by Theodore Dalrymple

“Virgin and Child” by Dierec Bouts circa 1455-1460.

Notwithstanding the recent disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we are still very fortunate by the standards of all previously existing human populations. Those, however, are not the standards by which we judge our own condition: instead, we compare it with some ideal normal, a perfection, which never has existed and never will exist.

This, perhaps, partially explains the extraordinary bitterness with which we approach our modern problems: any deviation from the perfection which is held to be the natural state of the world is not only magnified in our minds but assumed to result from someone’s wickedness.

“In the midst of life we are in death,” says the Book of Common Prayer; we might usefully change this nowadays to, “In the midst of privilege, we are in grievance.” I say privilege, incidentally, because we have done nothing to merit our good fortune: it was bequeathed to us by the efforts of our forerunners.

It is hardly news that misery is not necessarily proportional to the objective features of the world that cause it. All the same, I admit to having been startled by an advertisement I received over the internet for an exhibition called “Mother!,” now running in art gallery in Copenhagen.

I will overlook the installation of what looked to me like the amputated legs of pregnant mothers suffering from varicose veins after their pregnancies, hanging from the ceiling in a kind of forest, and remark only on the two paintings reproduced in the advertisement. The first, “Virgin and Child,” was by Dieric Bouts (circa 1400 to 1475), and the second, “Ginny and Elizabeth,” by Alice Neel (1900-1984).

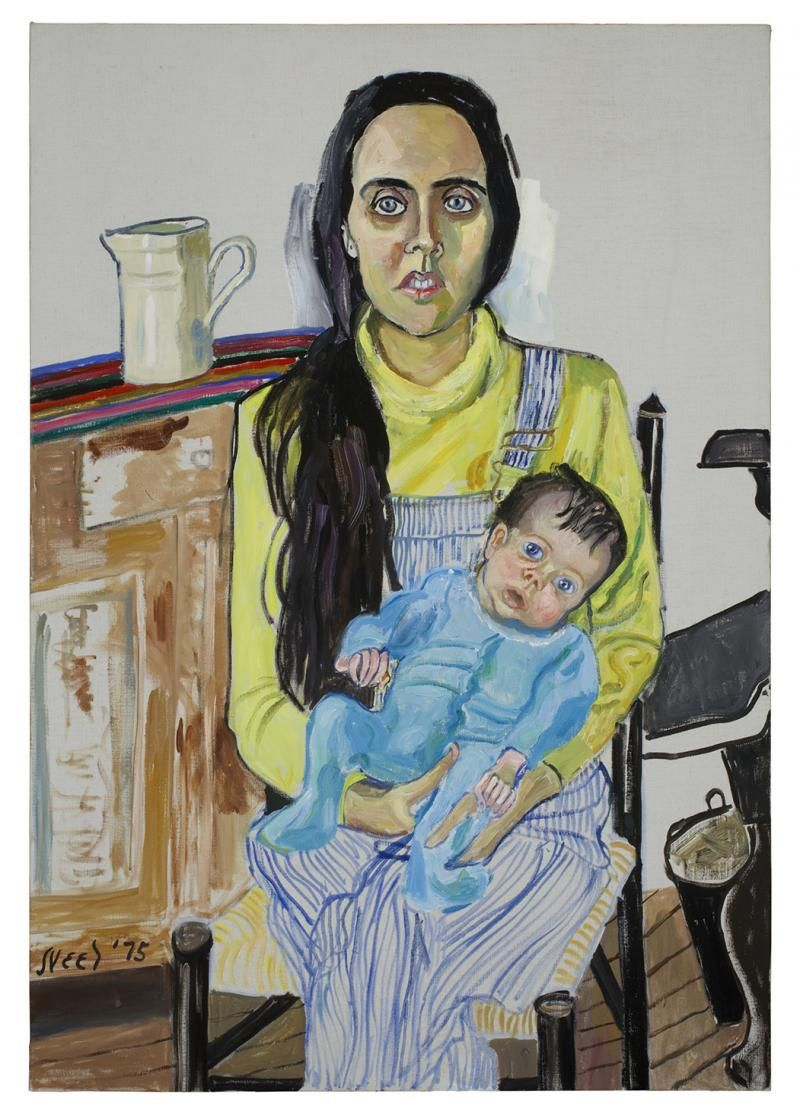

“Ginny and Elizabeth” by Alice Neel

“Objectively,” the half millennium that separated these two artists was one of enormous improvement from the point of view of average life chances and standard of living—despite the terrible wars and regimes that disfigured the history of the twentieth century.

By the time Neel came to paint her picture “Ginny and Elizabeth” (1975), moreover, the worst of the century was over.

In the time of Dieric Bouts, by contrast, life was routinely of an incredible hardship almost for everyone, and even the best-off were but an illness or minor injury way from the kind and degree of suffering almost unknown to us, with no possibility of relief, at least none of the medical variety.

To mention but one hardship relevant to the these of the exhibition: in Bouts’ century, probably about a twelfth of women died sooner or later in childbirth. By 1975, maternal mortality was a tiny fraction of what it had been, perhaps in the region of a thousandth of what it was in earlier times.

But Bouts’ picture is serene and tender, while that of Neel is so anxiety- ridden that it makes the observer feel deeply anxious. If one saw Ginny and Elizabeth in real life, one would be unsure whether one ought to call the doctor, the social worker or the police, in order to forestall a tragic denouement.

The mother in “Ginny and Elizabeth” looks at the end of her tether. The baby is not much better.

I am not criticizing Neel or saying that mothers such as she depicts (as she does also in other pictures) do not exist and therefore that her picture is unrealistic.

We are not in the regions of Hieronymus Bosch’s fevered imagination. There is no doubt, either, that her portrait is a powerful one in the expressionist mould: the mother is raddled by care and perhaps by illness, at the very least post-partum depression or psychosis.

Not surprisingly, the baby is not a happy smiling one of the type that reduces us all to cooing soppiness; on the contrary, it looks as if it might keep us awake all night and perpetually need changing. I have known several cases in my career as a doctor that ended with infanticide.

Perhaps Bouts chose to paint “Virgin and Child” so tenderly not only because it was religiously required to do so, but because his society had need of calming images that provided some respite from the harsh realities of daily live and common experience.

We often need, or think we need, the opposite of what we have: and it is not uncommon these days to read that it is the positive duty of the artist to unsettle, because otherwise we should descend into a tepid bath of complacency or worse.

And, pace COVID-19, our lives are so safe that we have a desire to feel that they are really no such thing, that we live constantly on a knife-edge of danger. Good fortune is less gratifying to us, psychologically, than bad.

I am not arguing for the prettification of art or that art should not deal with subjects that are disturbing. I do not think there can be prescribed or forbidden subjects for art.

Among the most moving pictures known to me are Velasquez’s portraits of dwarfs and a mentally handicapped boy in the Prado: they are a moral education in themselves, for Velasquez’s love of and respect for his subjects—which surely were not usual at the time—are, to me at least, evident. If these pictures disturb, they are also of transcendent beauty.

Many modern artists, especially those who achieve fame, go for the disturbing while bypassing the beautiful. This does not imply that they are without great talent: clearly no one would say that of, say Lucien Freud.

The very fact that they are talented is disturbing in itself, for they depict the world in a brilliantly cold light, as if the world were to them almost hateful, deprived of all tenderness and worthy only of exposure as cruel.

I don’t have an explanation for this. It seems to me that it is in some way defensive. Expressing tenderness or love renders you vulnerable, especially to mockery, as does declaring too openly what you consider beautiful.

A kind of aesthetic agnosticism or cynicism renders you, by contrast, invulnerable, because no one can know what you truly find beautiful.

You become like the kind of person who is always joking: in that way, you can never know what he really thinks. But aesthetic cynicism leaves the field of beauty open to those who do not, or cannot, rise above the level of kitsch. No wonder we are so good at ugliness.

First published in the Epoch Times.

4 Responses

Engaging and thought-provoking. So what does minimalism tell of our world as it turns its back to it, rejects it, renders content null and void? Minimalism is the visual arts equivalent of lobotomy, and many of us are attracted to it (that state of mindlessness), pay top dollar for it. Strange days have indeed found us.

The guiding principle in art now is emotion, not religious faith or awe. The idea is to depict strong feelings and to provoke the same.

Should not this article be expanded further? The key to solving the crisis in the West (Christendom) might well be found in this consideration of the tendency in the arts and entertainments towards misery guts fare. Never mind in art! For example, I have seen recent billboard advertising for a streaming media company in which the phrase “world-class entertainment” is emblazoned over it — and the images of three fantastically glum-looking actors (that’s one actor and two actresses) stare vacuously off at an angle or into the middle-distance (not at you: that would be too much).

Don’t we need to be consoled? As in given a steaming, sweet cup of tea and a lift from the travails of even modern life? Would not the symbolic bunch for “entertainment as we’ve never known it” be carried by a group photo of The Muppets, say, in all their unabashedly send-themselves-up glory! They were a radical bunch back in the day. Should not the imagery of grim and constantly mournful self-reflection as seen on TV in the pained expression of many an actor, in the internet era, be discarded for more of the light entertainment of yesteryear that dominated the few TV channels that were all there were as a favour to the many migrants to the West who are arriving from God-forsaken lands? Just as the streets of New York were alive with vaudeville, live music, Silent Era comedies, in other words a bit of cheer, for the latest arrivals to the New World more than a hundred years ago. Such was the craving before radio for art or entertainment that it all immediately fired the imagination of many of those immigrants (several of whom left their talented mark on the American arts-and-entertainments scene). What with the mush of terrible music in the public square today, the West finds easy ways to keep shooting itself in the foot. With such beat music all the rage, how harsh these latest sounds must be on the ears of the youngest children in society who go out to the shopping malls with their mum. The kids of the 70s had much nicer sounds bombarding their ears. Might not the newest migrants deserve to be treated to Elvis? Whose music they may be unaware of?

With the mountain of grim imagery and sound coming through hi-tech devices today, even The Muppets would have to set out to console (rather than tickle you pink). Things are that bad. But The Muppet Show is out there, you cry. At the touch of a button! But they, the Muppets, are in fact now well and surely in the hazy cultural background, on the far distant horizon — yet now accessible to you, and you alone, with the latest and greatest telescopes, they say. If you want to be anti-social too! But it’s not as if folk today are watching the latest grim box-sets in each other’s company: it’s each to his or her own device, even within a household. Yet everybody’s watching the latest “show” all the same. And as if to prove it, up go the posters for the fantastically glum-looking actors: to the fore they go, the antithesis of the Bollywood musical look! With so much real misery in India, no wonder there is a massive market for Bollywood musicals. In the old days of three miserable TV channels, it’s no wonder people looked up the TV Entertainment programme listings in the papers: they demanded something cheerful and light and could find it.

Movie poster after movie poster in the West shows a grim-stricken visage. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would be a tonic to alleviate this! And I’m pretty sure the immigrants (whom we would want to cheer up) love westerns. Now those old westerns, you know.

Grimness is easier to sell because we no longer have to watch TV in each other’s company. And maybe grimness sneaks in because no longer are two or three souls gathered in front of a television together. It used to be that the grander the screen, the grander the entertainment. And grander the audience for that cheery entertainment: so fostering a cheery community.

Now back to the article! Thank God, you say.

From the piece: “In the midst of life we are in death,” says the Book of Common Prayer; we might usefully change this nowadays to: “In the midst of privilege, we are in grievance.” Well, that privilege and that grievance were seen the other week in central London at anti-Israel protests by the assembly of a large group of well-dressed, healthy, robust individuals, in whose immediate forebears thirty years ago such characteristics would not have been so evident.

The painting “Ginny and Elizabeth” is by someone of a generation which was inclined to say in the late 20th century that “In my day, life was tough. Not like today.” I find this 1975 painting interesting and arresting. And it reminds me of the 19th century sketches of various characters that punctuated Dickens’s novels. The artist herself was born in 1900. Not knowing anything about her, her painting to me is almost a riposte to the image of the 1970s that those born after 1975 might have in their mind: an image based on garish fashion and groovy music. The consolatory things in the culture at that time (such as good solid songs) may be mistaken by today’s young generation as carefree good times had by all. Perhaps by the mid-1970s, the artist behind “Ginny and Elizabeth” knew to pay short shrift to the pretentiousness of “easy living” as evidenced by the plethora of adverts in colour. And that pretentiousness of the rising lower-middle class, say, was satirised sharply by the televised play “Abigail’s Party” in 1977.

Perhaps “Ginny and Elizabeth” represents one example of the push and pull between not what is beautiful and what is disturbing, but between what is complacent and what is gritty. Unfortunately, such worthwhile grittiness may be borrowed many years later to lump it in with other works in an exhibition that touts grimness and decay. It gets a different sheen. The late artist Beryl Cook’s colourful jovial, rotund characters in my mind are a riposte to the grittiness and cynicism of life. The irony is that such humour cannot be highlighted as a worthwhile endeavour in art because there is too much misery in the world. The world of the arts must then address this all-consuming misery as a priority. And so the tasks to do are to reflect that misery with more misery. To hold a mirror up to society. The longer that goes on, the more our relish for life through art gets chipped away at. What is bizarre is that over the last year, the left-leaning arts and entertainments have decried the shutting down of cultural and arts events as a result of the pandemic because it’s bad for the soul, bad for the mind. The arts are a vital part of health, the arts crowd says. Indeed! Yet folk who look to put on or produce what’s beautiful or humorous or witty might not get the plaudits they deserve because their work is out of touch with the trendy concerned consumers who apparently know what they want and need in terms of art or the arts. We’re all over the shop.

It’s as if it must be the West and the West alone that must save the world. And until it does so, nobody can elevate the beautiful or the witty into the cultural mainstream, as that’s just insensitive and the West showing off what can accrue from freedom and true artistic expression. So yes, in the midst of great privilege, the grievance show must go on!!

Dieric Bouts’ painting of Mother and Child must have been much more than a wonderful consolation to those who saw it and who could not read and write but who were Christians nevertheless. To whom and how many was this painting available to see in the 1400s? Art ought to be a way to experience a saving grace. And a saving grace offers consolation in spades and even much joy.

Should not this article be expanded further? The key to solving the crisis in the West (Christendom) might well be found in this consideration of the tendency in the arts and entertainments towards misery guts fare. Never mind in art! For example, I have seen recent billboard advertising for a streaming media company in which the phrase “world-class entertainment” is emblazoned over it — and the images of three fantastically glum-looking actors (that’s one actor and two actresses) stare vacuously off at an angle or into the middle-distance (not at you: that would be too much).

Don’t we need to be consoled? As in given a steaming, sweet cup of tea and a lift from the travails of even modern life? Would not the symbolic bunch for “entertainment as we’ve never known it” be carried by a group photo of The Muppets, say, in all their unabashedly send-themselves-up glory! They were a radical bunch back in the day. Should not the imagery of grim and constantly mournful self-reflection as seen on TV in the pained expression of many an actor, in the internet era, be discarded for more of the light entertainment of yesteryear that dominated the few TV channels that were all there were as a favour to the many migrants to the West who are arriving from God-forsaken lands? Just as the streets of New York were alive with vaudeville, live music, Silent Era comedies, in other words a bit of cheer, for the latest arrivals to the New World more than a hundred years ago. Such was the craving before radio for art or entertainment that it all immediately fired the imagination of many of those immigrants (several of whom left their talented mark on the American arts-and-entertainments scene). What with the mush of terrible music in the public square today, the West finds easy ways to keep shooting itself in the foot. With such beat music all the rage, how harsh these latest sounds must be on the ears of the youngest children in society who go out to the shopping malls with their mum. The kids of the 70s had much nicer sounds bombarding their ears. Might not the newest migrants deserve to be treated to Elvis? Whose music they may be unaware of?

With the mountain of grim imagery and sound coming through hi-tech devices today, even The Muppets would have to set out to console (rather than tickle you pink). Things are that bad. But The Muppet Show is out there, you cry. At the touch of a button! But they, the Muppets, are in fact now well and surely in the hazy cultural background, on the far distant horizon — yet now accessible to you, and you alone, with the latest and greatest telescopes, they say. If you want to be anti-social too! But it’s not as if folk today are watching the latest grim box-sets in each other’s company: it’s each to his or her own device, even within a household. Yet everybody’s watching the latest “show” all the same. And as if to prove it, up go the posters for the fantastically glum-looking actors: to the fore they go, the antithesis of the Bollywood musical look! With so much real misery in India, no wonder there is a massive market for Bollywood musicals. In the old days of three miserable TV channels, it’s no wonder people looked up the TV Entertainment programme listings in the papers: they demanded something cheerful and light and could find it.

Movie poster after movie poster in the West shows a grim-stricken visage. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would be a tonic to alleviate this! And I’m pretty sure the immigrants (whom we would want to cheer up) love westerns. Now those old westerns, you know.

Grimness is easier to sell because we no longer have to watch TV in each other’s company. And maybe grimness sneaks in because no longer are two or three souls gathered in front of a television together. It used to be that the grander the screen, the grander the entertainment. And grander the audience for that cheery entertainment: so fostering a cheery community.

Now back to the article! Thank God, you say.

From the piece: “In the midst of life we are in death,” says the Book of Common Prayer; we might usefully change this nowadays to: “In the midst of privilege, we are in grievance.” Well, that privilege and that grievance were seen the other week in central London at anti-Israel protests by the assembly of a large group of well-dressed, healthy, robust individuals, in whose immediate forebears thirty years ago such characteristics would not have been so evident.

The painting “Ginny and Elizabeth” is by someone of a generation which was inclined to say in the late 20th century that “In my day, life was tough. Not like today.” I find this 1975 painting interesting and arresting. And it reminds me of the 19th century sketches of various characters that punctuated Dickens’s novels. The artist herself was born in 1900. Not knowing anything about her, her painting to me is almost a riposte to the image of the 1970s that those born after 1975 might have in their mind: an image based on garish fashion and groovy music. The consolatory things in the culture at that time (such as good solid songs) may be mistaken by today’s young generation as carefree good times had by all. Perhaps by the mid-1970s, the artist behind “Ginny and Elizabeth” knew to pay short shrift to the pretentiousness of “easy living” as evidenced by the plethora of adverts in colour. And that pretentiousness of the rising lower-middle class, say, was satirised sharply by the televised play “Abigail’s Party” in 1977.

Perhaps “Ginny and Elizabeth” represents one example of the push and pull between not what is beautiful and what is disturbing, but between what is complacent and what is gritty. Unfortunately, such worthwhile grittiness may be borrowed many years later to lump it in with other works in an exhibition that touts grimness and decay. It gets a different sheen. The late artist Beryl Cook’s colourful jovial, rotund characters in my mind are a riposte to the grittiness and cynicism of life. The irony is that such humour cannot be highlighted as a worthwhile endeavour in art because there is too much misery in the world. The world of the arts must then address this all-consuming misery as a priority. And so the tasks to do are to reflect that misery with more misery. To hold a mirror up to society. The longer that goes on, the more our relish for life through art gets chipped away at. What is bizarre is that over the last year, the left-leaning arts and entertainments have decried the shutting down of cultural and arts events as a result of the pandemic because it’s bad for the soul, bad for the mind. The arts are a vital part of health, the arts crowd says. Indeed! Yet folk who look to put on or produce what’s beautiful or humorous or witty might not get the plaudits they deserve because their work is out of touch with the trendy concerned consumers who apparently know what they want and need in terms of art or the arts. We’re all over the shop.

It’s as if it must be the West and the West alone that must save the world. And until it does so, nobody can elevate the beautiful or the witty into the cultural mainstream, as that’s just insensitive and the West showing off what can accrue from freedom and true artistic expression. So yes, in the midst of great privilege, the grievance show must go on!!

Dieric Bouts’ painting of Mother and Child must have been much more than a wonderful consolation to those who saw it and who could not read and write but who were Christians nevertheless. To whom and how many was this painting available to see in the 1400s? Art ought to be a way to experience a saving grace. And a saving grace offers consolation in spades and even much joy.