Theater mask frescos – Pompeii

by G. Murphy Donovan (April 2022)

“History is moving pretty quickly these days, and the heroes and villains keep on changing parts.” – Ian Fleming

Professional literature is usually a bore; unless its fiction about a profession. Herein lies the rub. Most professionals are not that interesting. Nevertheless, the rare blend of professional and creative juices makes for unique cocktails. Fiction provides both opportunity and license for a kind candor that would be impossible in the confines of institutional or academic literature. Good fiction about institutions is a literary libation of sorts; providing a draught of insight, truth, and entertainment.

Writing about the Intelligence business, Ian Fleming and John le Carre are two of the best; Fleming a sordid stylist of fantasy and le Carre a gothic, if not morbid, realist. Both in their own ways do what the progenitor of English theater admonished all writers to do, hold a mirror up to life. In short, illuminate the humorous and dark sides of human intercourse. If nothing else, the Intelligence profession is a gold mine of comedy and tragedy. No writers have exploited those motherlodes better than Fleming and le Carre.

Ian Fleming

BONDAGE

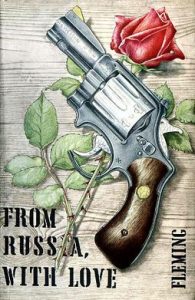

Ian Fleming might have been the author of a new literary genre; the autodidactic fantasy. If Fleming were a sketch artist today, he might write graphic novels. Ian spent a literary career developing a single cartoon character, James Bond; a homage to the Crown, patriotic spies, and all the rubbish that espionage fiction can freight.

Bond was at once; handsome, dashing, athletic, virile, former Naval Intelligence officer, who operated out of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) with, apparently, an unlimited expense account and every gadget and gizmo, real or imagined, known to mankind. In all Bond adventures, the hero invariably encounters and engages dangerous yet delicious women, ripe and willing.

Bond was at once; handsome, dashing, athletic, virile, former Naval Intelligence officer, who operated out of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) with, apparently, an unlimited expense account and every gadget and gizmo, real or imagined, known to mankind. In all Bond adventures, the hero invariably encounters and engages dangerous yet delicious women, ripe and willing.

Pussy Galore and Octopussy indeed.

Clearly, the Bond series is not just an autodidactic product, but also a kind of embellished serialized autobiography. Bond was the man Fleming used to be—patrician and genuine Intelligence officer, running real clandestine operations in WW II. Bond was Fleming’s comic alter ego too, closeted with a fetid imagination in sub-tropical Jamaica.

You could argue that Ian Fleming lived his fantasies.

The parallels between fictional Bond and the real Fleming are remarkable. Fleming drank too much, smoked too much, shagged a host of women, and died young. He began life as a failed cadet, getting expelled from Sandhurst with “the clap,” a persistent dose of gonorrhea. Seems as a schoolboy, Fleming was also called to answer for too much “oil” on his hair. Ian was a bit of a dandy or fop, often photographed with bow ties and a long elegant cigarette holder.

Alas, Fleming’s early salvation was good genes and prominent family. He was a trust fund baby serving in a war when the right school and social connections gave Naval commissions to the sons of privilege. If nothing else, Fleming captured the spirit of noblesse oblige. He repaid the British establishment in full with decades of bestselling propaganda for England, Western Intelligence in general, and the Secret Intelligence Service in particular.

Initially, the Bond series was received poorly by the fussy London literary establishment. All that changed after the White House released a list of JFK’s favorite authors and Fleming made the cut. With Jack Kennedy’s endorsement, Bond books and movies became a franchise, if not a moneymaking miracle that thrives to this day.

Besides a suite of life shortening picadilloes, Fleming the man, had a dark side. He wrote as the British Empire was in decline after WWII and didn’t hide his contempt for American parvenues. The villains in the Bond series were always vanquished by superior English heroes while in the real world, Soviet KGB agents penetrated and out played the British SIS and the American CIA in a Cold War, now hot war, that still abides.

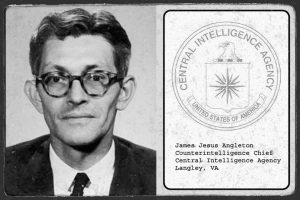

Despite all the sexual antics in the Bond books, Fleming also provided a player’s perspective on marriage in particular and women in general. Of marriage he said, “Most marriages don’t add two people together. They subtract one from the other.” On the ladies Fleming speculated, “All women love semi-rape. They love to be taken.” Out in the cold, the likes of Kim Philby (MI-6), James Jesus Angleton (CIA), and the Cambridge Five were screwing two superpowers.

Fleming might have been something of an autodidact too on the art of penetration. Sex is a major player in real and imagined Intelligence tradecraft. Of the Cambridge fab five; two were Ganymedes, one swung both ways, and the other two were metrosexual athletes. “Anything goes” is part of the Intelligence mystique.

Withal, Ian Fleming wrote wildly popular patriotic potboilers with tongue firmly in cheek, laughing all the way to the bank.

Smiley’s Lament

George Smiley is the everyman of espionage literature. John le Carré’s fictional Intelligence anti-hero, is a realpolitik counterpoint to Ian Fleming’s James Bond. “le Carré ” literally means “the square,” which, compared to Fleming, he was. David John Moore Cornwell used a pseudonym because he wrote as an active spook early in his literary career. Even the fictional “Smiley” was a pun. Like his creator, Smiley never had much to grin about with a personality range that ran from laconic to morose.

David John Moore Cornwel, aka John le Carré

And much like Fleming’s Bond, Cornwell’s Smiley was a reflection of the author. Le Carré was a veteran of both MI-6 (operations) and MI-5 (counterintelligence). Indeed, Cornwell’s cover was blown by a real-world mole, Kim Philby in 1964. Disgust with the incompetence of British and American Intelligence services colored Cornwell’s work and personal politics to the end. In life and literature Cornwell and Smiley were caustically anti-American.

It was more than a little ironic that, after Philby’s escape to Moscow, Cornwell threw so much shade on British and American politicians and spooks. Philby’s traitorous five made their bones on Cornwell’s MI-5 watch. Call it an irony of fives.

After Kim Philby’s defection to Russia, James Angleton, then CIA’s counterintelligence chief, claimed that he knew Philby was a spy all along. Angleton claimed that CIA had a mole too, like Mi-6’s sixth man.

James Jesus Angleton

Neither mole was ever unmasked or identified.

That ripe coincidence leaves history to speculate that Philby’s U/I conspirator and Angleton might have been one and the same man.

When the fictional Circus (SIS HQ) double agent is finally caught by Smiley in the early novel Tinker, Tailor, Smiley asks the traitor why he betrayed England. The mole replies: “I hate Americans, they think they can buy everything and anyone. Britain has become America’s streetwalker.” The jaundiced view of American arrogance reached some kind of apogee at the end of le Carré’s career with A Most Wanted Man (2008), possibly his best book and the finest screen adaptation of his work.

Le Carre’s last gasp provides a fictional analysis of the chasm between tactical competence and strategic failure. Or put another way, how America plays Whack-a-Mole with individual terrorists whilst Islamists succeed at the strategic level in places like Iran and Afghanistan.

The film version features Philip Seymour Hoffman (his last film too) as Gunther Bachman, a hapless Hamburg anti-terror agent. Robin Wright plays Bachman’s American counterpart. Clearly Bachman is a Smiley doppelganger; overweight, disheveled, cranky, and cynical. No small wonder that his American interlocutor, the Wright character, is an arrogant CIA bitch made to look and act like a female Nazi, complete with butch black bangs over one eye. Just as the trusting Backman roles up the Islamist financing network in Hamburg, American goons swoop in and “render” Bachman’s Islamist money man to only God-knows-where.

Role credits.

Le Carré’s work is a tribute to the prescience and power of metaphor. He pretty much invented much of the patois used in the working Intelligence world today, terms like “mole,” and “honey trap,” examples of life imitating art.

Back to the Cold (now hot) War

For le Carré, Americans had become the kind of German Nazis, or Russian Communists, that got him into the spy game in the first place. Before he died, le Carré relinquished his British citizenship. English reservations, and resentments, about America date to WWII, and a dependence of necessity. As the American star rose, the British sun set. The alliance became one where “special relationship” came to mean the London and Brussels were junior partners. London’s subordination to Washington was certified by the real-world Suez Crisis in 1956.

Steele

Fast forward to 2016 where we see another MI-6 (Russian desk) real-world operative, Christopher Steele, doing what Fleming and le Carre could only hope to do: run a successful “dezinformatsia,” or cut out, operation against a sitting American president. The SIS, MI-6, and Steele had long standing motives. Political novice Donald Trump just provided the opportunity.

IC Czars

The attempted insider coup in Washington was aided and abetted by a homegrown troika (espiocrats Clapper, Comey, and Brennan), America’s mirror image of the inept British SIS “Circus.” Ironically, Kim Philby, Britain’s most notorious mole, was an SIS advisor to James “Jesus” Angleton at Langley in CIA’s formative years. Philby and Angleton often did lunch in the basement of the Army Navy club on Farragut Square. While CIA and SIS ate bean soup on the taxpayer dime, hundreds of clandestine agents were slaughtered by the KGB on the altar of “allied” incompetence in the late 20th Century.

The 2016-2020 Beltway coup plot was embellished by a honey pot, Fiona Hill. Ms. Hill, was not just British and an ex-pat Russian specialist, but also a gal pal of Kit Steele, a Brookings (D) flack, and an anti-Trump mole at the National Security Council at the White House. Ms. Hill, no surprise, was also the star witness for the prosecution in Donald Trump’s star chamber trial.

Even bread crumbs do not overcome inertia at FBI and CIA counterintelligence these days.

Fiona

Just like the Angleton/Philby gordian knot, the American FBI was/is loath to pull on any of those loose threads that might ensnare or embarrass Steele, the Crown, or CIA in 2022. Recall that John Brennan, former czar at CIA, hand carried Steele’s dezinformatsiya dossier over to impeachment Democrats on Capitol Hill. If John le Carré were alive today, his next novel might be called, “The Dossier.” The American soap opera that began in 2016 is still playing to a stacked deck; another case of life imitating art, Falstaff doing Hamlet.

Angleton once called the theater of espionage a “wilderness of mirrors.” Indeed, Intelligence has more facets than mere fiction. With the deep state, nothing succeeds like excess. Espiocrats do what they do because they can.

Fiction is not just an escape; it is often a road that leads to the junction with candor. The intersection of fantasy and fact is often the only available crucible for truth these days.

__________________________________

G. Murphy Donovan is a former Intelligence officer who writes about the politics of national security.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

I feel as if every American citizen is cast into the role of counterintelligence agent nowadays.

Amen , Carl. When I was a youngster, I used to think that there were institutions that spoke truth to power in a democracy. In fact for years, I believed that Intelligence officers did just that . Unfortunately, candor is something more than a liability these days. Maybe it’s natural evolution. Good ideas create great institutions and then, inevitably, the institution becomes the enemy of ideas and ideals. We may have created a swamp today that’s too big to drain.