by Michael Curtis

By bizarre coincidence two events relevant to the same issue of racism and discrimination happened in Britain on the same day, March 31, 2021. One was the protest and mass walk out by hundreds of pupils at the upscale Pimlico Academy school in Westminster, London. The other was the publication of the 258 page Report of the British Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. They represent different and conflicting perceptions of the existence of racism in the country.

First, it should be said that though the Commission was established in response to the BLM movement and the increasing concern in Britain with race issues, there is no parallel between the magnitude of those issues in Britain and the U.S. Slavery was abolished earlier in UK than in U.S. and was not an issue that troubled national consciousness to the same degree as in the U.S. British police do not carry firearms, and there are fewer cases of police brutality though there are some caveats. Blacks are eight times more likely to be stopped and searched than whites; and prosecution and sentencing for blacks is three times higher than for whites. Blacks are 3% of the population but account for 12% of the prison population.

Though one can generalize that life is better for non-whites in UK than in U.S., undoubtedly disparities exist that are meaningful. The standard of living and the health of blacks is less good than that of whites. Unemployment rates are significantly higher for ethnic minorities who earn less on average than whites. Only 6% of black school leavers attend university, compared with 12% of mixed Asian school leavers and 11% of white leavers.

The Report is a nuanced document. The Commission warned that overt and outright racism persists and declared that more must be done to challenge racist and discriminatory actions. It did not believe that the UK was yet a post-racial country which has completed the long journey to equality of opportunity. It acknowledged that impediments and disparities for minorities do exist, but holds that few of them are directly related to racism. Britain is not a country where the system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities. The well-meaning idealism of many young people who claim that “institutional racism” exists is not born out by the evidence. Too often racism is used as a total explanation for the disparities for people from minority groups. However, evidence shows that other factors, geography, family influence, socio-economic background, culture, religion, have more significant impact on life chances than the existence of racism. Two indications of this are the increasing diversity in professions such as medicine and law, and the decline in the race pay gap.

Not surprisingly, the Report was received with predictable controversy and critical backlash. Advocates see it as suggesting a new positive direction to consider the issue of racism, while critics see it as whitewashing British attitudes towards minority groups and of sweeping history under the carpet. In a sense it is a false controversy. It is unfair to deprecate the Report as if it were the government’s attempt to portray the nation as the beacon of good race relations.

The purpose of the Report was to change the tone of the discourse, presently dominated by agitation, about the root causes of racial disparities and their persistence.

The Commission is critical of the argument of the existence of “institutional racism.” A narrative that argues that nothing has changed for the better, and that the dominant feature of our society is institutional racism and white privilege will not achieve anything but alienating people. Similarly, the Commission rejects the assertion that “systemic racism” is important for explanation of disparities, say in health and crime issues.

The Commission asserts that education is the single most emphatic success story of British ethnic minorities experience, showing that the majority of such pupils often outperformed their white peers. Critics insist that structural, institutional, and direct racism works in and through the educational system. This critical view ignores the evidence that some ethnic groups do better in education, and in the labor market than others. It also ignores the impact of the geographical factor. Disadvantaged ethnic minority groups are usually concentrated in areas where housing and education facilities are poor, and jobs are not available.

The Commission suggests that there be more focus on factors other than race, such as cultural heritage, religion, parental influence, when considering the educational, health and economic outcomes experienced by minority groups. It also calls for the government to deal with the issues of inequalities. The need for this had been suggested by previous government statements, such as the audit in 2017 which showed inequalities between ethnicities in different areas and in the treatment by the police and in the courts, and the Windrush scandal of 2018 which showed that people were wrongly detained, denied their legal rights and more than 80 were deported. Many of those affected were born British subjects of Caribbean origin, members of the “Windrush generation,” named after the Empress Windrush, the ship that brought hundreds of West Indian immigrants to the UK in 1948.

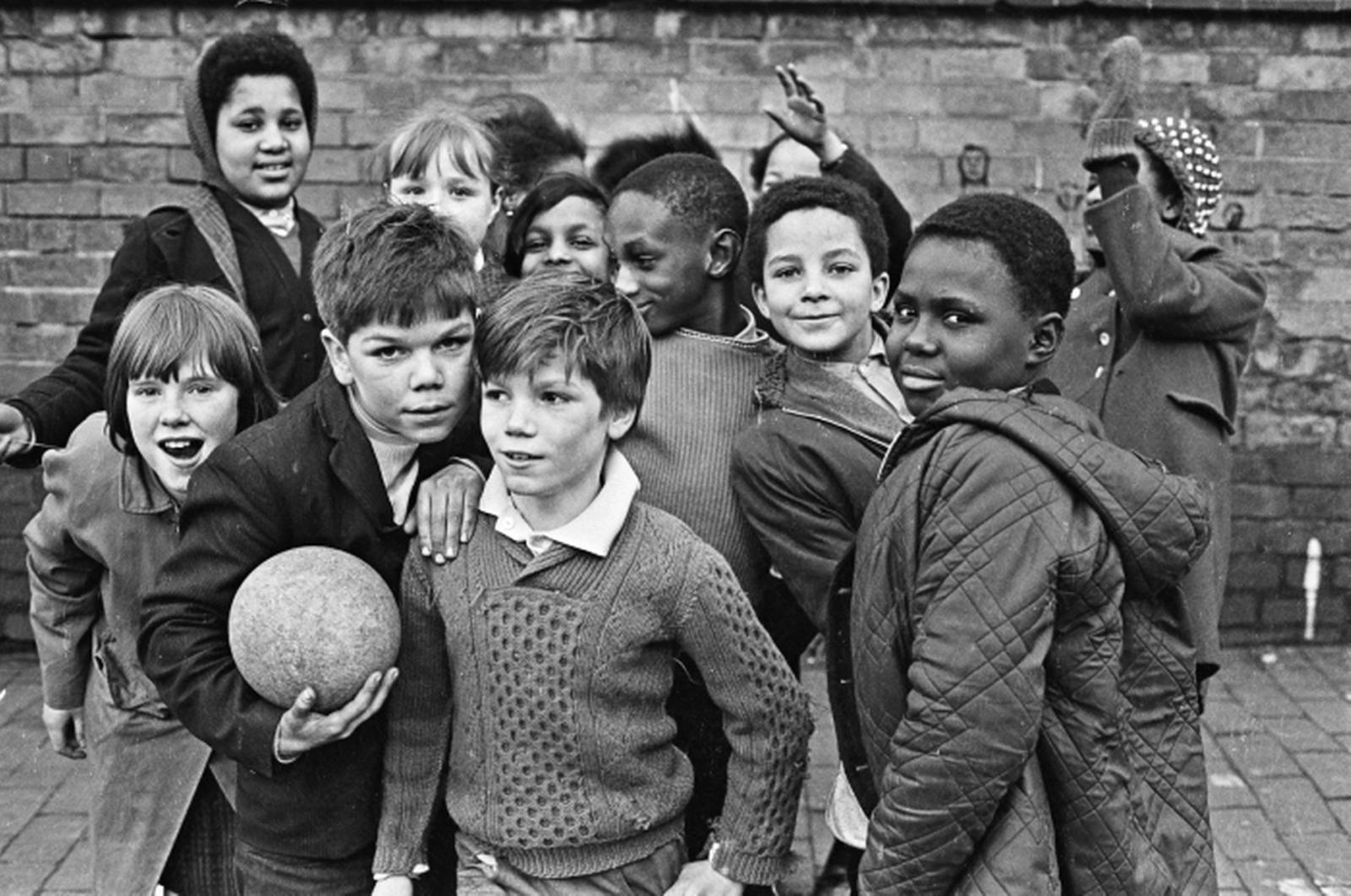

There is no better illustration of the need for a balanced view about racism in UK as suggested in the Report than the bizarre event, coincidentally on the same day of March 31, 2021 with the publication of the Report, at Pimlico Academy, a secondary school in Westminster, London which has a left leaning teaching staff. A quarter of the school’s 1200 pupils are of white British heritage, but the largest minority ethnic groups are black Caribbean and black African.

The new headmaster David Smith, educated at Oxford and LSE, is a traditionalist, interested in discipline, good conduct and achievement, and in implementing the motto of the Academy, libertas per cultum, freedom through education. The motto indicates cultivation and culture, not instilling propaganda.

Mr. Smith proposed some changes. Headscarves had to be black or navy blue, not colored. The rule would be that hair must be maintained in a conventional and understated style. Hair styles that hide the face or may block the views of others in class would not be permitted. A number of students said the new rules were racist, discriminating against those pupils with afros and hijabs.

On March 31, the students staged a walkout and a demonstration at the school, protesting against Smith’s proposals. Though there was no connection with this, the Union flag was torn down and burned, “there ain’t no black in the Union Jack.” Again, with no relevance to the school issue and hair styles, banners called for the end of racism, Islamophobia, transphobia, and for “change.” Later, the protestors complained of the school curriculum, focused they said on white kings and queens. They reprimanded the Academy for its lack of recognition of black history month and the BLM movement.

The demonstration was approved by NEU, the militant National Union of Teachers, a body which had blocked teachers from hosting live online lessons during lockdown. The NEU considered this an invasion of privacy. The protest was also supported by a Marxist group, the Socialist Workers Party, also engaged in another anti-government protest, Kill the Bill, a bill that would give police more power to curb protests and prevent disruption.

Most of the teaching staff at the Academy voted in favor of no confidence in the headmaster. Mr. Smith, humiliated and hounded. was chased down a corridor, pursued by a male student. The pressure was too strong for him. He backed down, apologized to staff and students, saying they were passionate about the things that matter to them, and agreeing that the right to protest is a civil liberty which all enjoy. He promised a review of the proposed hair style, and to review the flying of the Union flag again outside the Academy building.

The Commission might well comment. Hair today and hair tomorrow raises the volume on the pessimistic narratives about race.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link