by Robert Bruce (July 2019)

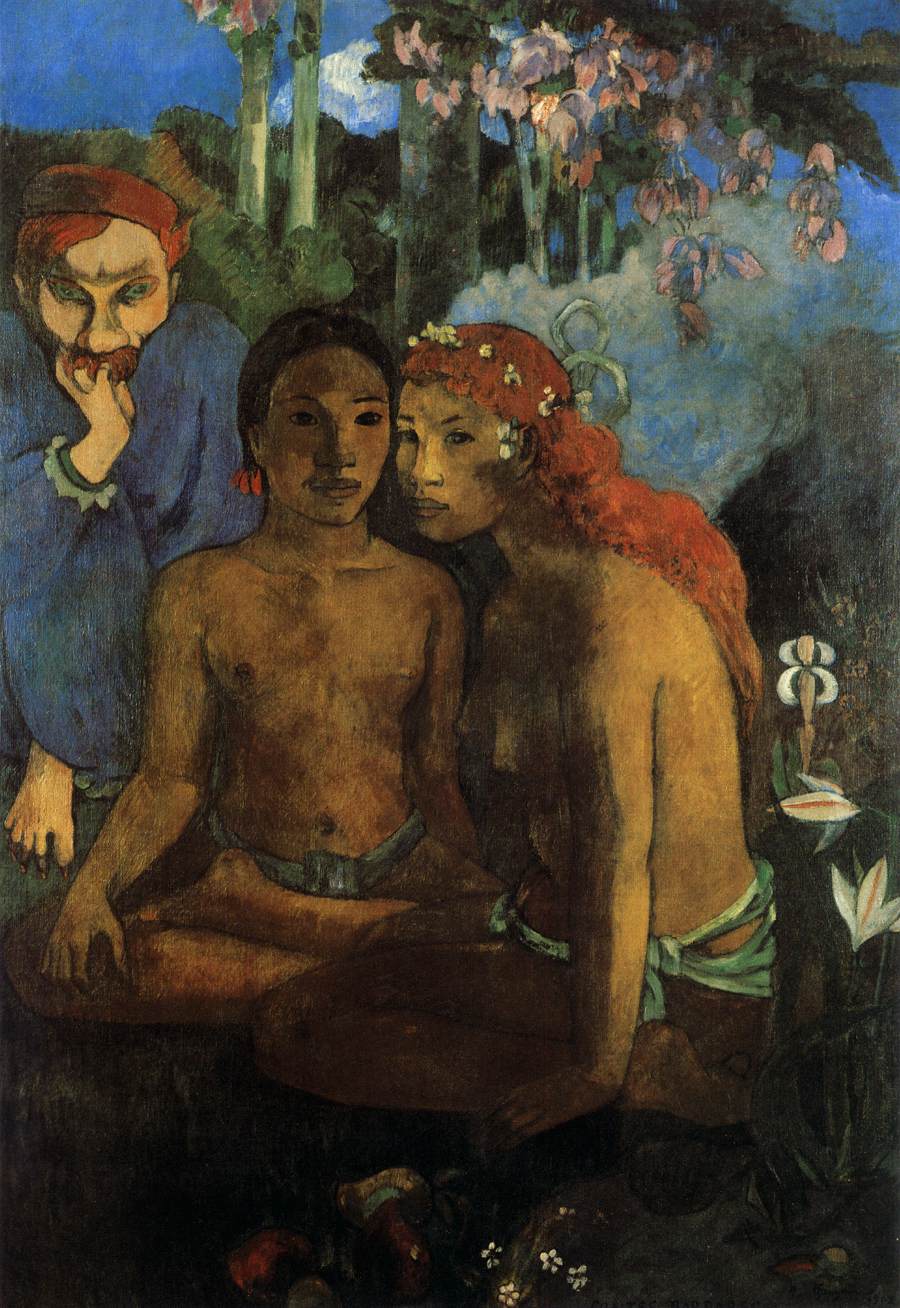

Contes Barbares, Paul Gauguin, 1902

As José Ortega y Gasset noted in a prescient diagnosis of twentieth century delusions, the most common pathology of Europe’s spiritual crisis was a reversion to the pagan idolatry of the tribe and when one looks at the serried ranks of frustrated hack writers and artists who beat a path to the Brown revolution, it is easy to see Nazism as the barbarian sequel to a disintegrating society. Thomas Carlyle doubtless would not have sympathised, but he was disillusioned enough with the soulless temper of 19th century utilitarianism to give one pagan relic a pass.

Thus Carlyle in his famous lecture on the Prophet:

What is the chief end of man here below? Mahomet has answered this question in a way that might put some of us to shame! He does not like a Bentham, a Paley, take Right and Wrong, and calculate the profit and loss, ultimate pleasure of the one and of the other; and summing all up by addition and subtraction into a net result, ask you, “Whether on the whole the Right does not preponderate considerably?” No, it is not better to do the one than the other; the one is to the other as life is to death,—as Heaven is to Hell. The one must in nowise be done the other in nowise left undone. You shall not measure them; they are incommensurable: the one is death eternal to a man, the other is life eternal. Benthamite Utility, virtue by Profit and Loss; reducing this God’s world to a dead brute Steam-engine, the infinite celestial Soul of Man to a kind of Hay balance for weighing hay and thistles on, pleasures and pains on:—If you ask me which gives, Mahomet or they, the beggarlier and falser view of Man and his Destinies in this Universe, I will answer, It is not Mahomet!

On the question of ultimate destinies, Carlyle merely had to pose the question to answer it and, if its jumble of incondite fragments held little intellectual appeal, its sheer earnestness was bound to appeal to an age destitute of faith but terrified of scepticism. Fanaticism, as Nietzsche noted, with what he termed ‘Carlylism’ very much in mind, is picturesque and, after the intrepid Richard Burton had given his flowery account of faux spiritual ecstasy at Mecca, he was to be joined by countless other Byronic heroes keen to use Arabs as a handy means of self-expression, not least soldiers like Glubb Pasha whose vision of the Arab ‘as every Englishman’s idea of nature’s gentleman’ hints at a revealing, if harmless prejudice.’ As Ernst Gellner noted, this is not so much a search for the noble savage as the search for a savage noble and it is as well to be clear on what this longing for restored rank and order was prepared to gloss over. When one gets past the obsessively homoerotic stylisations of Arabs and T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the only thing left over is an absurd sentimentalisation of a predatory herrenvolk with all the trappings such aristocracies of the blood one can expect and, lest anyone have any illusions on where this leads, the following observations on domestic husbandry of the Bedouin make sobering reading.

The gardens were entrusted to slaves, negroes like the grown lads who brought in the tray of dates to us, and whose thick limbs and plump shining bodies looked curiously out of place among the bird-like Arabs.

Lawrence explains that these healthy young blacks were originally from Africa, and had been brought as children to Arabia by their fathers on pilgrimage to Mecca, where they were afterwards sold.

Read more in New English Review:

• Slavery is Wrong, How Can Abortion be Right?

• From the Magical Land of Ellegoc to the First Man on the Moon

• We Will Not Go to Mars

“When grown strong they were worth from fifty to eighty pounds apiece and were looked after carefully as befitted their price.” Some of them became servants, Lawrence tells us,

but the majority were sent out to the palm villages . . . whose climate was too bad for Arab labour, but where they flourished and built themselves solid houses, and mated with women slaves, and did all the manual work of the holding.

The quotation from his famous Seven Pillars is entirely characteristic of the tone of the book, and one has to keep in mind this is written by a cultured man in 1928, not 1828, and it speaks to the spiritual malaise amongst the upper classes of this time that Lawrence was able to elevate all this covert homophilia, misogyny, and disdain of manual labour, as virtues. In the inter-war period, Arabism was to become something of a cult amongst the upper classes and, if for most, this misanthropy would have manifested itself in little more than the snobbery others might indulge in by converting to Catholicism, in shady individuals like St John Philby, who could rotate his loyalties effortlessly between Nazism and Wahhabism and the Soviet Union, we are clearly encountering a more deep rooted traison de clerks. For Philby, these were clearly emanations of a single misanthropic spirit and, if it is to be expected, bad men might choose Arab slavers and volkish blondes. More tender spirits were also at hand to anoint gentler primitives.

The ethnic candidates for this pocahontaisation are legion but, as any anthropologist will know, the heavy lifting was done by the Samoans, forever removed in the cultivated mind from their image as ferocious warrior kings and transformed into the promiscuous hippies of Margaret Mead’s fantastic work of fiction. Over the decades, Coming of Age—even amongst sympathetic audiences—has not worn well but, anyone who had got the measure of her formative intellectual influences, could have spared themselves the trouble of wading through her turgid fancies of the imagination.

Anthropology, before Mead set up stall in Columbia, was frequently the preserve of middle aged men in tweeds—as in the case of Malinowski employing the steady hand of science to firm up colonial rule. After she had escaped literary oblivion in Greenwich Village, all the routinised transgressions of the counter-culture were let loose on defenceless primitives, particularly when they provided a standing rebuke to bourgeoise civilisation. Thus, Mead who planned her trip to Melanesia with two things uppermost in her mind, ‘the influence of the progressive education movement’ and ‘a quick and partial interpretation of the first flush of success in Russia’ s educational experiments.’

It is hardly surprising she saw what she believed and, to judge by Derek Freeman’s meticulous dissection of her fieldwork, she didn’t spend much time looking, in any case. The bulk of her research was conducted up close and personal on a US naval base from whose lofty isolation her imagination roamed freely. The rest, as they say, is history. An ominous excerpt:

As the dawn begins to fall among the soft brown roofs and the slender palms stand out against a colourless gleaming sea, lovers slip home from trysts beneath the palm trees or in the shadow of the beached canoes, that the light may find each sleeper in his appointed place. Cocks, crow negligently.

Mead, like most of her ilk stewing in the risqué Freudian heresies of New England bohemia, saw repression all around her and Samoa, where all the local girls apparently consumed their free time in clandestine sexual adventures, provided an uplifting antidote to all the suffocating neuroses of well-bred westerners. Whether she actually saw any of the serial couplings she put to horrendous prose in Coming of Age is doubtful but, even if she had, there is a basic problem of chronology at the heart of her work. Samoa was held up as an uncorrupted idyll holding out against the Puritanism of modern western society but by the time Mead set out on her gap year, Polynesia had been subject to all the softening of manners a century of colonial les majestee and missionary activity had wrought, and Mead was pointedly dishonest in concealing this fact. As she conceded in a tiny and guilty footnote,

The new influences have drawn the teeth of the old culture. Cannibalism, war, blood revenge, the life and death power of the matai, the punishment of a man who broke a village edict by burning his house, cutting down his trees, killing his pig, and punishing his family, the cruel defloration ceremony, the custom of laying waste plantations on the way to a funeral, the enormous loss of life in making long voyages in small canoes, the discomfort due to widespread disease-all these have vanished.

Indeed they had, to which one must add three cheers for French and Yankee imperialism. No one moreover should have been surprised if it did open up some windows for casual sex. Mead’s sloppy Mills and Boon romance should have consigned her to academic oblivion in saner times but when anthropology departments expanded in the 60s, this florid fantasy turned the heads of a generation waiting patiently to be corrupted and the reasons are not difficult to locate. When Mead’s kindred free spirit Ruth Benedict penned her idyllic fantasy on the Amazonian Zuni, she pointedly noted they were a tribe ‘beyond good and evil,’ who had not emerged from Eden and taken upon themselves all the sins of modern men. As a manifesto for that overrated decade, it virtually wrote itself and there is something very poetic in the fact that Mead made her brave sallies from an armed outpost of western progress. As a metaphor for the carefree students acting out their violent ennui in a society made secure enough to afford these indulgences through the victories of better men, it is an apt one and posed few risks. As Taleb might say she had ‘no skin in the game’ and the errors simply compounded themselves. The flights of fancy you can embark on when you mock the uniforms that guard you whilst you sleep are endless, particularly when Marxists are so intent on inverting Marx’s most treasured dictum. In the 20th century, whatever the great man might have hoped, his neophytes were only concerned with interpreting (a much more important task than Marx’s arid materialism allowed for) the world and the drive to mine the past for utopia reached obsessive proportions. For anthropologist Marshall Sahlin, the acme of progress was the Stone Age and, if this voyeuristic primitivism petered out harmlessly in a bobo cult of didgeridoos, it nevertheless betrayed an infantilism of aspiration which is central to our current crisis.

Read more in New English Review:

• A Detransitioner’s Story

• BIble Champs of the Ring

• The Welfare State

At its core is a retreat from the hard trials of civilisation. To retreat into a world of thought crimes, ordered social ranks, and effortless mental tranquillity is comforting to the weak spirited, but the lack of moral effort leaves a gratuitous taint on the mind nonetheless. Anthropology, as Stanley Diamond notes, is the most alienated of professions—it draws as of necessity on gadflies less interested in the real virtues of exotic cultures than in the luxurious moral grandeur of guilt, and the cheap signalling it promotes has had disastrous effects on cultures which should have been left to die out. In New Zealand and Australia, customs which might have profitably been consigned to the dustbin of history have been given a new lease of life, and the grim harvests in terms of soaring alcoholism, illiteracy and bastardised identity politics are a testament to what happens when you try to be part modern. You can’t, any more than you can be half pregnant, but you can harvest picturesque cultures for tourist accessories whilst they implode, and this is a more insidious form of cultural imperialism than any 19th century missionary might have dreamt up and symptomatic of the inner heartlessness of liberated intellectuals.

From such intellectual dead-ends, thinking with your blood is no great leap: we are in the trendy Marxising jargon simply retreading the German debate of civilisation versus culture to a much wider audience and coming to much the same conclusions. As Sandall noted in his much-neglected classic The Culture Cult:

The myth of the Noble Savage was and is little but an illusion of the alienated urban mind. But many people prefer illusions. Humanity can only endure a little reality at a time.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

_____________________________________

Robert Bruce is a low ranking and over-credentialled functionary of the British welfare state.

More by Robert Bruce.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link