by Theodore Dalrymple (September 2021)

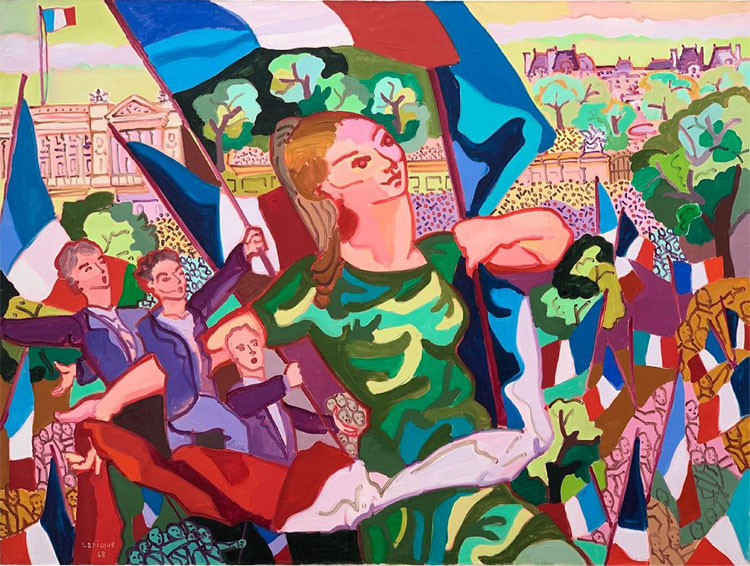

30 mai 1968, Charles Lapicque, 1968

Every ten years, in the eighth year of the decade, there is an outpouring of books commemorating the ‘events’ of 1968 in Paris. I hope to live see the sixtieth anniversary, though at my age I am less sanguine about the seventieth, and will by then probably have other things on my mind, if I still have one, such as putting my shoes and socks on.

In 2018, —true to form, the fiftieth anniversary making it a particularly evocative year—there were many books published, including one of photographs, titled Mai 68, l’envers du décor (May 68, the Other Side of the Scenery).

Why the other side of the scene? Normally, it is the supporters of and participants in the so-called revolution who attract the most attention; memoirists tend to congratulate themselves on the generosity of their own impulses at the time, even if they now acknowledge that the revolution wasn’t really a revolution at all, and that perhaps they were wanting in wisdom in certain respects. This book emphasises that, on the contrary, the events were not just a manifestation of youthful high spirits and supposed idealism, but often ugly and destructive.

I have come late to looking at pictures gathered into books to try to understand how things were. Perhaps it was intellectual snobbery on my part that inhibited me; I felt not that the camera lied, but that the selection of pictures lied. But words are just as highly selected and selective; and often pictures reveal things that words would not, because no one would think them worth recording. Often what is not remarked is, with the passage of time, as telling as what is remarked.

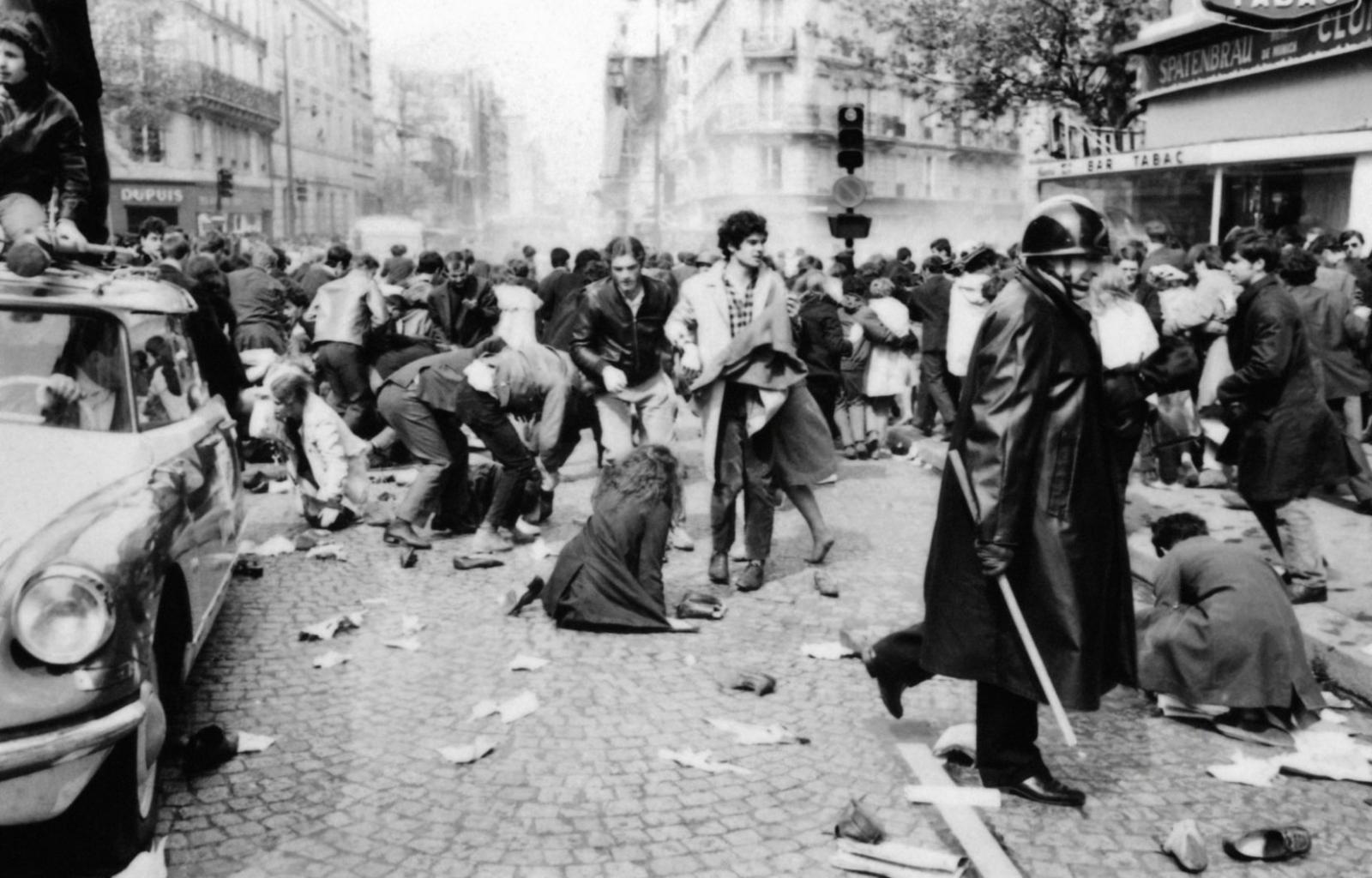

I doubt, for example, that anyone recorded in writing that, even during the demonstrations, a fair number of the students wore jackets and ties. As far as I could make out from the photographs, not a single one wore jeans. One or two even wore suits. As for their shoes, there were very few sneakers: many more wore slip-in suede shoes of considerable elegance. They were no proletarians or horny-handed son of labour. At the very least, they were dressed smart-casual.

Shoes, of course, used to be significant as clues to social status, at least in the days before the universal sneaker. I remember when I was last in South Africa, just after the un-banning of the African National Congress there; I met a high official of that organization at a party given by a wealthy businesswoman. Clearly, the manoeuvring for the coming political takeover had started (it was made possible by the downfall of the Soviet Union, which meant that an ANC government could not rely on subventions from that source for the implementation of socialist policies, and would therefore have to go in for kleptocracy and token redistributionism instead). The ANC man wore lizard-skin shoes that would have cost the GDP per head of the country at the time. They were shoes definitely not made for the veldt, the rough land around the city, or for the dusty townships, or even for a quick downpour. Beautifully fashioned, they were intended more for ornament than use. They were suitable more for attendance at a potentate’s durbar that for everyday life. Aha, I thought even at the time, so much for equality.

Not, of course, that the universal sneaker is completely without its social gradations: on the contrary, if you are alert to the fashions of the day in certain quarters, you can tell a lot about the hierarchical status of a person according to the brand and model that he wears, though to the untutored eye one looks very much the same as another. I once knew of a man who got into a fight and was murdered because his sneakers had been mocked as unfashionable or passé. I suppose this is an illustration of what Freud called the narcissism of small differences.

But to return to May, 68. The French riot police also wore ties at the time (as did the press photographers), and though they had a reputation for brutality they were singularly ill-equipped to deal with serious violence by comparison with their successors of today. They seem almost amateurish, as if nothing really serious could happen on the streets. They were much less disciplined than now, and perhaps their very lack of equipment or their failure to form proper ranks increased their violence rather than decreased it. Nevertheless, today in France, as everywhere else, the riot police look as if they have strayed from the set of a science fiction film. Protest and its suppression have become professionalised.

After the mess made by the young insurgents, real proletarians in overalls had to come out to clean up after them. There is a telling picture of six workers with buckets and ladders scraping the revolutionary posters from the walls; they are like servants of a class of people who do not clear up after themselves. In the courtyard of the Sorbonne, we see a large poster of a smiling Mao, in his theatrical prole costume (that no prole actually wore until ordered to) with the words ‘To serve the people’ in large letters beside it, though ‘The people to serve us’ would have been more appropriate.

A French communist leader of the time, Georges Marchais, who later became General Secretary of the party, was not an admirable man, perhaps, but he had a certain shrewdness. He spotted very early that the May, 68 ‘uprising’ was, in fact, a kind of frivolous upper-class party in which things are smashed for fun because they are so easily replaced (albeit at others’ expense), those doing the smashing never having had the common human experience of going without.

In general, it’s all about the sons of the upper bourgeoisie—who are contemptuous of students of working-class students—who will quickly lower their ‘revolutionary flame’ to the level of a night light in order to go and manage papa’s companies and exploit the workers in the best traditions of capitalism.

This, far more than most predictions by Marxists, turned out to be the case, disregarding the standard attack on capitalist exploitation. Many of the leaders of Mai, 68 became prominent businessmen and bureaucrats, sometimes both. They were indeed les fils de papa.

There is a splendid (by which I mean revealing) photograph of a platform of French communist leaders at a meeting during the events. They are all standing, no doubt to receive the applause or adulation of their followers. They are unsmiling, to say the least; in fact, they have, although French, precisely the visages of an East European Politburo of the period. Their faces seem to be made of concrete slabs; one would expect nothing but langue de bois to emerge from their mouths. They look as if they have spent much of their time in windowless rooms discussing the dialectics of ruthlessness, punctuated only by stodgy meals washed down with vodka and cigarettes. The only woman on the platform, on the extreme right of the photo, is about as feminine as a Soviet tractor-driver. The French Communist Party was the most Stalinist in western Europe and in fact had prepared secret lists of prominent people (hundreds or thousands of them) for incarceration or elimination after the Revolution. It regularly received about twenty-five per cent of the votes, and it had built a large headquarters in Paris, with a saucer-shaped concrete bunker in the front. It is astonishing that an organisation so shamelessly totalitarian in its aspirations should have attracted the loyalty of so many intellectuals who regarded the slightest constraint on their conduct as an intolerable trammel of their freedom.

The woman in the picture bears a resemblance to Elena Ceausescu, who also features in the book. General De Gaulle was on a state visit to Romania when the troubles broke out and we see both Ceausescus at the welcoming ceremony at Bucharest airport. (The picture of Elena with Madame De Gaulle in particular reminds me of what I had forgotten, namely that women of a certain social status still wore white gloves when in public, a custom now as remote from us as the divination of the future from chickens’ entrails.)

The Ceausescus are caught nearly at the beginning of the period of their pomp. This lasted from 1965 to the end of 1989. At the time of the photograph, meeting a world-historical figure, they had, of course, no intimation of their subsequent fate, death by firing squad after trial by a kangaroo court, but it is this very lack of such intimation that provokes the kind of reflections to be found in John Donne:

Variable therefore miserable, condition of man! this minute I was well, and am ill this minute. I am surprised with a sudden change, alteration to worse, and can impute it to no cause, nor call it by any name. We study health, and we deliberate on our meats, and drink, and air, and exercises, and we hew and we polish every stone that goes to that building: but in a minute a cannot batters all, overthrows all, demolishes all; a sickness unprevented for all our diligence, unsuspected for all our curiosity… summons us, seizes us, possesses us, destroys us in an instant.

For all our sophistication, this remains fundamentally our condition and perhaps will always do so (as I hope it will, for to know one’s fate with any exactitude, apart from that of death itself, would be an intolerable psychological burden). It might be, of course, that if the Ceausescus had known their fate, they would have accepted it with equanimity: a few final hours of ignominy and humiliation in return for nearly a quarter of a century of power and luxury—power being one of the greatest of all luxuries, beyond mere lavish meals in the midst of penury, and other such delights).

Looking at photographs, with their ability to freeze time for as long as they themselves last, brings a stab of pain, though not an entirely unhappy pain, to my heart. When, for example, I look at the picture of a handsome young man, with an intelligent and sensitive face, evidently a student aged about 20, a certain amount of blood streaming down one side of his face though not from a very serious wound, his upper arm gripped by a riot policeman as he arrests him, I feel that melancholy known by the name of nostalgia. The young man is dressed in a casual pullover as he might be today; he is indistinguishable from any such young man of the present day, he is indisputable modern in a way that a young man photographed fifty years earlier still would not be. He is still of an age when he thinks he will be young for ever, but now he must be seventy-three or four years of age, and the riot policeman arresting him probably about ten years older still, if he is still alive.

We are mostly so immersed in the drama of our present moment, which seems permanent to us, that we do not take Donne’s Devotions on Emergent Occasions to heart, and why on every reading they strike us anew. We cannot keep in our mind for very long the thought that our situation may become catastrophic at any moment, for such a thought, though obviously true, would paralyse us and can be indulged in from time to time as a corrective to pride of the Ceausescus’ kind.

What has become of the young men (mostly young men) who, following convention while believing themselves to be bravely defying it, marched down the boulevards shouting fatuous slogans, now that they are geriatrics? Are they proud or ashamed, or merely forgetful?

How much meaning there is to be sucked from the photographs! How surprising also little details are, for example that in 1968, at least in Paris, very few cars had wing mirrors. And that brings back an unimportant memory to me, that when people bought cars in those days wing mirrors were optional extras that added to the cost of the car. Strangely, to remember something so unimportant as this is a pleasure independent of its worth or significance. By a certain age reminiscence is an end in itself.

__________________________________

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Kenneth Francis) and Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link