and would have difficulty submitting to the government of a “Christian nation” when he comes from a Muslim country where the civil magistrate was also the religious authority. Locke notes that such a person would have serious difficulty serving as a soldier in his adopted nation (cf. the 2009 Fort Hood shooting spree by Nidal Hassan,who shouted “Allahu akbar” as he opened fire, killing 13 and wounding 32).

Islam meets not just one, but all four of Locke’s criteria for being exempt from “toleration.” Did Jefferson see Locke’s list of criteria for exempting a faith from toleration? We don’t know. But his attitude toward Islam, whatever he thought about tolerating it, remained consistently negative. Contrary to the impression Spellberg hopes to give, by sleight of word, Jefferson never found anything good to say about Islam.

Jefferson’s first encounter with real Muslims came when he, along with John Adams, met with the Tripolitanian envoy Sidi Haji Abdrahaman in London in 1786. They asked the envoy “concerning the ground of the pretensions to make war upon nations who had done them no injury” to deserve being attacked, and the ambassador replied, as Jefferson reported:

It was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave; and that every mussulman who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise.

And later, Jefferson reported to Secretary of State John Jay and to Congress at greater length:

The ambassador answered us that [the right] was founded on the Laws of the Prophet, that it was written in their Koran, that all nations who should not have answered their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as prisoners, and that every Mussulman who should be slain in battle was sure to go to Paradise.

These reports did not come from someone who thought well of Islam. The more dealings Jefferson had with the representatives of the Barbary states, the more he grasped the aggressive nature of Islam, as first set out to him by that Tripolitanian envoy: the centrality of Jihad (even if Jefferson did not use that word), holy war waged as by right against non-Muslims, the inculcation of permanent hostility toward non-Muslims, and the heavenly reward for Muslims slain in battle against the Infidels.

Jefferson did not, despite Spellberg’s claim, demonstrate a “marked interest” in the faith. As a 22-year-old law student in Williamsburg, Virginia, he bought a Qur’an, just as he bought many books on many subjects, ultimately leaving a library of 6,487 books. There is no evidence that Jefferson ever read his Qur’an. There are no notes he left about its contents, no marginalia written by Jefferson, no subsequent reference anywhere to his having read any part of the Qur’an. Spellberg surely knows that. But she is determined to endow that Qur’an purchase with significance. She claims that “the purchase is symbolic of a longer historical connection between American and Islamic worlds, and a more inclusive view of the nation’s early, robust view of religious pluralism.”

What “historical connection” was there between the “American and Islamic worlds” that she so casually alludes to, hoping we will not think too deeply about the claim? The main “connection” in our earliest days as a nation was that of warfare waged against us by the Muslim privateers — the “Barbary Pirates,” as they were known — who attacked Christian shipping in the Mediterranean, including the ships of the young Republic. It was during his negotiations in London in 1786 over these attacks with the envoy from Tripoli, and in subsequent dealings with the Barbary Pirates, that Jefferson received his greatest lesson about Islam.

Although Jefferson did not leave any notes on his immediate reaction to the Qur’an, he did criticize Islam as “stifling free enquiry” in his early political debates in Virginia, a charge he also leveled against Catholicism. He thought both religions fused religion and the state at a time he wished to separate them in his commonwealth.

Note that Spellberg assumes, and wants us to assume, that Jefferson read the Qur’an, but “did not leave any notes on his immediate reaction.” That implies he left some notes later on. But he did not ever leave any notes on the Qur’an. She should have written, to be accurate, that “although there is no evidence that Jefferson read the Qur’an he bought as a student, he did criticize Islam as ‘stifling free enquiry.’”

Despite his criticism of Islam, Jefferson supported the rights of its adherents. Evidence exists that Jefferson had been thinking privately about Muslim inclusion in his new country since 1776. A few months after penning the Declaration of Independence, he returned to Virginia to draft legislation about religion for his native state, writing in his private notes a paraphrase of the English philosopher John Locke’s 1689 “Letter on Toleration”: “[he] says neither Pagan nor Mahometan [Muslim] nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion.”

This is not “advocacy for” Islam, but advocacy for toleration of all faiths, including Islam. These are different things.

By the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, adopted in 1786 (before his fateful encounter with the Tripolitanian envoy in London), Jefferson intended that religious liberty and political equality would not be exclusively Christian. For Jefferson asserted in his autobiography that his original legislative intent in the Virginia Statute had been “to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan [Muslim], the Hindoo, and Infidel of every denomination.” The final version of the Virginia Statute, as adopted, left out this explicit statement; not everyone was prepared to cast the net of toleration that wide.

By including Muslims as future citizens in the 18th century, Jefferson expanded his “universal” legislative scope to include every one of every faith.

Ideas about the nation’s religiously plural character were tested also in Jefferson’s presidential foreign policy with the Islamic powers of North Africa. President Jefferson welcomed the first Muslim ambassador, who hailed from Tunis, to the White House in 1805. Because it was Ramadan, the president moved the state dinner from 3:30 p.m. to be “precisely at sunset,” a recognition of the Tunisian ambassador’s religious beliefs, if not quite America’s first official celebration of Ramadan.

There is a deliberate attempt here to make us believe — it is more explicit in some of Spellberg’s other writings — that Jefferson was somehow recognizing Ramadan, and turning a state dinner into the “first Iftar dinner.” Jefferson was neither recognizing Ramadan nor putting on an Iftar dinner. A little history will help: Sidi Soliman Mellimelli came to Washington as the envoy of the Bey of Tunis. The Americans had blockaded the port of Tunis in order to force the Bey to halt his attacks on American shipping. Mellimelli was sent to make an agreement that would end the blockade. Invited by Jefferson to a dinner at the White House set for 3:30 (dinners were earlier in those pre-Edison days of our existence), he requested that it be held after sundown, in accordance with his Muslim practice, and Jefferson, a courteous man, obliged him. There is no hint that the dinner had changed in any way; no one then called it, or thought of it, as an “Iftar dinner.” Mellimelli himself never described it as an “Iftar dinner.” There is no record of it being anything other than the exact same dinner, the same menu, with wine (no removal of alcohol, as would have been necessary had it been a real Iftar dinner), the only change being that of the three-hour delay until sunset.

Muslims once again provide a litmus test for the civil rights of all U.S. believers. Today, Muslims are fellow citizens and members of Congress, and their legal rights represent an American founding ideal still besieged by fear mongering, precedents [sic] at odds with the best of our ideals of universal religious freedom.

Denise Spellberg alludes to islamocritics who she claims are still “besieging American ideals” with “fear mongering.” It is not, pace Spellberg, “fear mongering” to point out the 109 Qur’anic verses that command Muslims to engage in violent Jihad (such as 2:191-194, 4:89, 8:12, 8: 60, 9:5, 9:29, 47:4), that Muslims are told in those verses to “fight them [the Unbelievers] wherever they are,” to “smite at their necks,” and to “strike terror” in their hearts. It is not “fear mongering” to note that Muslims are taught that they are the “best of peoples” and Unbelievers “the most vile of created beings.” It is not “fear mongering,” but perfectly legitimate, to ask what we are to make of such comments by Muhammad in the Hadith as “war is deceit” and, still more significant, his claim that “I have been made victorious through terror.” And if any “American ideals” are being besieged, it is not that of freedom of religion but rather, that of freedom of speech, at the hands of those who wish, like Spellberg, to impugn and drown out those well-informed islamocritics.

Had Jefferson been aware of Locke’s four criteria for “exemptions” from religious toleration, I suspect he would have been in agreement. But even had he continued to believe that Islam was entitled to toleration, that never meant he approved of the faith. He was horrified by the explanation offered by the Tripolitanian envoy in 1786 for the attacks on Christian shipping; he understood that Islam discouraged free inquiry; he was determined to use force against the Barbary Pirates, which he did as soon as he became President in 1801, for he knew from both his experience, and his study of history, that Muslims would respond, and submit, only to such force. If Islam was, as Spellberg disingenuously insists, early on “part of America’s story,” it was, as Jefferson saw for himself, not a very good part.

First published in Jihad Watch here and here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link