by James Como (December 2022)

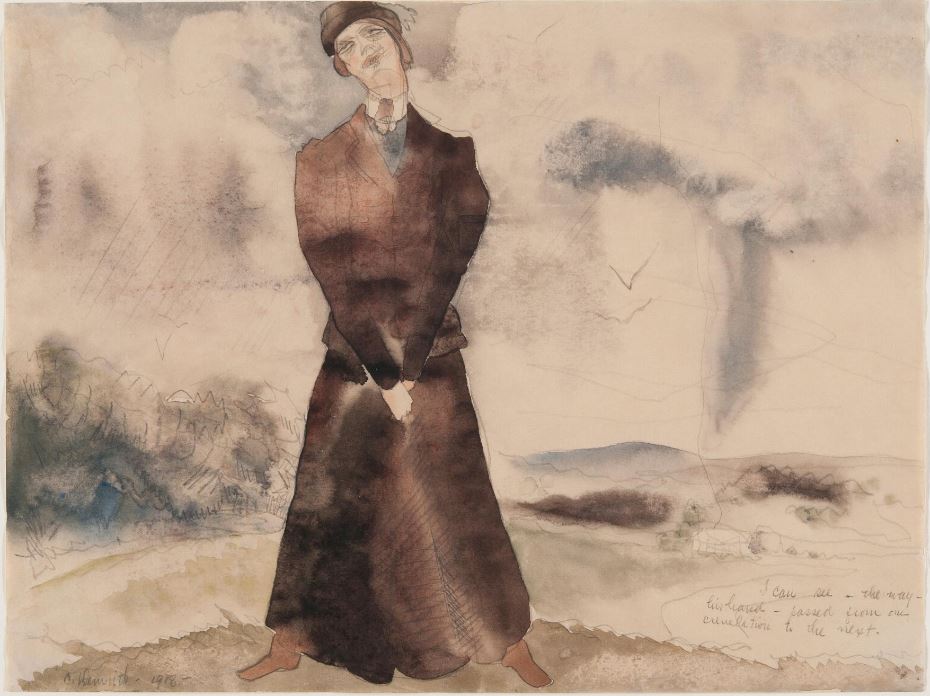

The Governess First Sees the Ghost of Peter Quint, Charles Demuth, 1918

Henry James remains the great explorer of our labyrinthine consciousness, moving within it as a cartographer even as he contends with its shapeshifting unreliability. No matter the attempts of philosophers somehow to explain away its non-material steadfastness, James is here, for the last century-and-a-half, to show us they are wrong, the tapestry of his art revealing an array of interwoven minds, because what continues to intrigue readers and critics alike is the very nub of that art, his rendering of the quakes and tics of mind.

James’ primary device lies in plain sight, and though subtle we’ve not known it for over a century; James himself has told us. Of course it is the Narrator, the consciousness that filters all others, although with James that consciousness is likely to be plural. By way of it—by way of them—vectors of allegiance, suspicion, hostility and self-doubt, as in a game of multi-dimensional chess, are poised and often pivoted one—or two or three—against another. And always they reveal the interanimates of self-image and reputation, with character rising and sinking below the surface of an exuberant (over-exuberant?) syntax.

The novels sustain the stance, but length mitigates the dazzle. The short stories restrain, and James perfectly appreciated the form (as in the ghost stories) for its limitations. In between, however, the novellas provide the exact amplitude that serves him best; in those we ambulate—not without a byway or three of minds muddling, hastening, frustrating, intriguing, fascinating and (maybe) clarifying—to a near horizon.

An ideal instance of this middle ground is Washington Square. There a wealthy and much-respected physician is worried over his plain and otherwise unremarkable daughter. Will she marry? That is unlikely, but, if she does, will it be to an honest man or to a gold-digging ne’er-do-well who has squandered his own boodle and knows she has ten thousand from her dead mother and much more to come from her father? The father’s widowed, live-in sister sides with the charming and handsome suitor, who leaches off his own sister, while the father, who is unambiguous and explicit in his disapproval of the suitor, draws a line in the sand: marry him and father’s money goes elsewhere.

And on it goes. The reader suspects the father is right and the daughter, who disavows her father’s accusations, wrong. The suitor, meanwhile, admits his past transgressions and allows that money is always something of an object in a marriage but denies being after only the brass ring. Meanwhile, on another front, he showers the daughter’s aunt, his devoted ally, with a handsome presence and much charm.

Father, daughter, suitor, aunt: the reader becomes a marble in a pinball machine, bouncing from one consciousness to another and another. Who is right about whose consciousness: the attributions of motive and actual ones, depths of passion, sincerity of devotion (the father may, after all, be merely experimenting), disinterestedness? The daughter, however, plays it, or (better) by the narrator is played, straight. She is utterly innocent even if decreasingly docile. So: can her goodness, honesty and logic assure us that her judgment is sound? Here James drops the curtain.

Our answer depends on whom we trust, trust being the gravamen almost everywhere in James. In fact, his main question is never not one of trust, just as in life off the page: trust in the neighbor down the hall, the doorman, this friend, that stranger, your mate? Whom should we, and the reader, believe? Who is narrating for whom? Exactly in that light have I referred to James’ narrators, which makes perfect, though not easily extracted, sense.

Those questions were treated dispositively (not to say exhaustively) sixty years ago by Wayne Booth in his A Rhetoric of Fiction (University of Chicago Press, 1961, 1983). There he tells us that “at the instant when James exclaims to himself, “‘here is my subject!’ a rhetorical aspect is contained within the conception.” And since there is no greater rhetorical propulsion than Aristotle’s ‘ethical proof,’ namely trust, Booth proceeds to untangle an array of trust-seeking narrators: the first person narrator, certainly, at varying depth of knowledge and intensity; the impersonal narrator, even one who may be silent; and (with many variations in between) the dramatized and undramatized narrator, whether self-conscious or omniscient.

And—ah! just here is the prize, for from that omniscience, or feigned omniscience, or self-referential omniscience, or reader-referential omniscience—from these emerges the Implied Author, the consciousness behind all artful consciousness, sometimes at one with the person who wrote the tale, sometimes not, but a consciousness whose presence the reader intuits.

This is the “author,” writes Booth, “who stands behind the scenes, whether as stage manager, as puppeteer, or as an indifferent God, silently paring his fingernails.”

In a novella like Daisy Miller, whose eponymous protagonist’s ambiguity is richly cultivated and who knows it, or in a novel like The Portrait of a Lady, whose great protagonist, Isabel Archer, “was better worth looking at than most works of art” but with whom “everyone tampers,” the imperious god pares away. Isabel’s consciousness is particularly painful to share, for “her errors and delusions were such as a biographer interested in preserving the dignity of his subject must shrink from specifying.” Brydon too, who in the ghost story “The Jolly Corner” is haunted—isn’t he? —by his own alter ego as he explores the house he grew up in, is as poignant as Isabel and Daisy, his consciousness either betraying him or betrayed by the Implied Author. We could go on, and on.

Which brings us to the tease that is The Figure in the Carpet. There the unnamed first-person narrator meets his favorite author and decides, compulsively, to discern the secret meaning in all his works, and I ask, could an Implied Author and Henry James be any closer? The plot is nearly adventitious; no secret, no figure, is ever revealed. Finally one asks (or at least I do): Is James poking fun at his critics or is he himself a sincere seeker after the philosopher’s stone of (fictional) art? The answer, I think, is, yes, sincere, but not only. There is much fun to be had, not least with critics.

After all, James was one, early on and busy, and a literary theorist too, his 1884 “Art of Fiction” from Longman’s Magazine revealing much about his call for the novel to “represent life.” He goes on to spin a compelling image. The writer’s sensibility, resembles a ‘huge spider-web of the finest silken threads suspended in the chamber of consciousness.” He attends to “the faintest hint of life” and is “one upon whom nothing is lost.”

Which is why he could not let go of two questions: what is the fundamental nature of literary art, and how must it engage minds interacting with other minds? Nurture matters, in many cases entire weltanschauungen matter, but nature—the involutions of a mind going beyond itself and thus into other minds—matters more. So: how to display that? Simple, really: include the reader in the web.

Booth reminds us that James claimed to “make his reader very much as he makes his characters.” In his “the Novels of George Eliot” James amplifies the idea. “When he makes him ill, that is, makes him indifferent, he does no work. When he makes him well … then the reader does quite half the labor.” That is, the reader becomes part of the weave, with the hope that nothing is lost on him. And that is act is enhanced if the reader grants James’ donneée, the writer’s subject. He must be granted that.

The epitome of this ‘making’ and granting—of the entanglement of the reader in the consciousness of the characters and thus being among those who may or may not be trusted—lies in our reading of the master’s great puzzle. Competing solutions to it still rage. But do not trust the author of The Turn of the Screw, for while you read his book, he reads you. Booth has expressed the conundrum aptly: “few of us feel happy with a situation in which we cannot decide whether the subject is two evil children as seen by a naïve but well-meaning governess (the first-person narrator) or two innocent children as seen by a hysterical, destructive governess.”

James exquisitely balances the evidence for each horn of the dilemma, and the cases for each have been so promiscuously rehearsed that one need note nothing beyond the precision of that balance. (Though here we might recall that Isabel Archer finally sees a ghost, but only after suffering and admitting her mistakes: she was not longer the “happy, innocent” person to whom ghost’s may not appear.)

In the event, Booth is right; vivid psychological realism works against our capacity for judgment—minds reading other minds. “Obviously, [James] could have made things clearer if he had wanted to.” But he did not. Rather he indulges his prevailing interest and so renders an ambiguity that makes demands on his readers, who, talking to and among themselves, in effect become additional narrators.

But might there be a figure in this carpet that undercuts the dilemma, a sort of pan-fiction meta-schema? And might James be telling us as much? After all, why does the story not begin at the beginning? We are told in a prologue that a group has gathered for Christmas and agreed to revive the tradition of the truly scary story. A certain Douglas has heard tell of such and, if he can retrieve the manuscript, will tell it true.

Along the way, if we pay close attention, we note four revealing items. First, everyone assumes each tale is true. Second, at five different places the narrator and others display a certain theatricality, a conscious effort to heighten the effect: “it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a tale should essentially be,” and there was “a rage of curiosity … [aroused] by the touches with which he [Douglas] had already worked us up … to a common thrill.” Third, on at least three occasions we are offered hints that the narrator of the prologue and Douglas are in cahoots, the latter directly addressing, as though cueing, the former so that the general effect is one of collaboration between the two. Last, at four different points in the prologue we encounter the implication that the governess (who claims the manuscript as her own) is herself the author.

And why not? In the story proper, the first-person narrator-governess twice shows an awareness that she is writing for an audience; at least twice she does what every omniscient narrator does: reads minds. She is self-conscious and once considers manipulation, and even her description of the house evinces her fertile imagination. Once she admits a taste for creative writing of all kinds. Her entire telling of the tale shows an intention to construct it, to heighten effect.

Finally, early on the reader is aware of the fact that the governess is recalling the episode, and so we ask: could she now not set the record straight? We know James would not. We recall what Booth has told us, adding to it: “At the very moment of initial conception, at the instant when James exclaims to himself ‘here is my subject!’ a rhetorical aspect is contained within the conception: the subject is thought of as … something that can be made into a communicated work. The subject? What subject? Why, nothing less than the machinations of story-telling itself, art as show-all. The magician announces his trick, his presumably irrelevant patter announces its trappings and techniques, and then he pulls it off. Be conscious, James is saying, not merely of how other minds are working, filtering, interpreting and re-telling the same tale, but of your own mind too, for it will trick you—and I know how to make it so.

Of a certain woman James tells us, “she had no airs and no arts; she never attempted to disguise her expectancy.” Is that a description of the daughter of Washington Square, who winds up a self-possessed spinster? Or of the governess, who ends her tale by holding a dead little boy? — m“ … alone with the quiet day.” Which is which? You may know that the woman without airs is the daughter, that the woman alone the governess, whose turn came eighteen years later. The Turn of the Screw is a puzzle, as well as a handbook for reading the master.

But there is one more twist. Douglas had called the inclusion of a second horrified child, a little girl, another “turn of the screw.” In the penultimate sentence of the Prologue, the narrator exclaims that he—or she—has a suitable title, this for a story not yet told. Then, very near the end of the tale proper it is the governess herself who provides it:

I could only get it at all by taking ‘nature’ into my confidence and my account, by treating my monstrous ordeal as a push in the direction unusual, of course, and unpleasant, but demanding, after all, for a fair front, only another turn of the screw (my emphasis).

The game is done. We, the readers, are those listeners within the fire-lit room—and the governess (reported as dead) the anonymous prologist speaking to us? As for the fictive world, we might suppose: Douglas is Miles, the presumably victimized little boy, who wrote the tale based upon an imaginative experience as a youngster; or the governess wrote the story—and actually lived it? —or gave it to Douglas (as he claims) when he was a boy who, grown, will tell it to thrill others as he was thrilled, or … It has been fun, navigating among these concentric worlds, the nail-parer at their center.

Nota bene: James never returns to the Prologue, does not finish it off, for that would utterly undo the screw. Far be it from him to solve his own puzzle, especially when he’s given us all we need.

Withal, what happens in that firelit room—nothing less than a playpen of consciousness that spins the web—makes for a very, very inside joke. If the reader gets it, he gets Henry James.

James Como’s new book is Mystical Perelandra: My Lifelong Reading of C. S. Lewis and His Favorite Book (Winged Lion Press).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link